There are many things I like about my gig on the SoundStage! Network, but what I enjoy most are my colleagues. They all share my passion for music and audio, and they’re all very knowledgeable. And they have strong opinions that often diverge in interesting ways.

Take spatial audio, for example. “Spatial audio” is a term that streaming services use for surround music encoded in Dolby Atmos. Amazon Music Unlimited and Tidal began offering Atmos-encoded music in 2020; Apple Music followed suit in 2021. Some of my SoundStage! colleagues are fans; others are skeptics.

Jason Thorpe is a fan. During the High End show in Munich back in May, Jason heard an Atmos mix of the Who’s “Baba O’Riley” played on a €300,000 system built around PMC studio monitors. “I’ve seen the Who live, and I’ve heard them play ‘Baba O’Riley’ live,” he wrote in his show coverage on SoundStage! Global, “and I have to tell you, it wasn’t as good as listening to it on this PMC system.”

Jason Thorpe immersed in PMC

Jason Thorpe immersed in PMC

Geoffrey Morrison, our headphone guy, thinks spatial audio is a gimmick. In a recent review on SoundStage! Solo, Geoff noted that the Beats Solo 4 headphones will automatically play Atmos content from Apple Music when they’re paired with an iPhone, then added, “to me [this] is as interesting as 3D TVs weren’t.”

Like a true Canadian, I’m on the fence. I subscribe to Apple Music so I can listen to music in spatial audio through my iPhone 14 and Apple AirPods Pro (2nd generation) earphones—partly so I can write about the spatial audio, but also because I enjoy it. However, all of my out-loud listening is in two-channel audio, through the KEF LS60 Wireless active speaker system in my living room and the PSB Alpha iQ system in my home office. That’s not because I’m uninterested in surround sound. There’s just not enough space in our 1920s urban rowhouse for a full-blown Atmos system.

And I have some lingering questions about spatial audio. There’s a growing catalog of Atmos-encoded music on Apple Music, Amazon Music Unlimited, and Tidal—not just newly recorded albums, but remastered versions of classic albums from the 1960s onwards. But how many people are actually listening to this stuff? How are they listening? Through headphones? In Atmos home theaters? On soundbars? Do they appreciate the difference between stereo and Atmos? Do they enjoy it?

No one’s saying—and certainly not Apple. I reached out to Apple Canada’s PR department to arrange an interview for this piece, and got no response.

Inside the bubble

As it turns out, I’m not the only person asking these questions. Kevin Annocque would also like some answers—more about that in a later section.

Annocque is cofounder and general manager of Ensoul Records, a small record label based in Montreal, Canada. He’s also the manager of Dominique Fils-Aimé, one of the label’s artists.

Annocque began picking up some buzz about Atmos back in 2020 while Fils-Aimé’s third album, Three Little Words, was in production, and began talking about it with Jacques Roy, Fils-Aimé’s producer. By that time, Fils-Aimé had laid down some of the tracks for her fourth album, Our Roots Run Deep. Annocque and Roy discussed the possibility of mixing the album in Atmos with her.

Kevin Annocque

Kevin Annocque

“From the moment Kevin explained Atmos to me, I felt that it made perfect sense,” Fils-Aimé recounted in a SoundStage! Encore video about the album. “It absolutely aligned with the vision, the goals.” For her songs, Fils-Aimé often records hundreds of vocal tracks harmonizing with and supporting the lead vocals. “The goal of my music is to create this bubble that you’re immersed in,” she said. “Atmos allows that.”

The album’s last track, “Feeling Like a Plant,” includes three Congolese drums, which the production team recorded with 11 microphones. “That way, we would get way more tracks per drum,” Annocque told me during a Zoom call in mid-August. “We tried to create this drum circle with just those three drums. Because of all the microphones, we had all the tracks.” In the Atmos version, it was possible to place the drum tracks in different locations around and above the listener. “Their frequencies are very similar,” Annocque elaborated, “but they were spatially laid out so that you could distinguish them as separate instruments.”

Learning curve

To enable the project, Les Studios Opus, the Quebec facility where Fils-Aimé has been recording since 2017, installed a 7.1.4 Atmos system built around Focal ST6 studio monitors. Installing the system and calibrating the room took about six months, Annocque told me. Then came a learning period during which Fils-Aimé, Annocque, and Roy settled on an aesthetic for the Atmos mix and confronted some technical challenges.

With Les Studios Opus’s Logic Pro digital audio workstation, Fils-Aimé, Annocque, and Roy could listen out loud to their Atmos mixes through the Focal speakers, but they could also listen to binaural versions intended for headphone users.

Dominique Fils-Aimé at Les Studios Opus

Dominique Fils-Aimé at Les Studios Opus

With binaural rendering, the playback device performs a two-channel mixdown of the Atmos track, but with some DSP trickery. The renderer filters sounds differently depending on their location, mimicking the way our heads and outer ears filter sounds in the real world. We use these cues to determine the direction a sound is coming from. With Logic Pro, mastering engineers can use the standard Dolby binaural renderer or Apple’s binaural renderer. With the latter, they can preview how the Atmos mix will sound when played through headphones on an iPhone.

It was vital for the Atmos mix of Our Roots Run Deep to sound right when played through either renderer. “We want to have a compromise between the person who is lucky enough to have a full Atmos system and the end user who will be listening through earphones,” Annocque said, “because 95 percent of people will be listening to these masters in binaural. Binaural technology is progressing, but it’s not where the native surround environment is.”

It took a lot of trial and error to get the Atmos mix and the binaural mixdown right—and also a lot of help from other sound engineers who have worked with Atmos. The key was getting the lead vocals and other essential elements firmly anchored in the front by assigning them to the left, center, and right (LCR) channels. Other sounds were treated as 3D objects that could be placed all around the listener. But if they placed bass sounds above the listener, so that they would be played through the height-effects speakers in a full Atmos system, those sounds would almost disappear when the mix was rendered for headphone listening. “I remember with some of the first mixes, there was a major gap between the Atmos mix and the binaural render, and we had to do something about this,” Annocque explained. “I don’t know how many mixes per song we did, because we tried so many different things.”

The Atmos mixing studio at Les Studios Opus

The Atmos mixing studio at Les Studios Opus

Even at the last minute, there were unexpected wrinkles. Ensoul Records had delivered stereo and Atmos mixes to the streaming services, but when they streamed some of the tracks on the album in Atmos and listened through earphones, Fils-Aimé’s lead vocals in the front center sounded weirdly separated from the instrumental mix. Annocque called Justin Gray, a Toronto-based mix and mastering engineer who’s very experienced with Atmos, and Gray fixed the tracks. Ensoul then sent the revamped masters to the streaming services, and all was good.

When Fils-Aimé heard the Atmos mix, “she was in awe,” Annocque said. “She had goosebumps. She had ideas about building on certain things that she heard for the next album. Listening to the album in Atmos was triggering ideas about the creative inception of new songs where she could build from that experience.”

Listening through earphones

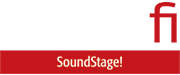

For this article, I created a playlist of spatial audio tracks on Apple Music and a playlist of stereo versions of the same tracks on Qobuz. For my first round of listening, I played these tracks through my iPhone 14 and AirPods Pro earphones.

With Apple Music’s Atmos mix of “Feeling Like a Plant” from Our Roots Run Deep, the Congolese drums were arrayed in a 180-degree arc just in front of me. I didn’t quite get a sense of the drum circle that Annocque had told me to expect—it was more like a semicircle just outside of my head, but impressive nonetheless. Fils-Aimé’s lead vocals were just in front of me, in the center, and like the drums, her layered vocals were spread out across the front. But there was never a sense of sounds coming from above or behind me.

Streaming the stereo mix from Qobuz, Fils-Aimé’s voice was inside my head, and the drums seemed to come from hard left and right, with the layered vocals spread from left to right inside my head. But her voice sounded a little fuller and more embodied on the Qobuz mix. And despite being sent to the AirPods via compressed Bluetooth, Qobuz’s 24-bit/88.2kHz stream sounded a little smoother than Apple’s compressed Dolby Digital Plus stream. I enjoyed both versions, but ultimately I liked the Atmos mix more. Not only did it more clearly separate the different elements of this song, it integrated them more effectively into a complete performance.

Next up was “Diversity” by the German keyboardist/composer Hauschka (a.k.a. Volker Bertelmann) from his latest album, Philanthropy. As with “Feeling Like a Plant,” Apple’s compressed Dolby Digital Plus stream was a tad harder-sounding than Qobuz’s hi-rez stream. But with Apple’s spatial audio mix, the sound was more outside my head, and the disparate elements were more clearly arrayed in an arc around the front. With Qobuz’s stereo mix, the sound was in the middle of my head and on the hard left and right. The deep, pounding synth notes hit a little harder on Apple’s Atmos mix.

In a feature interview published on Simplifi in December 2022, veteran UK mix engineer Heff Moraes cited Gregory Porter’s rendition of “Mona Lisa,” from his 2017 album Nat “King” Cole & Me, as a great Atmos mix. “It has huge dynamic range,” said Moraes, who is now business development manager for PMC Speakers. “I’ve seen people moved to tears when hearing it.” He later added, “What that track is doing is placing you in an immersive space in the middle of the orchestra.”

True to Moraes’s description, on Apple Music’s Atmos mix, the orchestra wrapped right around me, extending back a little beyond my shoulders. There was some front-to-back layering, but of course not as much as you’d get with a well-set-up speaker system—stereo or surround. Porter’s voice was beautifully presented right in the center of my forehead. But the orchestra did not extend very far into the center. Most striking was the incredible dynamic range, exactly as Moraes described it. On the 24/96 FLAC stream from Qobuz, the presentation was more two-dimensional and also dynamically more compressed. The big orchestral climaxes didn’t swell up the way they did on Apple’s Atmos mix.

At the bar

As noted, I don’t have a multi-speaker Atmos system in my home, but I do have an Atmos-capable soundbar, Bowers & Wilkins’s Panorama 3, which is connected to the Samsung 50″ Frame TV in my basement family room. So for some out-loud listening, I cued up my Atmos playlist in the Frame TV’s Apple Music app, and I compared the sound with Qobuz’s stereo versions, which I streamed to the B&W bar via AirPlay.

I started with the title track of Our Roots Run Deep. On the stereo mix from Qobuz, the soundstage did not extend beyond the dimensions of the soundbar itself. With Apple Music’s Atmos mix, the lead vocals were in the center, right under the TV screen. But the layered vocals extended far out to the sides—some sounds seemed to come from the far sides of the room—about eight feet from my left and right shoulders as I sat on a small sofa against the opposite wall. This made it far easier to appreciate Fils-Aimé’s creative arrangements.

Next up was an Atmos mix of “Exodus” by Bob Marley and the Wailers, from their 1984 compilation Legend (Deluxe Edition). Again, Apple’s Atmos mix was more immersive than Qobuz’s stereo mix. With the stereo mix, the soundstage was confined to the soundbar itself. On Apple’s Atmos mix, the background singers and brass instruments were above the soundbar and extended a few feet out to the sides. On the stereo mix, the bass-drum kicks and bass guitar hit a little harder—they were a bit fainter on the Atmos mix. However, Marley’s voice sounded more muffled on the stereo mix.

The passenger seat

When I interviewed Heff Moraes in late 2022, he spoke of having heard Atmos audio systems installed in luxury cars from Tesla and Volvo. “Both experiences were extraordinary,” he stated.

I wanted to experience this for myself, so I reached out to a couple of luxury car makers. Mercedes-Benz responded with a great offer. If I’d mission out to their Canadian headquarters in Mississauga, Ontario, they’d demonstrate three Atmos systems, all of them engineered by Burmester in Germany, in three different Mercedes-Benz models. I sat in the passenger seat while Mike Maduro, national manager of product management for Mercedes-Benz Canada, operated the controls and cued up tunes from the playlist I had sent the previous week.

The least expensive of the three cars was an E 350 sedan, at $73,900 (all prices CAD), plus $1100 for the upgrade to the Burmester 4D Surround Sound System. This system has 15 amplifier channels rated at 730W total, powering 17 speakers. There are also four “exciters” underneath the seats to add a tactile experience. I found the exciters distracting, so turned them down; otherwise, I really liked what I heard. On “Exodus,” Aston “Family Man” Barrett’s Fender Jazz bass sounded immensely powerful, but also well controlled. The guitars and horns came from the sides and back, while Marley’s voice was anchored in the front. Compared to Apple Music’s Atmos mix, the stereo mix sounded two-dimensional and slightly muffled.

The Burmester Surround Sound System, a 15-channel, 15-speaker system with amplifiers that deliver a combined 710W, is standard on the electrically powered Mercedes-AMG EQE SUV ($128,900). On “Feeling Like a Plant,” Dominique Fils-Aimé’s lead vocal was locked above the dash, while the layered vocals and multi-miked Congolese drums wrapped all around the cabin, creating the drum-circle experience that the producers intended.

