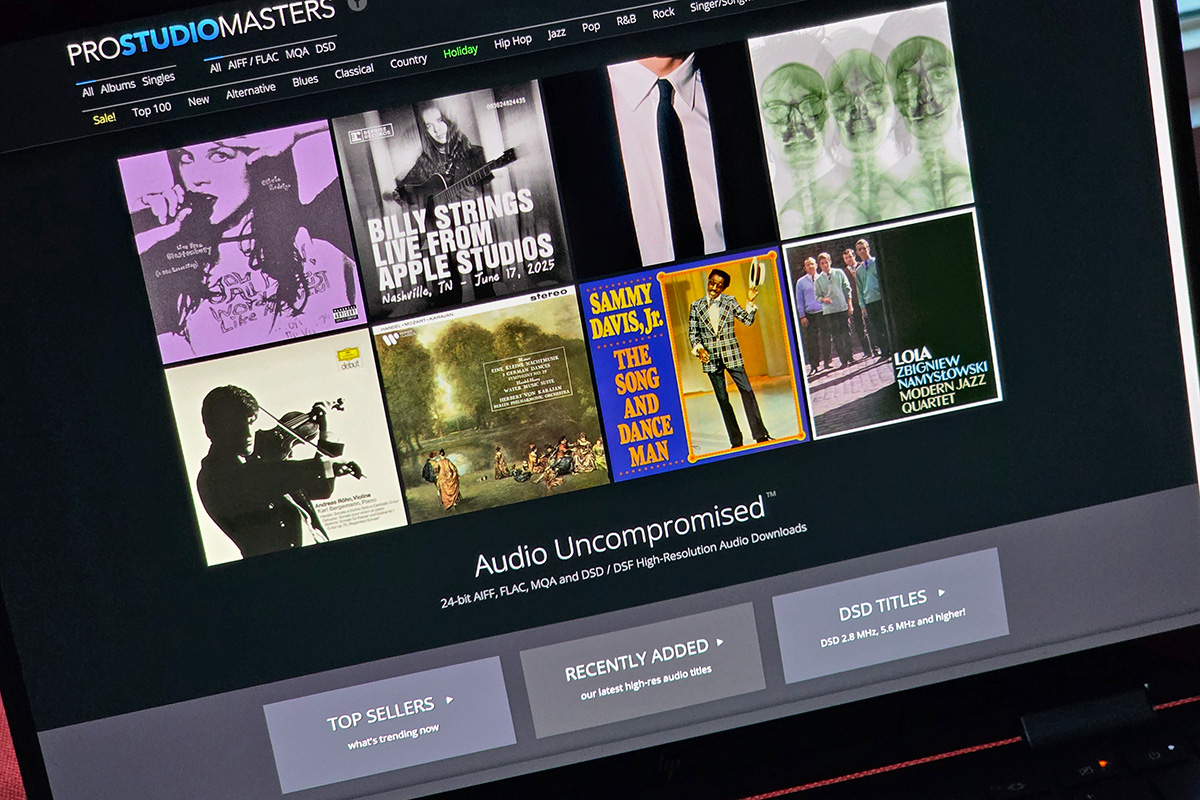

Seven years ago, when Gordon Brockhouse asked “Are downloads dead?” on this site, the question felt relevant but premature. Downloads were in obvious decline, streaming was ascendant, and the writing seemed to be on the wall. Today, with streaming accounting for 69% of global music revenues and downloads representing just 2.8% of the market, you’d think the answer would be obvious. Yet download stores are still operating here in 2025, serving a dedicated, passionate audience that has no intention of giving up ownership.

The numbers tell one story, but the reality is more nuanced. According to the Global Music Report 2025 from the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), global sales of downloaded music shrank dramatically from a 2014 peak of US$4.4 billion to roughly US$829 million in 2024. But the people who continue to buy downloads aren’t simply clinging to the past. They’re making deliberate choices about how they consume music, driven by concerns about ownership, quality, permanence, and artist support that streaming simply cannot address.

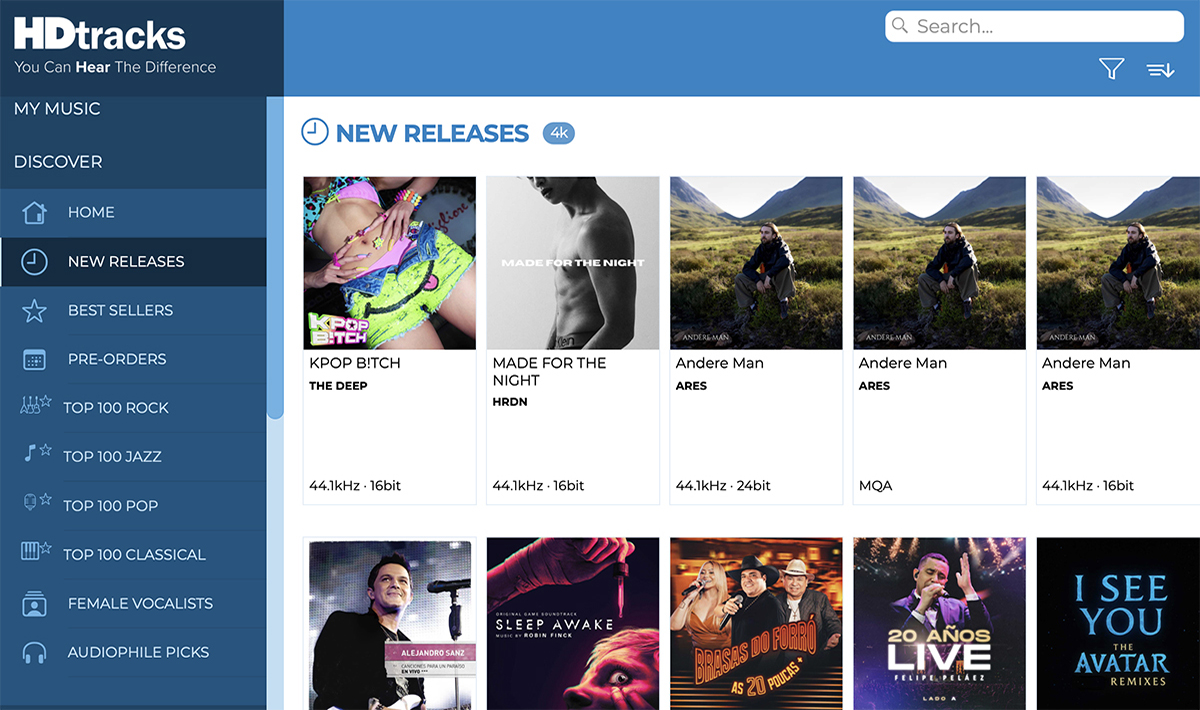

I caught up with David Chesky, CEO and cofounder of HDtracks, one of the first online stores to offer high-resolution downloads, and Dan Mackta, managing director of the France-based streaming service Qobuz, to get their perspectives on where things currently stand with downloads.

The state of the download market

IFPI’s most recent Global Music Report paints a stark picture. Total worldwide streaming revenues exceeded US$20 billion for the first time in 2024, with 752 million paid subscription accounts worldwide. Compare that to the aforementioned US$829 million for digital downloads and other non-streaming digital formats, a continued drop from previous years, although the rate of decline has slowed.

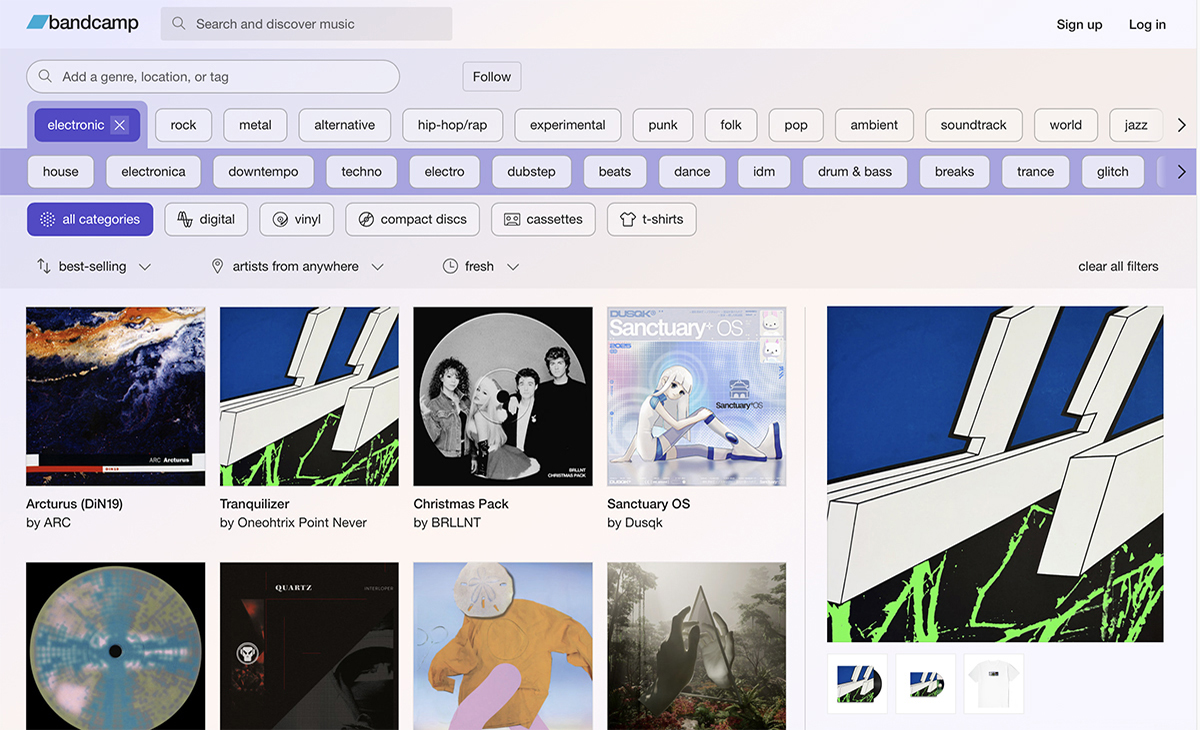

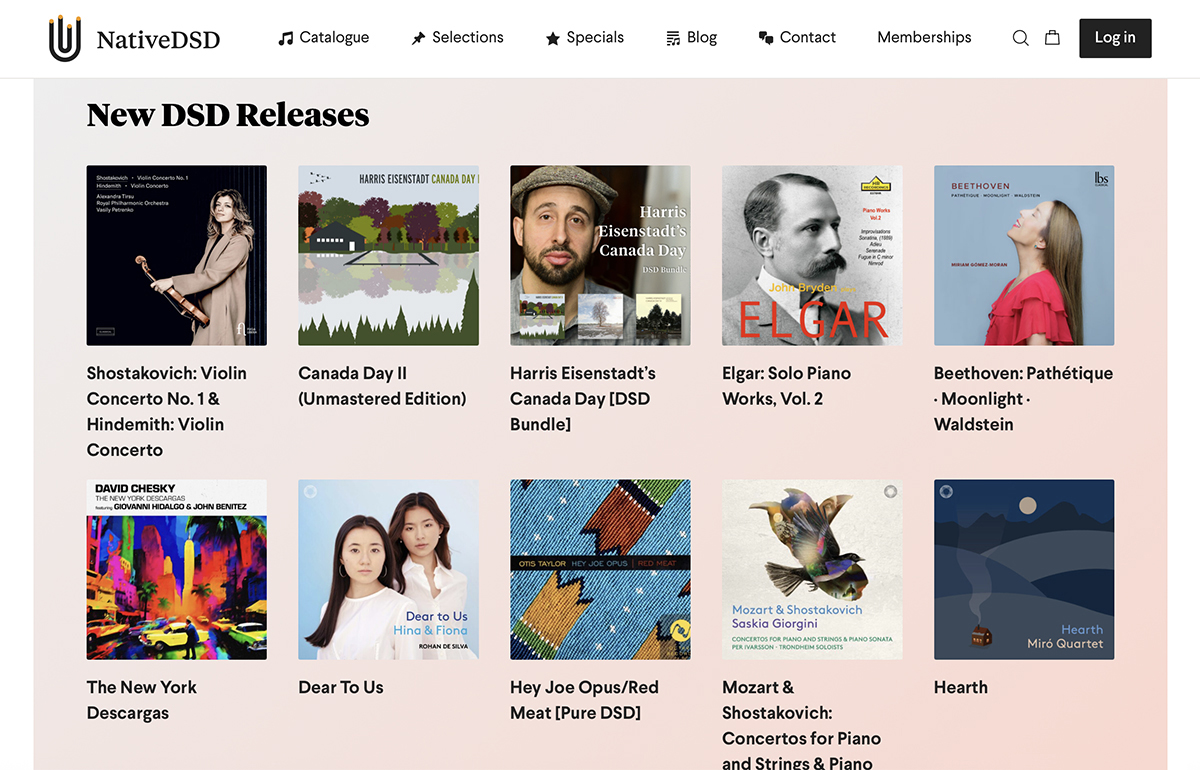

Yet the download ecosystem persists. HDtracks, which pioneered high-resolution downloads in 2007, is still going strong. Qobuz continues to operate both streaming and download services. Bandcamp reported that fans spent over US$3.1 million in a single day during their December 2024 Bandcamp Friday event. ProStudioMasters, 7digital, and numerous specialized sites like NativeDSD and eClassical continue to serve niche audiences. These platforms aren’t just surviving. Some are thriving by serving specific communities that mainstream streaming largely ignores.

Dan Mackta

Dan Mackta

Qobuz’s Mackta reports that “download sales in Europe are still strong and have been growing slightly, in contrast to the overall market, where the format has seen steep decline.” More surprisingly, he notes that downloads are “growing faster in the US and Canada than Europe at this point,” suggesting this form of collecting may be finding renewed relevance with North American music fans.

The collectors: the urge to curate

For many music lovers, the desire to collect is fundamental. It’s not about hoarding. It’s about curation, about building a personal library that reflects the musical journey of each owner. The ownership impulse hasn’t disappeared in the streaming age; it has evolved.

Chesky puts it simply: “Collecting is a natural thing. People like to collect LPs, CDs, and downloads; this way they own their music and no one can take it away from them.” That sentiment reflects a core motivation among download buyers: the desire for permanent, irrevocable ownership.

David Chesky

David Chesky

The overwhelming abundance of streaming (Apple Music’s 100 million tracks, Spotify’s similarly sized catalog) has paradoxically made curation more valuable, not less. When everything is available, nothing feels particularly special. Downloads offer a way to build a collection that means something.

This collecting impulse manifests differently across age groups. Back in 2018, Mackta observed that “boomers like to collect, millennials prefer to stream.” But that’s proven to be an oversimplification. Mackta now reports that “the profile of download consumers on Qobuz has expanded to include DJs, who are looking for lossless files across a wide variety of genres, and conscious music fans who like to buy an album as a download in order to better compensate the artists.”

The practical benefits of collection-building are also real. Smart playlists in applications like Audirvana or Roon can do things streaming services simply can’t: automatically queue up your top-rated tracks from the 1990s that you haven’t heard in six months, create dynamic mixes based on detailed metadata, or shuffle through the “dinner-party jazz” collection you spent years assembling. These capabilities matter to people who think deeply about their music libraries.

An interesting phenomenon has emerged around K-pop, a genre where Qobuz is seeing “a strong business” in downloads. This is driven by a fan culture where physical and digital ownership of favorite artists’ work is an inherent part of community participation and collecting. Fans want permanent copies of releases as collectible items, not just streaming access.

The quality seekers: beyond CD resolution

One of the most vibrant corners of the download market serves audiophiles seeking quality beyond what streaming offers, or at least, beyond what most streaming offers reliably. While Tidal, Qobuz, Apple Music, and even Spotify now provide high-resolution streaming, download stores still offer advantages for the discerning listener.

Sites like HDtracks, NativeDSD, ProStudioMasters, and Qobuz’s download store, as well as specialized services like High Definition Tape Transfers, provide music in formats ranging from 24‑bit/192kHz FLAC to DSD256 and even DSD512. These files can preserve detail and dynamic range that even high-resolution streams may not, depending on how the streaming service implements its hi‑rez tier.

The technical reality, however, is more complex than some might assume. When asked whether downloads sound better than Qobuz’s Studio streaming tier for users with high-end equipment and good internet, Mackta’s response was direct: “It’s the same file. Does it matter if it’s streaming from the cloud or local storage? You tell me.”

Yet the perception persists among many listeners that downloads sound better. Chesky maintains that downloaded files have “no jitter over 4000 miles of cables, and a more palpable, dense sound compared to streaming.” Whether these differences are measurable or perceptible, they matter to buyers who are willing to pay premium prices for what they believe is superior sound quality.

When it comes to formats, Chesky reports that “people like 192/24 and any type of DSD,” though he notes a concerning trend: “Downloads are shrinking as people are choosing convenience over true HD sounds. Streamers are doing better, musicians make less, sound quality goes down: the race to the bottom.”

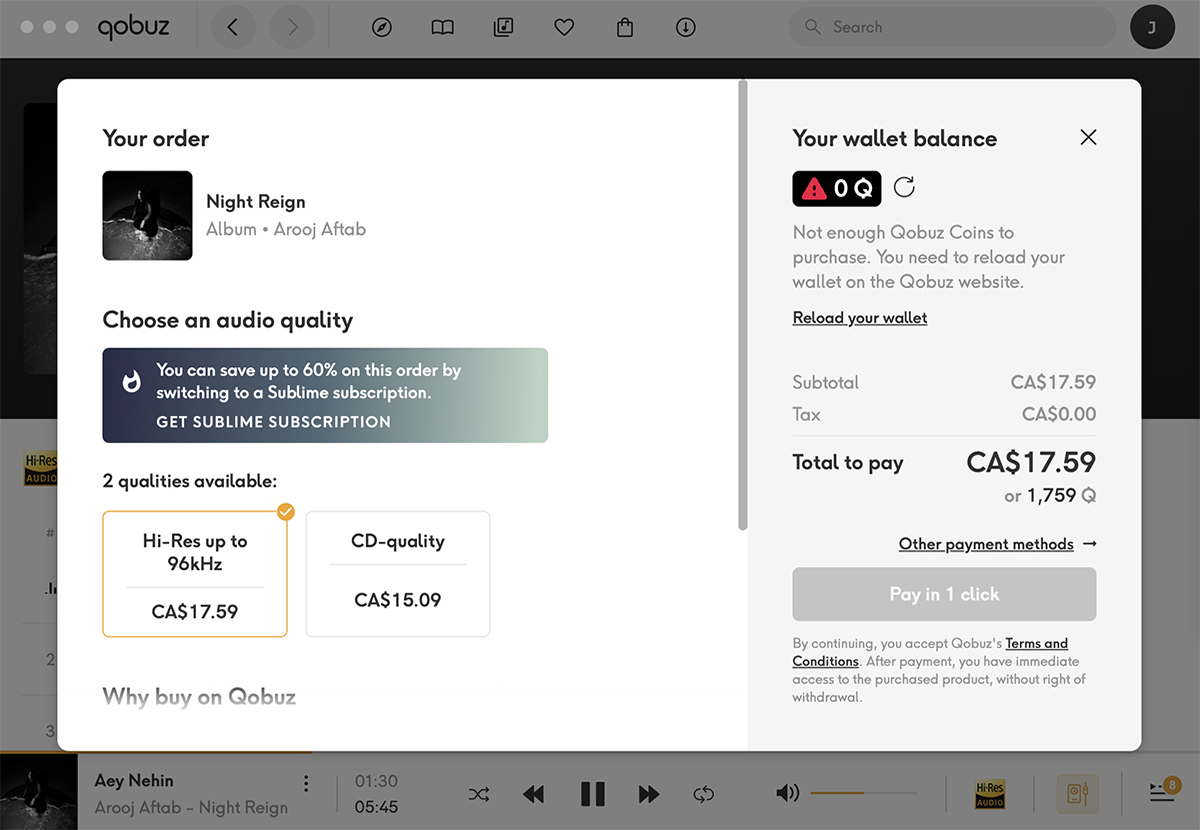

Mackta confirms that “generally people are buying the highest-resolution version available” and that Qobuz has “recently started selling DSD/DXD downloads, but it is still a small fraction of our overall sales.” For the truly committed audiophile, these ultra-high-resolution formats represent the pinnacle of digital audio.

The audiophile community remains passionate about these formats. Forums light up with discussions about whether DSD256 sounds better than 24/352.8 DXD, whether certain DACs handle one format better than another, and which labels do the best job with their hi‑rez transfers. Services like High Definition Tape Transfers, which specializes in direct transfers from vintage reel-to-reel tapes to DSD, have developed cult followings among jazz and classical enthusiasts.

The security-conscious: when ownership matters

Perhaps the most compelling argument for downloads has become apparent just recently: the realization that streaming access is fragile and contingent. Music can disappear from streaming services without warning—and it does, regularly.

Chesky is emphatic on this point: “First of all, streaming platforms can—and often do—remove albums. Some of my favorite personal albums have disappeared overnight.” This isn’t a theoretical concern. It’s a regular occurrence that has shaken many music lovers’ faith in the permanence of streaming libraries.

Albums vanish when licensing deals expire. Artists pull their catalogs for business reasons. Services shut down (remember Google Play Music? Rdio? Groove Music?). Even songs you’ve “saved” to your library can become unplayable overnight. Taylor Swift’s 2014 removal of her entire catalog from Spotify, though eventually reversed, demonstrated how quickly access can evaporate.

Interestingly, Mackta reports that at Qobuz, they “haven’t seen this phenomenon” of albums disappearing driving significant download sales, suggesting that while the concern is real, it may not be the primary motivation for most download purchases. Perhaps Qobuz’s catalog has been more stable, or perhaps users haven’t yet fully internalized the impermanence of streaming access.

The phrase “if buying isn’t owning, then piracy isn’t stealing” has become a rallying cry in videogame and film communities facing similar issues. Music fans increasingly share this concern. When you pay for a download, you own the file. You can back it up, copy it to multiple devices, keep it on external drives, and access it regardless of whether or not the service that sold it to you is still in business. You’re not dependent on maintaining a subscription, on the service keeping its licensing deals current, or on the internet being available.

This ownership model is particularly appealing to those who witnessed the mass transition away from physical media. They saw Tower Records close up shop, watched online stores come and go, and experienced firsthand what happens when access to music depends on someone else’s infrastructure. A hard drive full of FLAC files feels more permanent than a streaming library that could theoretically disappear if a service shuts down or if you no longer want to shell out for the subscription.

The argument that downloads are “just licenses too” is technically true but practically irrelevant. DRM-free downloads (which most quality stores provide) are effectively your files. No one is going to revoke your FLAC copy of Random Access Memories just because a licensing deal expires.

The artist supporters: direct relationships

For many music fans, particularly those who follow independent and niche artists, downloads represent a better, more direct way to support musicians than streaming can ever offer.

The economics are stark. Chesky provides specific numbers: “An artist with a direct deal through HDtracks can make over $17 per download. To earn that same amount on Spotify, you’d need roughly 1700 streams of a full album.”

He illustrates the challenge for niche genres: “Jazz, blues, and classical music don’t have massive audiences. The customer base is limited. For example, if a jazz artist sells 1000 albums directly at $29 each, that’s about $20,000 in revenue. To earn that same $20,000 on a streaming platform, they’d need around 7 million streams of the album. You can sell 1000 albums, but no jazz artist is going to get 7 million full-album streams.”

Mackta explains Qobuz’s model: “We have published the fact that we pay, on average, over $18 per thousand streams. On a $25 album sale, our margin is about 30%, and then the artist is paid based on their deal with their label.” While both streaming and downloads ultimately depend on label contracts, the direct nature of a purchase transaction feels more tangible to many fans.

Bandcamp has built its entire business on this premise. The platform gives artists an average of 82% of every sale, with Bandcamp taking just 10% on merchandise and 15% on digital music (compared to the fractions of a penny per stream from Spotify or Apple Music). This model has resulted in US$1.6 billion paid to artists since Bandcamp’s founding.

The appeal isn’t just economic. It’s emotional and philosophical. Chesky frames it passionately: “When you buy an album, you’re not just getting the music. You’re supporting the artist. There’s no real path forward for young artists today if their work only lives on streaming. For most, it’s a career that leads nowhere financially. If you truly love music, support the artists who create it. Buy their albums, go to their shows, and help keep music alive as an art form, not just background noise.”

This matters especially for genres and music scenes that operate outside the mainstream. Electronic music producers, ambient artists, experimental composers, jazz musicians, and classical performers often find that Bandcamp or direct sales generate significantly more income than streaming, even if stream counts look impressive.

Independent labels and artists also report that download customers tend to be more engaged fans. They’re more likely to buy merchandise, attend concerts, and spread the word about music they love. The act of purchasing creates a stronger connection than simply hitting play on a streaming service.

The treasure seekers: finding what streaming doesn’t have

Despite the massive catalogs of streaming services, content gaps remain. Some artists and labels refuse to participate in streaming. Others have back catalogs that haven’t been digitized or licensed for streaming. Still others offer exclusive releases only through their own channels.

Mackta estimates that, of Qobuz’s catalog, “probably something like 95% is available for both streaming and download.” That remaining 5% represents an important niche: “In some cases, a rights-holder will have licensed a track for streaming only, and in some cases labels do not like the streaming business model and only make their catalogs available as downloads.”

Classical music presents particular challenges. While the major symphonies and operas are well-represented on streaming, extensive back catalogs from specialized labels like Hyperion Records, BIS, Chandos, and CPO are often incomplete or absent. If you’re looking for a specific recording of a Shostakovich symphony by a particular conductor, streaming might not have it, but you can often find it as a download.

Mackta confirms that downloads remain “mostly classical and jazz” in terms of genre strength, reflecting both the availability gaps in streaming and the particular concerns these audiences have about quality and permanence.

The same applies to vintage jazz recordings, small-label releases, and recordings by living artists who maintain tight control over their work. Electronic music, particularly in subgenres like ambient, techno, and experimental music, frequently appears first or exclusively on Bandcamp and similar platforms.

For DJs and music producers, downloads are still essential. Many DJs prefer to own their music rather than depend on streaming, both for reliability and for the ability to create specialized mixes and edits. Electronic-music producers often purchase individual tracks or sample packs that simply aren’t available through streaming services.

The format enthusiasts: choice and flexibility

Downloads offer format flexibility that streaming can’t match. Want FLAC for home listening, ALAC for your Apple devices, and MP3 for the car? With downloads, you can have all three. Need WAV files for DJ software? Done. Want to convert to a specific format for your particular audio player? Go ahead.

This flexibility matters to people with specialized equipment. Owners of high-end DACs, digital audio players (DAPs) like those from Astell & Kern or FiiO, and music servers like those from Roon and Lumin often prefer to manage local libraries rather than rely on streaming.

Dedicated digital audio players can handle everything from MP3s to DSD512 files. These devices offer better digital-to-analog conversion than typical smartphones, more storage than streaming apps, and complete independence from internet connectivity. They’re popular among commuters, travelers, and anyone who values sound quality but doesn’t want to rely on a network connection for streaming.

The hybrid approach: streaming for discovery, downloads for keeps

One apparent trend is the hybrid approach many listeners have adopted: streaming for discovery and casual listening, downloads for music they truly love. This is not new; it was referenced in the 2018 article and has become increasingly common since. Fewer purchases get made, but those purchases are meaningful. They’re the recordings that people want to own permanently, albums that may not be available on streaming, or releases purchased specifically to support the artist directly.

Platforms like Qobuz have embraced this model by offering both streaming subscriptions and a download store, often with discounts for subscribers. Their Sublime tier includes both hi‑rez streaming and discounts on downloads, acknowledging that many users want both options.

However, Mackta admits the crossover isn’t as strong as one might hope: “I wish it would lead to even more download purchases, but to be honest, the number of cross buyers who subscribe to streaming and also buy from our download store is not that big.” This suggests that even when the hybrid model is available, most users settle into one consumption pattern or the other.

Looking forward, Mackta envisions continued evolution: “Hybrid. It would also be great to be able to subscribe to individual artists. Let’s see where things go.” This artist-subscription model could represent a middle ground between the all-you-can-eat buffet of streaming and the deliberate curation of downloads.

The price consideration

Economics obviously plays a role in this discussion. A streaming subscription costs roughly US$10–25 per month depending on the service and tier. For that, you get access to tens of millions of tracks. No listener could hope to match that value by purchasing downloads.

But the value equation isn’t always straightforward. If you listen to relatively little new music (for example, if you’re someone who plays your favorite albums repeatedly rather than constantly seeking novelty), downloads might actually be more economical over time. A $50 annual music budget buys several albums you’ll own forever, versus a $120 annual streaming subscription that evaporates the moment you stop paying.

For older listeners who’ve already built extensive collections (whether vinyl, CD, rips, or downloads), the calculus is different. They’re not trying to access everything; they want to own the specific things they love. Streaming offers poor value for this use case.

Additionally, the psychological aspect of ownership shouldn’t be dismissed. Purchases feel more meaningful than subscriptions. The albums you buy become part of your permanent library, your musical identity. They don’t require ongoing financial commitment to access. There’s freedom in that permanence.

Chesky acknowledges the market reality: “Downloads are like albums. Pop always wins big, while jazz, classical, and blues remain niche markets.” Yet these niche markets are large enough to sustain his business and others like it.

Challenges and the future

Running a download store in 2025 isn’t without challenges. When asked about the biggest operational challenge for HDtracks, Chesky is blunt: “Getting people to see the value of owning music and supporting musicians.”

The question of streaming continues to loom. In 2018, Chesky told Gordon Brockhouse that HDtracks had streaming capabilities ready but wasn’t prepared to launch. Seven years later, his position hasn’t changed: “Yes we do, but what is the point if we will put all our musicians out of business?”

This perspective (that streaming fundamentally undermines musicians’ ability to earn a living) runs throughout the download community. It’s a view that resonates with fans who remember when artists could build sustainable careers from album sales alone.

Yet the undeniable reality is that downloads clearly aren’t going to reclaim their mid-2000s dominance. The convenience, affordability, and discovery features of streaming are too compelling for mass-market adoption of downloads. The trajectory is clear: streaming will continue to grow, and downloads will continue to shrink as a percentage of the market.

But shrinking doesn’t mean disappearing. The download market has stabilized at a level that, while tiny compared to streaming, is large enough to sustain a healthy ecosystem of stores and services. These businesses serve specific communities: audiophiles seeking maximum quality, collectors who value ownership, fans wanting to support artists directly, and listeners concerned about the impermanence of streaming.

There’s an obvious comparison to vinyl here. Vinyl represents less than 5% of music revenues, yet it’s experiencing its 18th consecutive year of growth, with 2024 seeing another 4.6% increase. Vinyl persists because it serves needs that digital formats can’t: the tactile experience, artwork, ritual, and a particular sonic character that some listeners revere.

Downloads occupy a similar space. They serve real needs for real people, even if those people represent a small minority of listeners. The key difference is that downloads are more practical than vinyl. There are few storage logistics, no fragility, and perfect quality preservation, all while still offering the ownership and permanence that streaming glosses over.

The stores serving the download market have adapted. They’re no longer trying to compete with streaming on convenience or catalog size. Instead, they’re emphasizing quality (hi‑rez formats), curation (specialized genres and labels), artist support (higher payouts than streaming), and permanence (DRM-free files you truly own). This positioning has allowed them to survive and, in some cases, thrive.

A niche that persists

Seven years ago, Gordon Brockhouse concluded that downloads weren’t dead, they had simply found their niche. That conclusion has proven accurate with the passage of time, perhaps more so than he anticipated. The download market has contracted dramatically, but it has not collapsed. It has transformed into a specialized market serving specific needs that streaming cannot or will not address.

For audiophiles, downloads offer quality and format flexibility; even if the perceptible differences from high-resolution streaming are debatable, the perception of quality matters. For collectors, they provide ownership and curation. For subscription-resistant listeners, they deliver permanence and independence from corporate platforms. For artist supporters, they enable direct financial relationships that streaming simply cannot match. For availability seekers, they provide access to music that streaming services don’t carry.

These aren’t trivial concerns or nostalgic attachments. They are legitimate reasons to prefer ownership over gated access, to value quality over convenience, and to choose direct support over algorithmic distribution.

Chesky’s closing words capture the philosophy of the download faithful: “People young or old tend to buy the bands and music they love.” In an age of unlimited streaming access, that simple act of purchase—of choosing to own rather than merely access—has become a statement of values.

The music industry has room for both models. Streaming serves the vast majority of listeners, providing incredible value and convenience. Downloads serve a smaller but passionate minority who have specific needs that streaming doesn’t meet. That minority is large enough to support an ecosystem of stores, sufficient to justify continued investment in high-resolution formats, and engaged enough to keep downloading music despite easy access to comprehensive streaming libraries.

Downloads aren’t dead, they’re just not for everyone anymore. But for those who value what downloads offer, they’re more relevant than ever. In an increasingly ephemeral digital world, where access can vanish at any moment, there’s something deeply appealing about files you own, stored on drives you control, playable regardless of subscription status or internet connectivity.

Paying for and downloading content is a conscious choice to own rather than rent, to curate not consume, to support instead of stream. For a subset of music lovers, that choice matters—and as long as it does, downloads will endure.

. . . AJ Wykes