Music lovers have been trying to solve a problem ever since they began collecting recordings: How to have convenient access to large music libraries?

The jukebox, popular beginning in the 1940s, was an early attempt to approach the issue, giving listeners rapid access to dozens of 78rpm, then 45rpm singles, and finally entire LPs. It was, however, largely a commercial solution. For home audio, record changers permitted the queueing up of albums to provide hours of uninterrupted music, and gained popularity with the Elac Miracord, back in 1960. In the mid-1970s, my dad had a BSR record changer connected to his quadraphonic system. When the first LP was finished playing, the next one, suspended above it, would drop into place, the tonearm would rise, position itself over the lead-in groove, lower, and begin playing. This must horrify owners of today’s 180 and 200gm pressings, but it obviated the need to change the record every 20 minutes or so. Record labels supported the practice by numbering the sides of their boxed sets in record-changer sequence: in a three-record set, disc 1 comprised sides 1 and 6, disc 2 sides 2 and 5, and disc 3 sides 3 and 4. Let the stack play through sides 1-3, turn the stack over, and play sides 4-6. Some changers even flipped records over. Later, of course, came CD changers.

It was with the personal-computer revolution that the possibility of having all your music easily available became feasible. Microsoft, Apple, and many independent software vendors envisioned the home computer as a home’s entertainment center, with such solutions as Windows Media Player and iTunes. You could shuffle through all of your music -- and, with the rise of file-sharing websites such as Napster, all of everyone’s music -- in virtually endless playlists. What has changed since the mid-2000s is a shift to, in the words of Satya Narayana Nadella, CEO of Microsoft, “mobile-first, cloud-first.” In short, we now play music from our smartphones and file servers. Various degrees of management are available, from curating playlists on your own DLNA server on a LAN, to allowing a streaming service anywhere in the world to act as your DJ.

Chromecast devices

With sales of some 55 million across all supporting devices, Google’s Chromecast is among the most popular options in its category. On July 24, 2018, Google’s blog The Keyword celebrated the fifth anniversary of Chromecast’s release with engineer Majd Bakar, who explained the motivation for the product. While streaming services, video and/or audio -- e.g., Netflix, YouTube, Pandora, etc. -- had made substantial headway in the delivery of entertainment, they were often consumed on a computer because the television interfaces were hard to use, especially with typical remote controls, or required management by a computer. Bakar’s approach was to separate the consumption (the TV) from the transport and the search/queuing interface (moved to a smartphone), with the bridging device between them being as small and unobtrusive as possible.

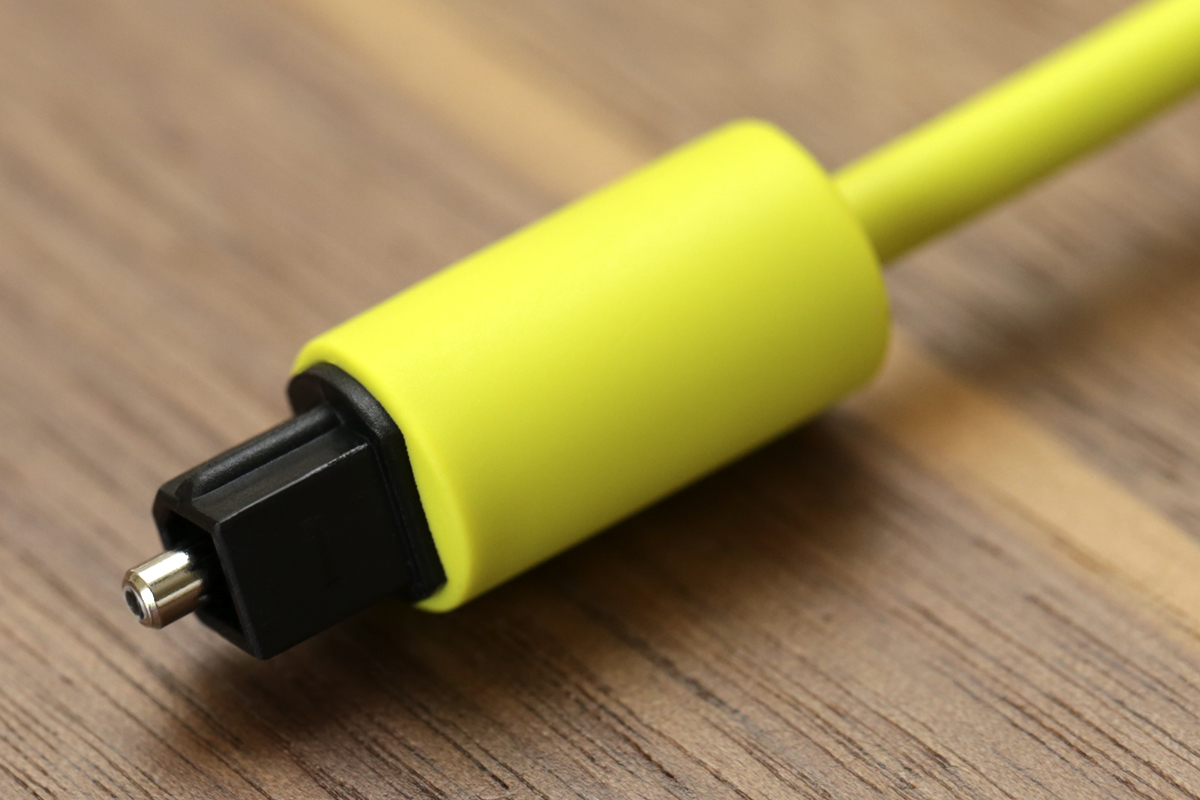

The first Chromecast device, released in 2013, was a USB-powered HDMI dongle offered for $35. It didn’t include an infrared remote control, but it could be managed from a smartphone via Wi-Fi (and, to a lesser degree, over the HDMI CEC protocol). Subsequent releases from Google were Chromecast Audio, in 2015, also for $35 (more about this below) -- and, in 2016, Chromecast Ultra, which supports 4K and HDR ($69). All current-generation Chromecast devices are enclosed in discs that look like miniature LPs and, rather than with a dongle, are connected to a TV or electronic component by a short wire, for greater flexibility in placement. While all Chromecasts are Wi-Fi devices, they also support a wired Ethernet connection over an optional USB power adapter.

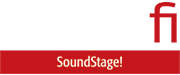

The Chromecast, Chromecast Ultra, and Chromecast Audio devices can all be used for music-only listening, but pack different connectivity options. The Chromecast and Ultra models are designed to output via HDMI to an AVR or TV (PCM output via HDMI can be tapped by several DACs and HDMI switches as well), while the Chromecast Audio disc has a 3.5mm socket that can be used with an analog or mini-TosLink (digital optical) interconnect. With the release of Chromecast Audio, Google also went after the multiroom audio market by permitting the synchronized, simultaneous playback of multiple devices, much as with Sonos systems. With this approach, Chromecast Audio can be incorporated into existing stereos and speakers for a tenth the cost of a Sonos Connect.

While the Chromecast Audio’s built-in DAC, based on the AKM AK4430 chipset, supports high-resolution audio, its analog sound quality -- very much like that of a typical smartphone -- leaves much to be desired. Serious hi-fi enthusiasts won’t be impressed. Instead, Chromecast Audio’s most compelling feature for audiophiles is its digital optical output, by which one can link to another DAC. At release, Chromecast Audio was limited to 24-bit/48kHz resolution; via an automatic firmware update later in 2015, 24/96 became available.

The Chromecast Audio codec supports AAC, LPCM, MP3, Vorbis, and, critically for audiophiles, FLAC. In the last five years, Chromecast has been implemented in many products from many manufacturers: dozens of brands of TVs; speakers from the likes of Bang & Olufsen, Grundig, Harman/Kardon, JBL, and Polk; AVRs from Onkyo/Integra and Pioneer; NAD’s C 338 integrated amp ($649), which I reviewed in 2017; and multiroom solutions from Teufel and VSSL. The Google Home product line of three models of Assistant-powered smart speakers, with Chromecast built in, is clearly a future direction for the technology. App support of the Chromecast protocol has grown from the four companies at launch -- YouTube, Netflix, Google Play Music, and Google Play Movies & TV -- to over 20,000 in 2015. It’s now rare to find a recent streaming-service app on an Android device that doesn’t support Casting.

Chromecast protocol -- Google Cast

Chromecast’s approach to delivering content from a smartphone to a screen and speakers differs from those of most of its competitors. For example, Bluetooth is effectively a speaker output of the phone, beaming compressed digital content directly from the phone to the target device. In many applications, however, Chromecast uses the phone only to control and manage signals -- audio/video content flows from the server/cloud service to the Chromecast device, the phone intervening only to, say, skip a track. Streams to Chromecast receivers originate from mobile and web apps (sender apps), or as a screen-mirroring technology from the Google Chrome web browser, using the Cast extension running on a computer. The result is that once playback has begun, the phone itself can be turned off (thus saving the battery) or be used for other purposes, such as talking, texting, or web browsing, without causing latency in the audio stream.

The ultimate solution?

Chromecast isn’t perfect. The choice not to include an infrared remote, relying instead on a phone app, is actually not a simplification -- control of playback requires more taps on a phone, especially if you lock the phone for security, than would a remote. However, there are ways to get around this. Since HDMI CEC is supported, many TVs and AVRs can control Chromecast with their own remotes, and the NAD C 338 (supporting 24/192 streams) implemented Chromecast with playback (pause, skip, etc.) via its bundled infrared remote. Logitech Harmony’s Hub product can manage playback on Google’s Chromecast devices via Wi-Fi, as these Chromecasts have no infrared receiver.

Then there’s Google’s loose control over the app ecosystem, which has led to inconsistency in implementation of the Cast interface, and thus to confusion for some users over how to Cast. For example, my preferred local network playback app for Android devices, Hi-Fi Cast + DLNA, buries the Chromecast selection in its DLNA renderer menu, which is difficult to find. Google Play Music, on the other hand, has a very obvious one-tap icon, which makes it much easier to locate. Finally, reliably maintaining the control connection from some apps is an issue, which creates reliability problems.

Nonetheless, Chromecast Audio is among the best options for the dream of easy access to large music collections. With streaming services and Google’s Chromecast, access to music from anywhere, anytime, by anyone has become possible, practical -- and very inexpensive.

. . . Sathyan Sundaram