On May 28, 2020, Tidal announced that it was rolling out Dolby Atmos Music for home-theater systems. Nearly a full year later, on May 17, 2021, Apple Music announced that, along with lossless audio, its catalog would support spatial audio, which also uses Dolby Atmos. For Tidal, Dolby Atmos Music is included in the higher-tier HiFi subscription at $19.99 (all prices in USD) per month for a single subscription ($29.99 for up to five additional family members). For Apple Music, spatial audio and lossless audio are included in the $9.99 plan ($14.99 per month for up to five additional family members). For most audiophiles, the biggest draw would be lossless audio—the company was joining niche providers such as Tidal and Qobuz, but Apple’s pervasive influence brings it to a much wider audience.

However, as an audiophile who’s interested in both home theater and audio, I was more intrigued by the Dolby Atmos format for music, having had a Dolby Atmos system in my listening room for watching movies for some time. I’ve always been interested in the way that surround sound can enhance the experience of listening to music compared with the ubiquitous stereo audio. Dolby Atmos is another variant of surround music, which the music industry has been trying to promote for many years. Sadly, none of the other formats have lasted—will Dolby Atmos be any different?

A brief history of surround music

Before I dive into Dolby Atmos for music, let’s take a look at how we got to spatial audio.

Back in the 1960s, quadraphonic sound was introduced in various media, such as open-reel tape and 8-track cartridge. In the 1970s, the format came to LP records in the form of SQ Quadraphonic. This format had mild success but eventually died in the late 1970s, and it’s easy to see why—for vinyl, quad sound required a decoder, and two extra amps and speakers. This was a sizeable investment for a niche format.

The next foray into surround music was after the Compact Disc (CD) was introduced in 1982. Although not officially supported, quadraphonic sound was present on some early CD releases, with a number of discs using original quadraphonic masters. These CDs weren’t true quad, with the surround signals folded down into the stereo mix, but they could produce some spatial effects through quad decoders. In 1991, QSound was released on CD. This format worked within the stereo realm of the CD, but phase manipulation was encoded in the mixing stage of CD production to provide interesting surround effects. One QSound CD I owned was Roger Waters’s Amused to Death (Columbia Records 4687612), and if I sat directly between my speakers, I could hear amazing sounds well away from the speaker locations. On the track “Too Much Rope,” a horse-drawn carriage moves from left to right, but in the middle of the room. The problem with QSound was that it was fussy with speaker positioning, and you couldn’t move your head around or the illusion was lost. Incidentally, you can find Amused to Death on Apple Music with these phase effects largely intact, so you can hear them for yourself even if you don’t have the QSound CD.

Once home theater became mainstream in the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a proliferation of surround-sound music formats on DVD, SACD, DTS CD, and DVD-Audio. All formats offered five main channels (left, center, right, surround left and surround right) and a subwoofer channel. Incidentally, DTS CD could have even more channels; the DTS-ES format could be decoded by a supporting DTS decoder to provide a sixth or seventh surround back channel. Progressing from DTS CD to DVD-Audio, the resolution increased as the years went by—from the lossy compression of DTS to 5.1 channels of high-resolution, 24-bit/96kHz music with the DVD-Audio format. My favorite format of the era is SACD. One great example of surround sound on SACD is Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s Long Walk to Freedom (SACD, Heads Up International HUSA 9109). When listening to “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes,” you can hear Melissa Etheridge’s vocals from the center speaker, with the group’s singers playfully harmonizing in the left and right surround speakers.

The latest surround format for physical media is High Fidelity Pure Audio, which was released on Blu-ray by the Universal Music Group in 2013. This format comprises up to 16 audio channels at a maximum resolution of 24/192, but losslessly compresses the channels through the Dolby TrueHD or DTS-HD Master Audio codecs. Like the other surround formats, High Fidelity Pure Audio never really took off.

Dolby Atmos for home theater

This brings us to Dolby Atmos. Dolby Laboratories first released Dolby Atmos in 2012 for the animated film Brave. Dolby Atmos for film uses up to 128 audio tracks and metadata to map precisely where sound “objects” are located. It then uses the theater’s speaker layout to play back these sounds in the theater in real time. While conventional surround sound is mixed to specific speaker locations, Dolby Atmos sound objects are mixed to a three-dimensional point in the theater space. This allows the sound designer much more precision for the placement of sounds.

Dolby Atmos for home theaters works in much the same way, but with fewer speaker locations—the maximum number of speakers supported is actually 24 floor speakers and ten overhead speakers, but most decoders support seven floor speakers and four overhead speakers, with output for one or two subwoofers. The first Blu-ray to feature a Dolby Atmos soundtrack was Transformers: Age of Extinction (2014). After that release, it took a while for a catalog of Dolby Atmos titles to build, since the releases on Blu-ray were few and far between. Having upgraded to a full 7.1.4 (seven floor speakers, one subwoofer, and four overhead speakers) Dolby Atmos system, I was resigned to it being a niche format (once again). But once 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray was introduced, there were many more titles with Dolby Atmos, or its rival format, DTS:X.

Dolby Atmos seems to have taken off in the home-theater realm through video streaming services. All of the major services, such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Apple TV+, and Disney+, have many titles in Dolby Atmos. For streaming video, Dolby Atmos is delivered through the low-resolution Dolby Digital Plus surround format (with a bitrate one-tenth that of Dolby Atmos on Blu-ray). Even with the lower resolution, I still find that Dolby Atmos greatly enhances movies and shows, for some titles, on these services.

Spatial audio and Dolby Atmos for streaming music

Apple’s spatial audio and Tidal’s Dolby Atmos Music use the same Dolby Atmos Music format to deliver immersive music through your audio system. Tidal and Apple Music don’t publish the bitrates of their services, but they are based on the Dolby Atmos Music format, which specifies a bitrate of up to 768kbps, using the Dolby Digital Plus codec. For comparison, CD quality (16/44.1) from Tidal is 1411kbps and Master Quality is up to 9216kbps (although the actual streaming bitrate is much lower).

To get Dolby Atmos Music in your home, you need a compatible Dolby Atmos decoder. This can be in the form of a home-theater receiver or an Atmos-enabled soundbar. You’ll also need a number of speakers, although those will be built into the soundbar if you go that route. I recommend at least a 5.1.4 system: five floor speakers, four ceiling speakers, and one subwoofer. I recommend four ceiling speakers because I find that the spatial immersion is not as effective with only two. If you can’t mount speakers on, in, or near your ceiling, you can use Atmos-enabled speakers that sit on top of your floor speakers and fire upward. The sound bounces off your ceiling to simulate ceiling-mounted speakers.

My Dolby Atmos setup is built around an Anthem MRX 720 A/V receiver, with a Definitive Technology speaker system for the floor speakers—BP8060ST main speakers, CS8060HD center speaker, ProMonitor 1000 surround speakers, and Mythos Gems for the two surround back speakers. The ceiling speakers are from Angstrom Loudspeakers—two Ambienti ceiling-mounted speakers and two Suono 100SD speakers mounted high on my front wall. Rounding out the system, I have a Paradigm Servo-15 V2 subwoofer for the low-frequency effects (LFE) channel.

To receive Apple spatial audio in your home audio system, you need an Apple TV 4K streaming device, either the original 4K device or the second-generation 2021 model. I picked up the 32GB 2021 version ($179). The Apple Music app is preloaded on the Apple TV 4K. To enable Atmos playback, choose Music in the Apps menu, select Dolby Atmos, and set it to Automatic. If the Apple TV is connected to a HomePod speaker or an audio system with Dolby Atmos, it will send out a Dolby Atmos stream.

Tidal is compatible with the Apple TV 4K streaming device, but you need to download the Tidal app from the Apple App Store. It’s also available for Amazon’s Fire TV—Fire TV Stick 4K, Fire TV Stick (3rd Gen) 2017, Fire TV Cube (1st Gen or 2nd Gen)—and Nvidia Shield TV or TV Pro (2019 or later) media streamers. All of these devices connect to the HDMI port of your home-theater receiver or processor, and to the internet either by Wi-Fi or through an Ethernet cable.

Listening to Dolby Atmos Music

Both Apple Music and Tidal have categories for spatial audio and Dolby Atmos but they don’t show all the tracks available. Finding additional Dolby Atmos tracks or albums on Tidal is a bit frustrating—for some albums, not all of the tracks are available in Dolby Atmos, and you can’t tell if they are Atmos-encoded until you start playing them. The easiest way I have found is to look online for user-created lists of Dolby Atmos tracks, and then use the search function in Tidal or Apple Music. Inputting search terms with the device’s remote by scrolling through the alphabet on the screen is tedious, but with Apple TV 4K and other voice-activated devices you can just push the handy microphone button on the Apple TV remote and speak your search terms. If you have an iPad and it’s set up to use the same Apple ID as the Apple TV 4K, you can also swipe down from the iPad’s top-right corner and find the remote icon. Then you can just type your search info into the iPad remote window. Another thing I found when listening to these tracks in both the Tidal and Apple Music apps is that either my system settings or the Dolby Atmos tracks had the volume of the surround speakers a bit too high—I had to lower the levels about 5dB so that I could hear the front speakers better.

There are two schools of thought on spatial audio—one view is from a traditional two-channel audio perspective, where it can be used to enhance the stereo listening experience. The other view is looking at spatial audio as a new medium, and using the extra speakers aggressively.

For the enhanced stereo perspective, the main objective is to create a realistic illusion of the performers in front of you. That’s been one of the goals of high-end audio since the beginning—can this system, with these two speakers, make me believe there are musicians here in my room? Spatial audio has the potential to greatly enhance the stereo effect by using a combination of all the speakers in a surround system for better sound placement. In a Rolling Stone magazine interview, record producer Giles Martin, son of Sir George Martin, summed it up best when talking about the Beatles remixes for spatial audio, saying, “I feel immersive audio should be an expansion of the stereo field, in a way. I like the idea of a vinyl record melting and you’re falling into it. That’s the analogy I like to use. And if you have lots and lots of things all around you all the time, it can get slightly irritating and confusing, depending on what the music is.”

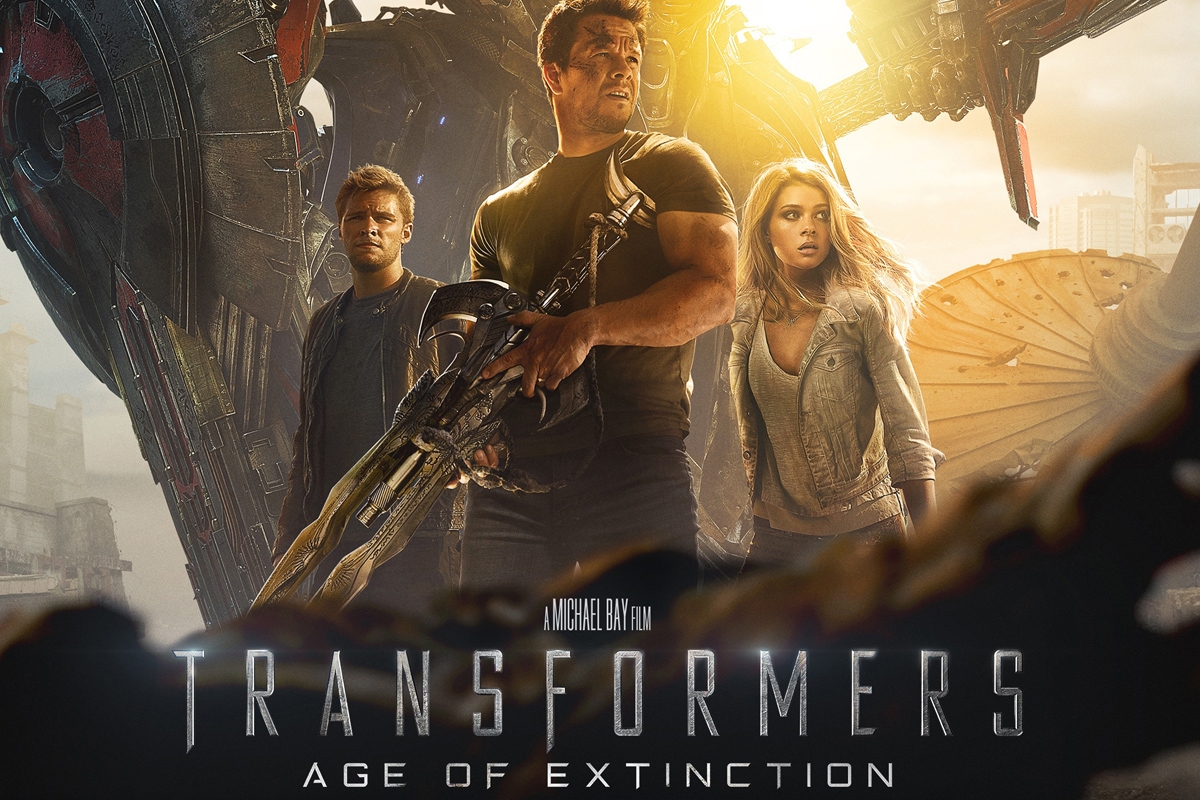

A good example of enhanced stereo is the Beatles’ “Come Together (2019 Mix)” from Abbey Road (Dolby Atmos, Apple Records/Apple Music). John Lennon’s vocals were portrayed above my center-channel speaker, with Ringo Starr’s drums slightly to the right. George Harrison’s guitar was to the left and Paul McCartney’s backup vocals were evident in all of the channels. The reverb of the handclaps started in the front and echoed to the rear speakers for a nice effect. In this type of mix, the song sounds fresh, but the effects don’t detract from the performance in front of you.

Another example is the expanded edition of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers’ album Moanin’ (Dolby Atmos, Blue Note Records/Tidal). On the album’s title track, the band was nicely rendered in the front of the soundstage, with Bobby Timmons’s piano and Lee Morgan’s trumpet to the left, and Blakey’s drums prominently to the right. The surround and ceiling speakers just provided a sense of the space of the venue, and did not detract from the sound images of the band members. By comparison, in the two-channel version of “Moanin’ (Remastered)” (MQA, Blue Note Records/Tidal), there was no sense of soundstage, with all the musicians seemingly squeezed into a space between my front speakers.

One final example of spatial audio providing a realistic illusion of a performance is an album that I also own on SACD—Sam Cooke at the Copa (Dolby Atmos, BKCO Records/Apple Music). This is a classic you-are-in-the-audience mix, with applause in the rear speakers. When listening to “If I Had a Hammer (The Hammer Song),” Cooke and his band were mostly coming from the center speaker, without much left-to-right spread. When he sings “I’ve got a bell,” the sound of the bell came from the center speaker as well. I listened to this track back-to-back with the SACD (ABKCO Records 99702), and the SACD mix was better. Although the Apple Music spatial audio mix was much cleaner sounding, the band was more spread out between the front three speakers on the SACD. The bell sound came from the right of the center speaker, rather than directly from the center speaker. When Cooke gets the audience singing, the audience could be heard not just in the front soundstage, but in the middle of the room, too.

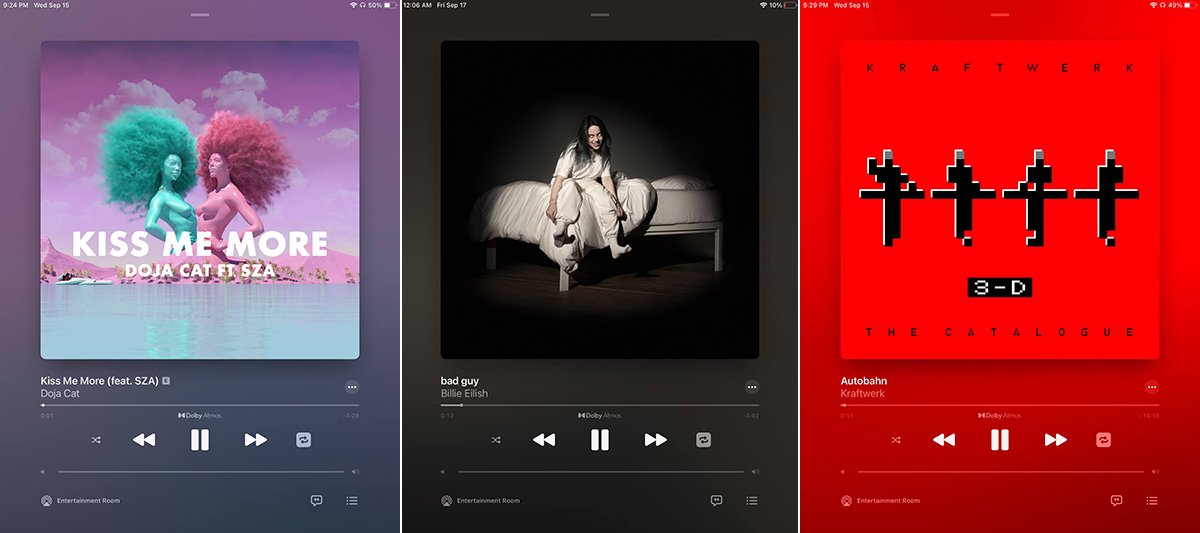

From the other perspective on spatial audio, where it can be seen as a new medium, the artists’ imaginations can go wild. From a purist two-channel view, this could be the worst thing in the world. If you have an open mind, you may feel differently. One of the best spatial audio tracks I heard on Apple Music was Doja Cat’s “Kiss Me More (feat. SZA),” from the album Planet Her (Dolby Atmos, Kemosabe Records/Apple Music). Although the music just seemed vaguely there in the front of the room with the main vocals coming from the center speaker, the backup vocals were prominently placed in the surrounds. The backup vocals interacted with the front speakers producing the main vocals, and, in my view, the song was greatly enhanced by this effect.

Another good mix is Billie Eilish’s “Bad Guy” from the album When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? (Dolby Atmos, Interscope Records/Apple Music). With this track, Eilish’s backup vocals were elevated from the floor speaker locations and surrounded my listening position. When Eilish starts to sing the lyrics, the vocals came from the center speaker. The music is mixed in the other speakers, including the surround channels, and when she utters “Duh,” her voice popped back to the center speaker. The LFE channel is also used very effectively on this track, my subwoofer rattling the walls with the synth bass.

Another interesting mix is from Kraftwerk’s 3-D: The Catalogue album (Dolby Atmos, Parlophone Records/Apple Music). If you think your ceiling speakers don’t really contribute much to Dolby Atmos Music tracks, listen to “Autobahn.” The song begins with a car starting up and driving from back to front. All kinds of sounds are pushed up to the ceiling, and this track is a cacophony of sound through all your speakers. Some of the sound is low resolution, about MP3 quality. This is manifested through a thin-sounding midrange and a lack of high-frequency extension. This was something I noticed at times with other tracks as well—if you’re a purist audiophile, and you’re used to sonic traits such as copious amounts of high-frequency air, you might be put off by the sound of some of the music in spatial audio recordings. When you look at Apple Music’s spatial audio literature, you can see they are trying to cover a number of different kinds of devices—headphones, iPads, computers, and home audio systems. It’s no surprise that some of the mixes are subpar from a resolution perspective.

Conclusion

My journey through Apple Music’s spatial audio and Tidal’s Dolby Atmos Music was a fascinating one. As a fan of multichannel audio on SACD and DVD-Audio, I lamented when they became obsolete or relegated to niche formats. It’s great to see new artists and producers taking up this medium not only to enhance stereo reproduction, but also to come up with new and creative uses for the extra speakers available in the formats. I like the clout of Apple Music behind it as well—it has a real chance of staying relevant. On the negative side, one thing that put me off was the difficulty in locating spatial audio and Dolby Atmos tracks in both Apple Music’s and Tidal’s catalogs.

I wasn’t too concerned by the low-resolution sound I heard at times—the enhanced imaging and the “bubble of sound” that the format creates have their own intriguing qualities. I briefly borrowed my son’s Apple AirPods (said to be Dolby Atmos compatible) and listened to some music on my iPad with spatial audio enabled, and I was very disappointed. I imagine this is the way most people are going to experience spatial audio, and it doesn’t come close to the immersive sound you’ll hear with multiple speakers in an ambient space. There was almost no sense of the three-dimensional sound that I heard with my system.

The final thing I want to point out is that the genres which I most enjoy listening to—jazz vocals and trios—were largely absent from these formats in both catalogs. Nevertheless, if you’ve got a Dolby Atmos system in your home and you’re not a Tidal or Apple Music subscriber, I’d recommend giving either service a try and hear spatial audio for yourself. You might be surprised.

. . . Vince Hanada