Inside the Mercedes-AMG GT 63 S E Performance four-door coupe ($214,500) was a Burmester High End Surround Sound System, a $7020 upgrade. That system has 25 amplifier channels with a total output of 1450W and 25 speakers, including a sealed subwoofer and height-effects speakers in the headliner. This system produced the huge dynamic swings of the orchestra on Gregory Porter’s rendition of “Mona Lisa” effortlessly. And the orchestra wrapped right around the cabin, creating a truly immersive experience.

All three systems sounded glorious. It would have been interesting to play more two-channel music through them, because I think that’s how they’ll be used most of the time. But the immersive listening experiences they provided with Atmos tracks were amazing.

Luxury goods

I bought a new car late last year. My new VW Taos Highline has a premium Beats Audio two-channel system with six speakers plus a subwoofer. I’m very happy with the sound, but it doesn’t come close to any of the Burmester systems I heard at Mercedes-Benz Canada. The price doesn’t come close either. The Highline is the top trim level for the Taos in Canada, but it’s $35,000 cheaper than the E-class sedan with the upgraded Burmester 4D Surround Sound System, which was the least expensive vehicle in the lineup Mercedes-Benz showed me.

Right now, Atmos sound systems are available only from a few luxury car brands, but these represent a small part of the automotive market.

Of course, the ideal way to experience Atmos-encoded music is through an Atmos-capable surround-sound system. For a November 2021 feature on Simplifi, Vince Hanada listened to Atmos music through his home-theater system, which comprises an Anthem MRX 720 A/V receiver, Definitive Technology speakers for the front and surround channels, Angstrom ceiling-mounted speakers for the height-effects channels, and a Paradigm subwoofer. Overall, Vince liked what he heard. “It’s great to see new artists and producers taking up this medium,” he wrote, “not only to enhance stereo reproduction, but also to come up with new and creative uses for the extra speakers available in the formats.”

But home-theater setups like Vince’s are a comparative rarity—a luxury, to be honest. And most people use these systems for movies—they don’t consider the possibility of using them for music.

What’s playing?

As Annocque noted in our Zoom call, most people will be listening to spatial audio through headphones. But just because Apple Music, Amazon, or Tidal offer an album in Dolby Atmos, there’s no guarantee listeners will be hearing the Atmos version when they play it through their headphones.

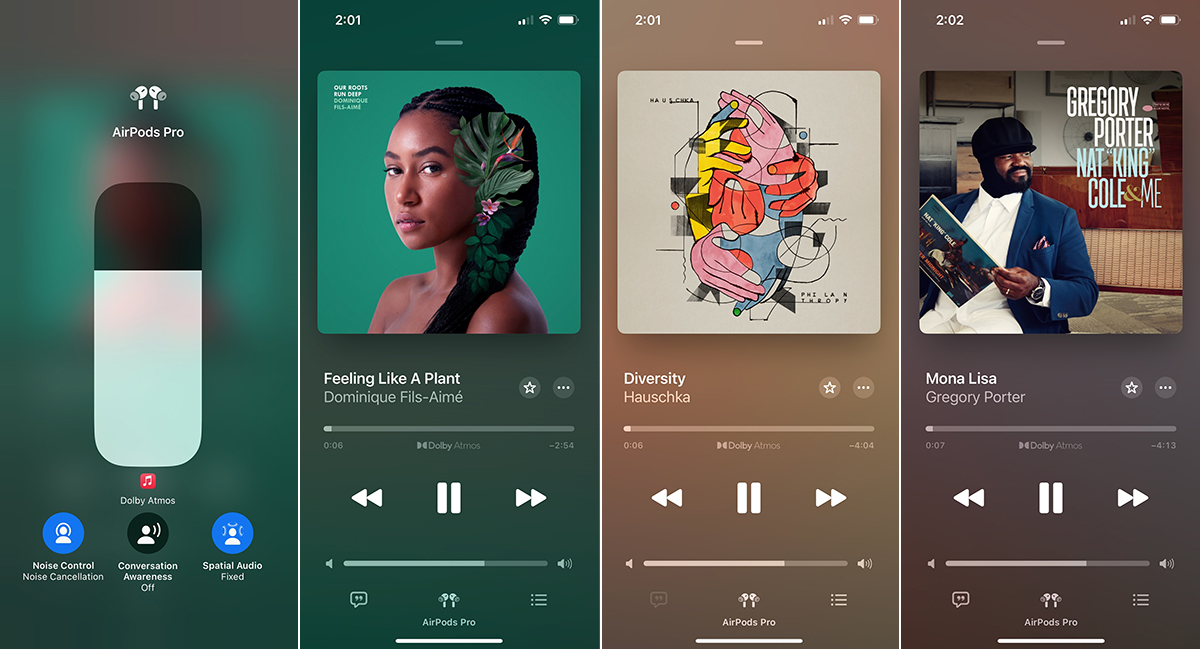

With my iPhone and AirPods, Apple Music will automatically stream the Atmos version of a track if it’s available. The iPhone will also switch to Atmos automatically with selected Beats headphones. But with most headphones, you have to enable Dolby Atmos in the Apple Music section of iOS’s Settings app. There are three options: Automatic, Always On, and Off.

With the Automatic setting, when I connected an AudioQuest DragonFly Cobalt and NAD Viso HP50 headphones to my iPhone and played the title track of Our Roots Run Deep, the Now Playing screen did not indicate whether the phone was streaming the Atmos or stereo version. If I selected Always On in the Settings app, the screen showed the Atmos logo. If I selected Off, it showed the Hi-Res Lossless logo. Interestingly, the differences between the Atmos and lossless streams were less pronounced than they were through my AirPods.

Who’s listening?

These considerations have led Annocque to ask the same questions I posed at the beginning of this piece: How many people are actually listening to spatial audio? And do they appreciate what they’re hearing?

On the artist portals for Apple Music, Amazon Music Unlimited, and Tidal, content providers can get statistics on number of streams, number of playlists, and listener demographics. But none of these services differentiate between Atmos and stereo streams.

“It’s very frustrating,” Annocque stated. “Apple Music has been pushing for this, and we actually got in on a Dolby Atmos playlist on Apple. I got the stream count for the playlist specifically. In Apple Music for Artists, which is basically their portal, there is no differentiation between the streams in stereo and the streams in spatial audio. I feel like we should get that information because we don’t know.”

Dominique Fils-Aimé’s first four albums

Dominique Fils-Aimé’s first four albums

Annocque hasn’t raised the issue with Amazon or Tidal. “I spoke with Apple, and they said that it’s a great point and they will look into it. I don’t know if it will be addressed. I guess it may be when the numbers speak and it’s a bigger volume.”

Annocque also wonders about user awareness of spatial audio and Dolby Atmos. “It feels like a lot of people are actually listening in binaural, in Dolby,” he said, “yet they don’t know it’s not stereo.”

This hasn’t dampened his appreciation about the creative possibilities of Dolby Atmos for musicians. “This is not a fad. I don’t think it’s going to go away anytime soon.”

My take

I’ve enjoyed every listening experience I’ve had with Atmos-encoded music from Apple and Tidal (I haven’t tried it with Amazon). But in my introduction, I said I was “on the fence” about spatial audio. Why?

Several reasons. The two best ways to enjoy spatial audio—a full-blown Atmos home theater and an Atmos-capable car-audio system—are luxury purchases for almost all people. An Atmos home theater is also impractical in many homes. But there are some very capable Atmos soundbar systems available, some with separate surround speakers and subwoofers—unlike the B&W Panorama 3 bar in my basement. These can make out-loud Atmos music more attainable for more households.

But as noted repeatedly in this piece, spatial audio is mainly a headphone thing, and here we come up against another issue: the effectiveness of the binaural renderers that are used for mixing Atmos audio down to two channels. I know that it’s possible to get more immersive experiences than I’ve had with my iPhone and AirPods.

Ensoul Records cofounders Fabien Rousseau and Kevin Annocque with Dominique Fils-Aimé

Ensoul Records cofounders Fabien Rousseau and Kevin Annocque with Dominique Fils-Aimé

How do I know? Because I’ve had them. At various audio shows, I’ve listened through Stax electrostatic headphones to true binaural recordings made with microphones placed in dummy heads. These recordings were literally transporting—they totally replicated the spatial characteristics of the recording venue.

I’ve also heard a binaural mixdown of an Atmos recording in a Canadian TV studio, and it too was mind-blowing. But that mixdown was done with Dolby Labs’ renderer, not Apple’s. Admittedly, I was hearing it through a high-end setup: a Sennheiser HDVD 800 headphone amplifier driving a pair of Sennheiser HD 800 headphones. But the presentation was completely outside my head. It was far more convincing spatially than anything I’ve heard from Apple Music.

All of this makes me confident that Atmos-encoded music “is not going away anytime soon,” per Annocque’s prediction. But will it become a mainstream thing? Will it ever become as ubiquitous as two-channel music? I’m not so sure about that.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse