Typically, articles predicting developments for the coming year come out in early January, or even late December. But here we are, two weeks into February, and Simplifi finally has a feature outlining what we can expect from music streaming in 2023. Do I feel badly about this delay? Not in the least. Because when it comes to lateness, I have nothing on Spotify and Apple Music. Those streaming giants have both missed self-imposed deadlines by well over a year. With that excuse out of the way, here are three streaming stories I’ll be watching in 2023.

Whither Spotify HiFi?

Almost exactly two years ago, at its inaugural Stream On event on February 22, 2021, Spotify announced plans to offer lossless music. Since its inception, Spotify has used lossy compression to distribute music. “For those listeners really passionate about audio quality, later this year, we’ll be launching a new subscription offering—Spotify HiFi,” said Jeremy Erlich, Spotify’s global co-head of music, during the event.

As we all know, Spotify HiFi didn’t launch in 2021. Or 2022.

Some observers have speculated that Spotify was blindsided by Apple’s announcement in May 2021 that it would make its entire Apple Music catalog available in lossless, with a substantial number of tracks available in resolutions up to 24-bit/192kHz. The service went live on June 7, the first day of Apple’s 2021 Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC).

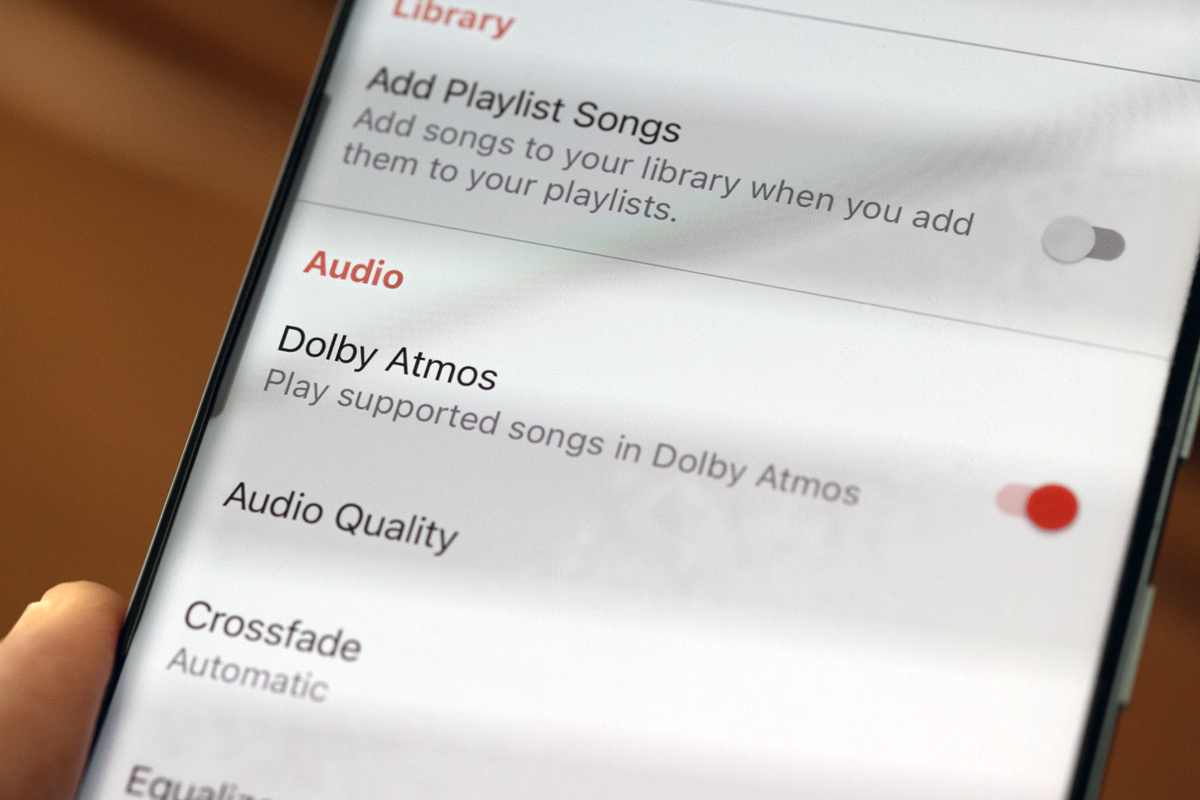

Significantly, Apple does not charge extra for lossless or hi-rez audio, or for Dolby Atmos–encoded spatial-audio tracks, which were also added to the service on June 7, 2021. Had Spotify been planning to charge a premium for lossless audio, only to be caught off guard by Apple? We’ll never know.

But there are bigger questions. Will Spotify follow through on its promise to offer lossless music? If so, when? It could happen very soon.

On January 12, Spotify announced that its second Stream On event would be held on March 8, 2023. Maybe that’s when we’ll learn more about Spotify’s plans for lossless and hi-rez music—and maybe spatial audio as well.

But maybe not. The announcement contained no information about Spotify HiFi: “During Stream On, we’ll share how Spotify is unlocking new possibilities for more creators than ever before so they can better connect with and build a truly global audience. . . . We’ll also share the latest developments and tools to help more creators chart their pathways to success, get discovered by new audiences, build an engaged community, and connect with fans worldwide.”

The fact that this teaser does not mention Spotify HiFi doesn’t dissuade me. I doubt that Spotify wanted to draw attention to the long-delayed launch of its lossless service. It would not surprise me if Spotify announced launch plans during Stream On 2023.

If that happens, here are some things I’d like to know. Is this a worldwide launch, or will Spotify HiFi be rolled out in select markets? Will Spotify’s entire catalog be available in lossless format? Will Spotify offer hi-rez audio? Or spatial audio? Will Spotify charge extra for its HiFi tier? Or will it follow Apple’s lead and offer its HiFi service at no extra charge?

There’s another reason I expect Spotify to launch its HiFi service soon; but first, some technical background.

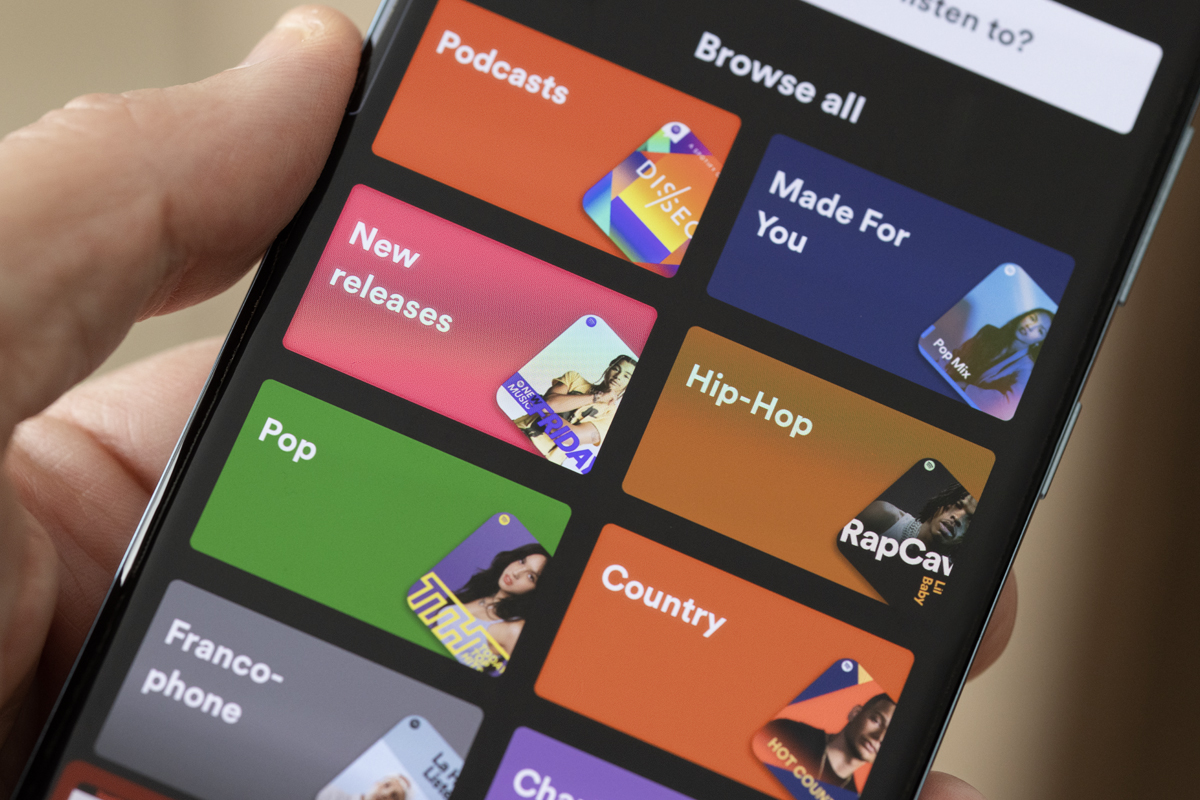

Except for Sonos, which has in-app support for Spotify, all streaming devices that support Spotify do so via Spotify Connect. After choosing the music you want in the Spotify app on a smart device or personal computer, you tap the Devices Available icon in the Now Playing screen. The app will show a list of components on your network that support Spotify Connect. Choose the one you want, and playback will transfer to that component.

This playback strategy has several advantages. For one thing, once you transfer playback to the Spotify Connect device, audio is no longer flowing to the device running the app, so you’re not drawing down the battery. It’s functioning just as a controller. More important, it means you can use the same app and device for playing through headphones when you’re out and about, and for playing music through your hi-fi when you’re at home. And you have access to all of the features available in the Spotify app, rather than a reduced set of features in a component manufacturer’s app.

I’ve spoken to many manufacturers whose streaming components support Spotify Connect. They’ve all told me that they’ll be able to support Spotify HiFi as soon as the service goes live. That’s why I believe it’s going to happen this year, with details coming at the Stream On event on March 8. But regardless of when Spotify launches its HiFi service, it’ll come way later than promised.

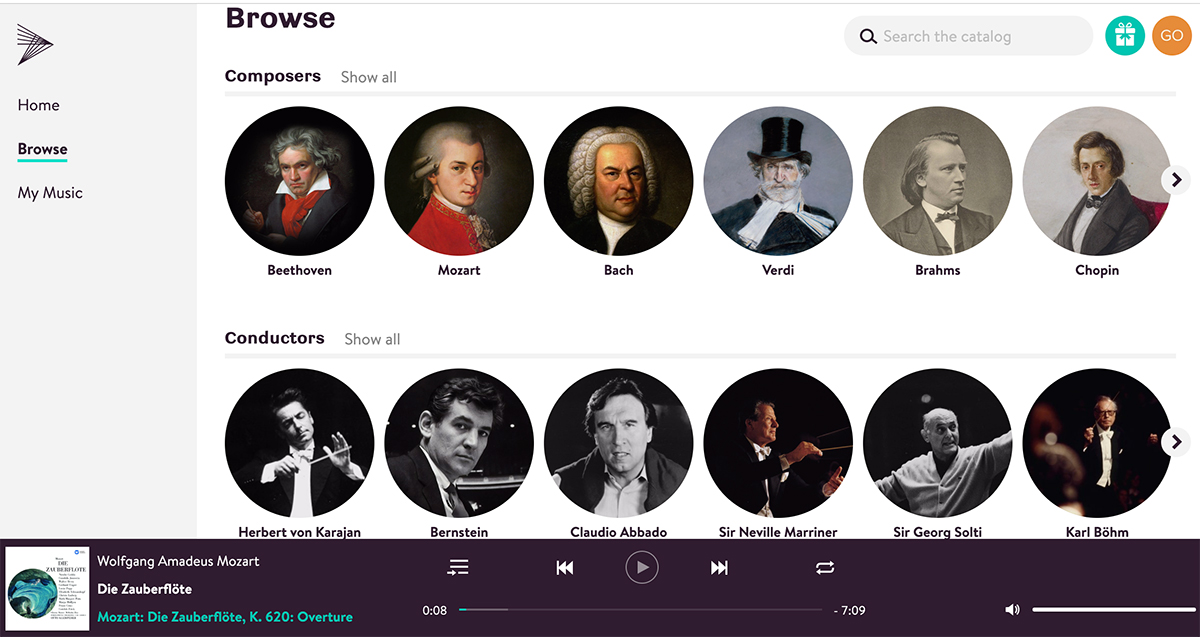

Apple streams the classics

Apple Music is also late in launching a promised service. On August 30, 2021, Apple purchased Amsterdam-based Primephonic, a streaming service that specializes in classical music. Apple pulled the plug on Primephonic on September 7, but offered Primephonic subscribers six months of access to Apple Music at no charge.

“In the coming months, Apple Music Classical fans will get a dedicated experience with the best features of Primephonic, including better browsing and search capabilities by composer and by repertoire, detailed displays of classical-music metadata, plus new features and benefits,” Apple promised. “Apple Music plans to launch a dedicated classical-music app next year combining Primephonic’s classical user interface that fans have grown to love with more added features.”

A year and a half later, there’s no sign of this “dedicated classical-music app.” What gives? To answer that question, we need to understand the unique needs of classical listeners.

As I outlined in a September 2019 feature, streaming services typically rely on metadata provided by the record label to identify content for subscribers. That metadata includes three primary fields: track name, album name, and artist name. “Our subscribers are asking for much more metadata than this, some of which the labels have, and some of which they don’t,” said Thomas Steffens when I interviewed him in 2019. Steffens was CEO of Primephonic until its acquisition by Apple.

For example, a concerto will always feature one or more instrumental soloists, an orchestra, and a conductor. An opera will have several soloists, one or more choruses, an orchestra, a choral master, and a conductor. Listeners may also want to know about the staging of the opera—when and where it was recorded, and by what opera company. In all cases, they need to know the name of the composer. Many soloists and conductors record the same work more than once during their careers, with interpretations that evolve over time, so listeners also want to know the recording date.

In addition to the metadata being complete, classical listeners need it to be consistent. Labels follow different conventions for identifying music. Some list composers by first name (or initials), others by last name. Some provide English titles (or titles in the local language of the listener) for the work; others use the original names. For J.S. Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, one label might give the composer’s name as J.S. Bach, another as Johann Sebastian Bach, and another simply as Bach. One label might list the work as Christmas Oratorio, and another as Weihnachtsoratorium. Some will list the composer’s name before the name or the work, but others will use the name of the work as the album title. If you’re looking for a specific performance of a specific work, this can make it challenging to find what you’re looking for.

To avoid this pitfall, Primephonic created a database of musical compositions that it used as the basis for editing metadata. “We have built a database of the complete output of the most-recorded 2000 composers,” Steffens told me. That database enables subscribers to search for music by composer, conductor, ensemble, soloist, period, and genre, then dig down more deeply, sorting results alphabetically or by popularity.

I’m sure this bespoke database was a big part of the value Apple saw in Primephonic. But a database like this isn’t a complete project; it’s a work in progress. If a label issues a recording of a work by an obscure composer or a premiere recording of a piece by a contemporary composer, new database entries that conform to the service’s naming conventions must be created. With every new classical recording added to the service, metadata supplied by the label must be edited, substituting the name the label has given the work for the name in the database, and supplementing the metadata provided by the label.

Another attraction of a specialized service like Primephonic is the provision of discovery tools such as curated playlists. When it was operating, Primephonic had playlists for different moods, different composers, different genres and instruments, music from different nations, key masterworks, obscure works of well-known composers, and thematic playlists. Listeners new to classical music could use them to explore the genre. Primephonic had a team of ten musicologists editing metadata and creating playlists. Apple will have to do likewise if it wants to create a service that appeals to classical listeners.

Primephonic’s home page displays a short notice, dated August 30, 2021, announcing the cessation of the service and the acquisition by Apple. “As a classical-only startup,” the notice reads in part, “we cannot reach the majority of global classical listeners, especially those that listen to many other music genres as well. We therefore concluded that in order to achieve our mission, we need to partner with a leading streaming service that encompasses all music genres and also shares our love for classical music.”

That doesn’t mean Apple will merge classical with other genres under a single interface. Note Apple Music’s announcement that it “plans to launch a dedicated classical-music app.” But will Apple charge classical listeners extra for this “dedicated experience,” or will it be available to all Apple Music subscribers? And when will Apple Music deliver this “dedicated experience?”

Classical music may be a niche market, but it’s an important one. Classical listeners consume a lot of music, and they tend to listen intently. It’s a challenging genre to reproduce, so most classical listeners are particular about their playback systems. Apple clearly acknowledges the importance of this audience, as evidenced by its acquisition of Primephonic. Just as tellingly, Apple is a major sponsor of the Gramophone Classical Music Awards, and the key sponsor of the UK classical-music magazine’s spatial-audio award category.

Simplifying Atmos

Since launching spatial audio in mid-2021, Apple has made some important hardware and software announcements around the technology.

Announced at last year’s WWDC and released on September 12, 2022, iOS 16 has a feature called Personalized Spatial Audio. It customizes the way spatial-audio tracks are rendered for individual listeners.

First, some background. People perceive where sounds are coming from based on when they arrive at each ear, and by the way sounds are filtered by the shapes of their heads and their ears. For listening to Atmos tracks through headphones, the playback device (an iPhone in this case) applies filters and interaural delays that mimic the cues we use to perceive sound direction in real life; this is called a head-related transfer function (HRTF).

Most playback devices use a generic HRTF to render Atmos streams for playback through headphones. With the advent of iOS 16, owners of iPhones with True Depth cameras (iPhone X and later) can create a custom HRTF by scanning their heads and ears with their phone cameras. The feature only works with select Apple headphones: AirPods Pro (1st or 2nd generation), AirPods Max, AirPods (3rd generation), and Beats Fit Pro.

At a launch event on January 18, Apple announced several new products, including one that makes it simple to listen to Dolby Atmos tracks out loud. Equipped with a 4″ long-excursion woofer and five beam-forming tweeters, Apple’s new HomePod smart speaker has a whole slew of intriguing features. It can sense the acoustic characteristics of the listening environment and adjust bass output accordingly. Two HomePods can be paired for stereo. Listeners can hand off playback of music from an iPhone to the HomePod(s), or vice versa. A HomePod, or better still a pair of HomePods, can deliver Dolby Atmos immersive audio when paired with an Apple TV 4K media adapter. And they can play Dolby Atmos spatial-audio tracks (and lossless and hi-rez tracks as well) from Apple Music.

If Apple’s goal with spatial audio and hi-rez music is to drive subscription revenue, and not just hardware sales, it would make sense to improve the way streams from Apple Music are delivered to third-party products. If you have an Atmos soundbar or A/V receiver, you can play spatial audio if it’s connected via HDMI eARC to a recent TV running the Apple Music app, or to an Apple TV 4K. But it would be simpler if you could cue up some spatial-audio tracks on an i-device, and then shoot them over your home network to a Dolby Atmos soundbar or A/V receiver. That would provide simplicity of operation comparable to playing spatial audio through the new HomePod. Likewise, it’d be nice if two-channel listeners could send hi-rez audio from an i-device to a music system via Wi-Fi.

Apple uses Ultra Wideband technology to hand off playback from iPhones to HomePods. But UWB isn’t available on third-party soundbars and A/V receivers. So this kind of functionality would probably require an enhanced version of AirPlay. For hi-rez streaming, that would mean going beyond 16/44.1 for audio-only streams, and 16/48 for TV audio. For spatial audio, it would mean enabling AirPlay to carry Dolby Digital+ streams, which is a taller order than just adding hi-rez support. Might we hear something about AirPlay 3 later this year—maybe at WWDC? I wouldn’t bet more than a dime on this, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it happened.

Tidal also offers Atmos–encoded music. You can listen to this content through headphones connected to a smart device running the Tidal app. For out-loud listening, you can play Atmos tracks using the Tidal app on supported media adapters. These include the Apple TV 4K, recent models of Amazon’s Fire TV Stick, and recent models of Nvidia’s Shield TV. You can also play Atmos tracks using the Tidal app on Atmos-enabled Android TVs from Sony and Philips.

But there are scores of Atmos A/V receivers and soundbars with built-in streamers and companion apps that have integrated support for Tidal. You can use these apps to stream two-channel content from Tidal, but not Atmos-encoded content. There are many possible explanations for this.

To add support for Tidal’s Atmos content, receiver and soundbar manufacturers have to update their streaming apps, and possibly the component firmware as well. Manufacturers are understandably reluctant to invest money in writing and debugging new code unless there is a clear business case for it. Is the ability to access Tidal’s Atmos content a deal-clincher for people purchasing these products? I doubt it.

There may be technical barriers as well. For A/V receiver and soundbar manufacturers to enable access to Tidal’s Atmos content, Tidal has to provide appropriate development tools. And of course, Tidal has to actually stream Atmos audio to the component when a listener requests an Atmos track.

What about Tidal Connect? Tidal Connect works much like Spotify Connect. It lets users cue up music in the Tidal app on a smart device or personal computer, and then transfer playback to a component that supports Tidal Connect. Some Atmos A/V receivers and soundbars have this feature. But currently, Tidal Connect only sends a two-channel stream to Atmos-enabled components. For Tidal to send an Atmos stream via Tidal Connect, the service would have to recognize that the destination component could decode the stream, and the component would have to recognize that it was receiving an Atmos stream.

Clearly, there’s a lot Tidal could do to make it easier for owners of Atmos components with streaming capability to access its Atmos content. It’s anyone’s guess as to whether any of this will happen—in 2023 or beyond.

Spatial audio probably isn’t a big deal for people who have full-blown home-theater setups—these folks are mainly interested in movies. But for music-lovers with an Atmos soundbar or a pair of Atmos-capable smart speakers, it’s potentially a very big deal, because Atmos can help transcend the physical limitations of setups like these.

I’m sure the vast majority of SoundStage! readers listen to two-channel. And the fact is, two-channel streaming is a mature technology. In 2023, we’re living in a music-lovers’ paradise.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse