Is classical music in danger of dying “a digital death”? That prospect worries Thomas Steffens, CEO of Amsterdam-based Primephonic, a streaming service that specializes in classical music. “The world is moving toward streaming, where there are no CD stores anymore, and download stores are disappearing,” Steffens told me in an interview. “At the same time, classical music is massively underrepresented on streaming services. Classical music accounts for 5% of all global music consumption, but only 1% of streaming music, and 0.5% of streaming royalties.”

That concern led Steffens to leave his position at Boston Consulting Group in 2017 and, with two like-minded partners, form Primephonic. The service is now available in 161 countries, the main exceptions being China, Japan, and Russia. Steffens said that Primephonic has a catalog of approximately two million tracks, all available in 16-bit lossless format, and some in 24-bit hi-rez.

Thomas Steffens

Thomas Steffens

Primephonic streams in MP3 at 320kbps on its Premium tier, which costs $7.99/month or $79.99/year (all prices USD). For lossless and hi-rez streaming in FLAC format, you need to subscribe to Primephonic’s Platinum tier ($14.99/month or $149.99/year).

Primephonic wasn’t first out of the gate with a classical-only streaming service. That distinction belongs to Berlin-based Idagio, which has users in 190 countries (it’s not available in China and Japan). Idagio charges $9.99/month for full access to its catalog of two million tracks. Users can stream 16-bit lossless FLACs, or MP3s at 192 or 320kbps.

Idagio was founded by Till Janczukowicz, who has a background in classical artist management and orchestral tours. “Till believed that if you’re not present in the streaming world, with a really good product for classical music, people will gradually stop listening to classical,” said Idagio CEO Christoph Lange, who previously operated another streaming service, became a partner in Idagio in 2015, and whom I also interviewed. “That’s an existential threat to the genre and the ecosystem. Classical cannot be represented well enough by Spotify and the other large streaming services, because ultimately, they don’t really care about classical.”

Details, details

As Steffens and Lange both pointed out, the major streaming services use metadata supplied by record labels to identify content in three primary fields: artist, track title, and album title. “Our subscribers are asking for much more metadata than this, some of which the labels have, and some of which they don’t,” Steffens told me. “I have ten musicologists on my team who on a daily basis are completing and correcting this metadata.”

Christoph Lange

Christoph Lange

“A music-streaming service for classical has to be built differently than a pop-music service,” added Idagio’s Lange. “Artist, title, and track information is not enough. You have to start with the foundational layer, which is the metadata that is coming with the music. We have a team that manually edits all the metadata that we get.”

Along with completeness, another problem with relying on record labels for metadata is consistency. You can search a streaming service for a specific work, but the search results will often be incomplete because the service doesn’t follow consistent naming conventions.

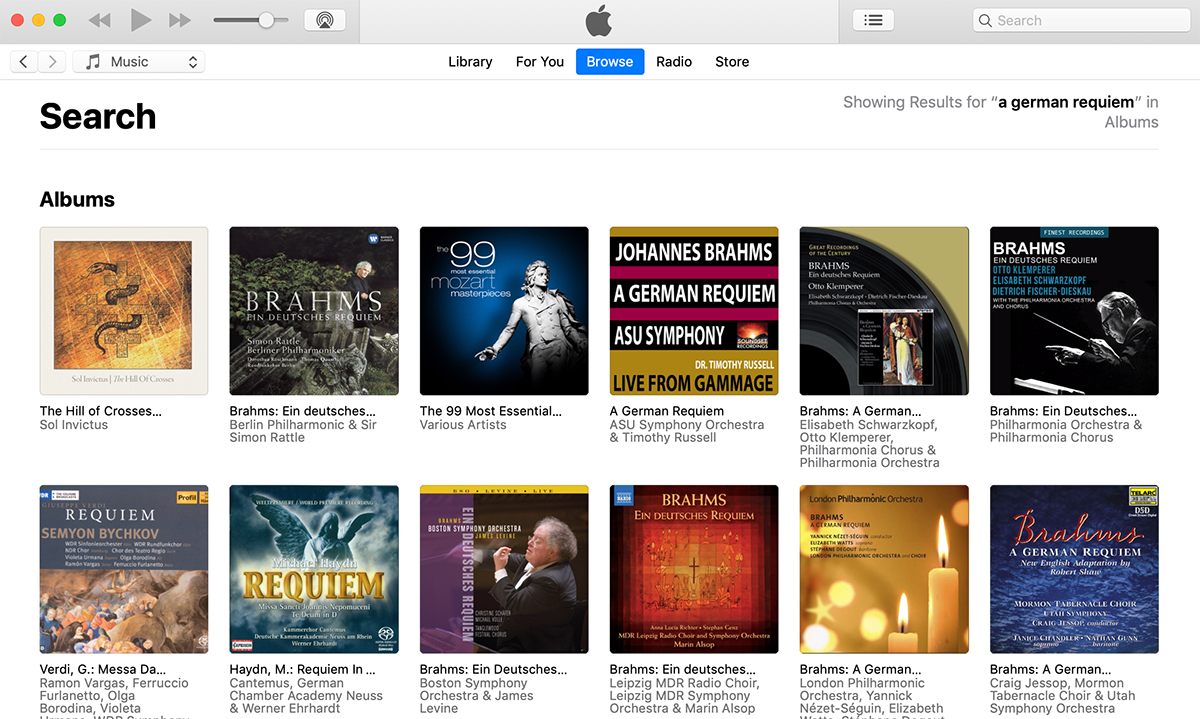

An example: Let’s say you want to hear Johannes Brahms’s choral masterpiece Ein deutsches Requiem. With Tidal and Apple Music, I got one set of results when I searched for “Ein deutsches Requiem” and a completely different set when I searched the work’s title in English: “A German Requiem.” Apple Music added another layer or weirdness -- when I searched for “A German Requiem” on Apple, the top hit was an album called The Hill of Crosses by Sol Invictus, and the third hit was a collection called Mozart Masterpieces. Apple’s search results for “Ein deutsches Requiem” were even stranger: Only two albums were listed, the first being Hybris, by Deadlock.

To avoid this pitfall, Idagio and Primephonic have created databases of musical compositions, which they use as the basis for editing metadata. “We have built a database of the complete output of the most-recorded 2000 composers,” said Steffens of Primephonic. For customizing its metadata, Idagio uses a database it calls a “work catalog.” “We have about 160,000 works in our catalog, which we manually put together with our editors,” Lange explained. “To our knowledge, it’s the largest work catalog available. Then we marry the work information with the recording information, and update and enrich what we get from the label.”

With their bespoke databases, Primephonic and Idagio can apply consistent naming conventions to classical works such as Brahms’s Ein deutsches Requiem, which makes it much easier for listeners to find the music they want to hear, and to compare different versions of the same work. The same applies to performers and ensembles. For example, both services consistently use “Berliner Philharmoniker,” not the orchestra’s name as translated into English, “Berlin Philharmonic” -- instead of the German name for some releases and the English name for others.

Browsing for music

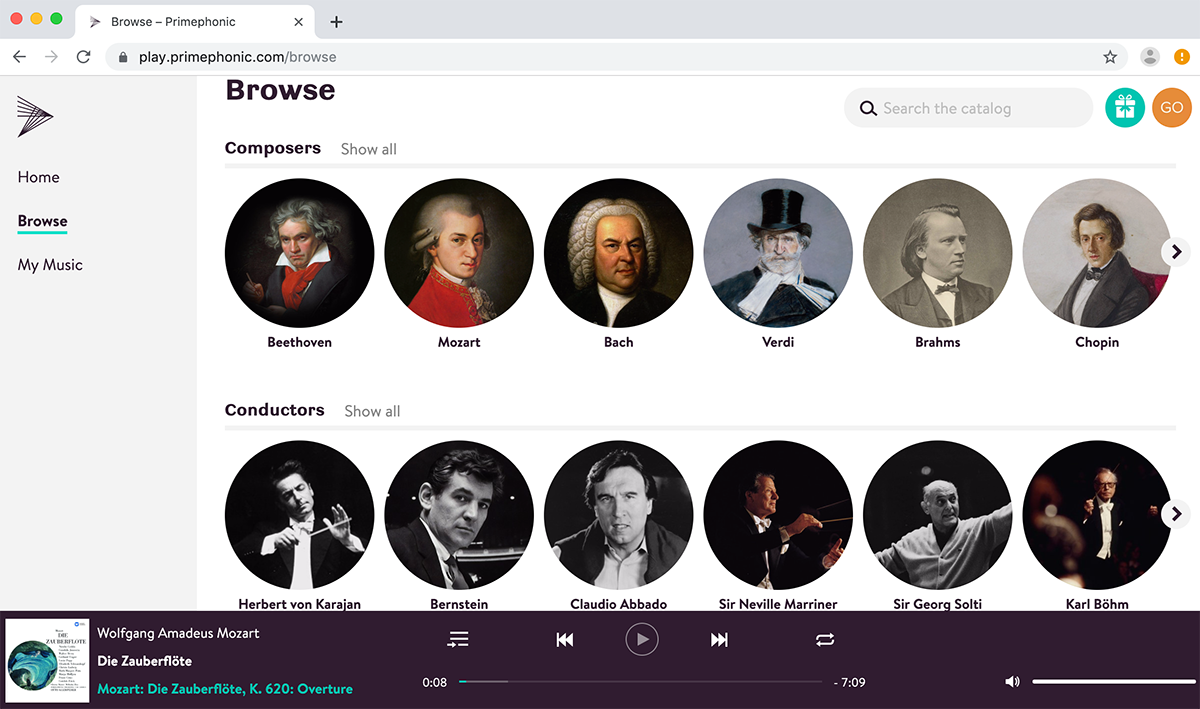

Idagio’s and Primephonic’s customized databases enable users to browse the services’ catalogs in a way that would be impossible with generic music services that rely on record labels for metadata.

With Primephonic, choosing the Browse function in the main menu takes you to a window where you can search for music by Composer, Conductor, Ensemble, Soloist, Period, and Genre, then dig down more deeply, sorting results alphabetically or by Popularity. It’s a fantastic tool that makes it easy to explore all available performances of a specific work.

But it’s not perfect. One annoyance is that Primephonic sorts performers by first rather than last name -- you’ll find Leonard Bernstein under L, not B.

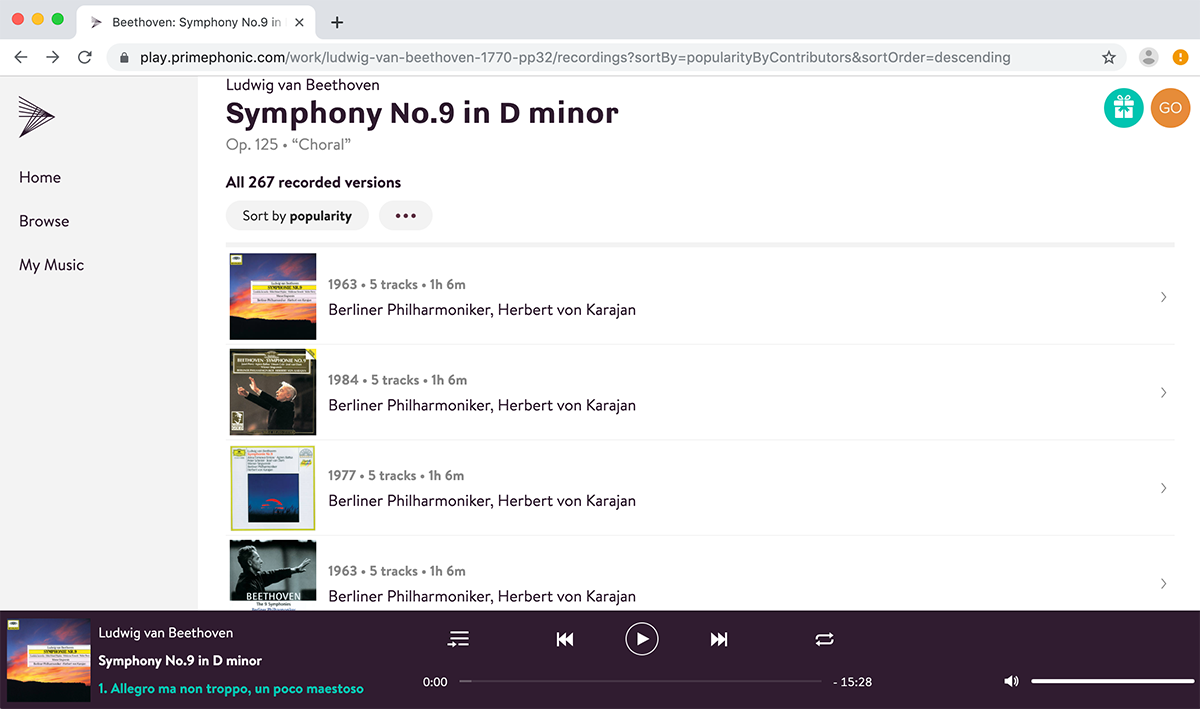

Primephonic often lists multiple versions of the same recording -- reissues made at different times of the same performance. Sometimes the listings show the release date of the album, which in the case of a reissue is of limited use. What most classical listeners want to know is the date of the original recording.

Here’s one example. Primephonic offers 299 different recordings of Beethoven's Symphony No.9. Sorting by popularity, the first five entries are stereo recordings on Deutsche Grammophon by the Berliner Philharmoniker under the direction of Herbert von Karajan. The first three of these correctly show the recording dates (1963, 1984, 1977). The fourth entry is actually for Karajan’s entire 1963 Beethoven cycle. The fifth gives a date of 2014 -- by which time HvK had been pushing up daisies for a quarter century. This entry is for a reissue of Karajan’s 1963 Beethoven Ninth, released to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the conductor’s death. Further down the list is a stereo version of a Ninth that Karajan recorded in 1955 with the Philharmonia Orchestra for EMI (now Warner Classics). For that version, the only artist listed is Herbert von Karajan -- no mention of orchestra, chorus, or soloists, and no recording date.

If you’re not into classical, these details may seem trivial, but to serious classical listeners they’re really important. Karajan’s approach to the Ninth evolved over his lifetime, and these recordings reflect that journey.

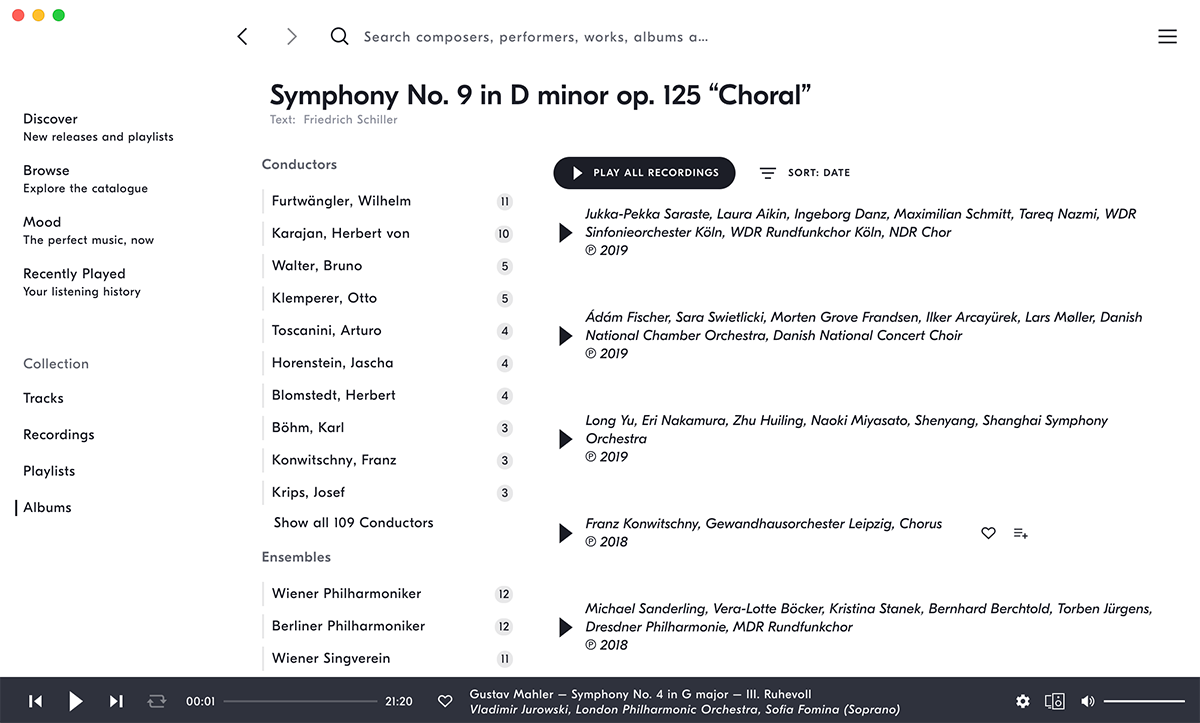

The Browse function in Idagio’s macOS app is even richer. The main Browse menu lets you sort by Composer, Performer, Period, Genre, and Instrument. Within all of these fields you can further narrow your search. Under Performers, for example, you can view Conductors, Pianists, Violinists, Cellists, Vocalists, Ensembles, and Period-Instrument Ensembles.

If you’re browsing by Composer, you can view Albums, Works, or Recordings, sorting results alphabetically or by Popularity. Choose a Work, and you can view results alphabetically, or by Popularity or Release Date. The mobile app, however, lets you sort only alphabetically -- you may have to do a lot of scrolling to find what you want.

I used the Browse feature in Idagio’s macOS app to check out recordings of Beethoven’s Ninth. To the left of the list of recordings was a menu that let me choose recordings by specific Conductors or Orchestras. As with Primephonic, some of the listings of performances by Herbert von Karajan had dates that corresponded to a reissue rather than to the original recording date. But there didn’t seem to be multiple releases of the same performance. A welcome touch was the inclusion of the recording venue for many recordings. And I appreciated the fact that Idagio sorts performers by surname rather than by given name.

Let’s keep my criticisms in perspective: What Idagio and Primephonic are doing is infinitely better than anything offered by the major streaming services. Not only do they provide a way of viewing the output of all major composers, and all the recordings they offer of a given work, they do so in a consistent, predictable manner.

Discovering music

Browsing is wonderful for music you know you want to hear, but the great thing about streaming is how it lets you discover new music. On their home screens, Idagio and Primephonic have a variety of discovery tools.

Prominently displayed on both services are new album releases. Lower in its Discover screen, Idagio breaks out new releases into various genres: Orchestral, Concerto, Chamber Music, Instrumental, Choral, Opera, etc. Idagio also has a category for Award-Winning Albums, and another for winners of the German Record Critics Award. Primephonic does not display new releases with this level of granularity.

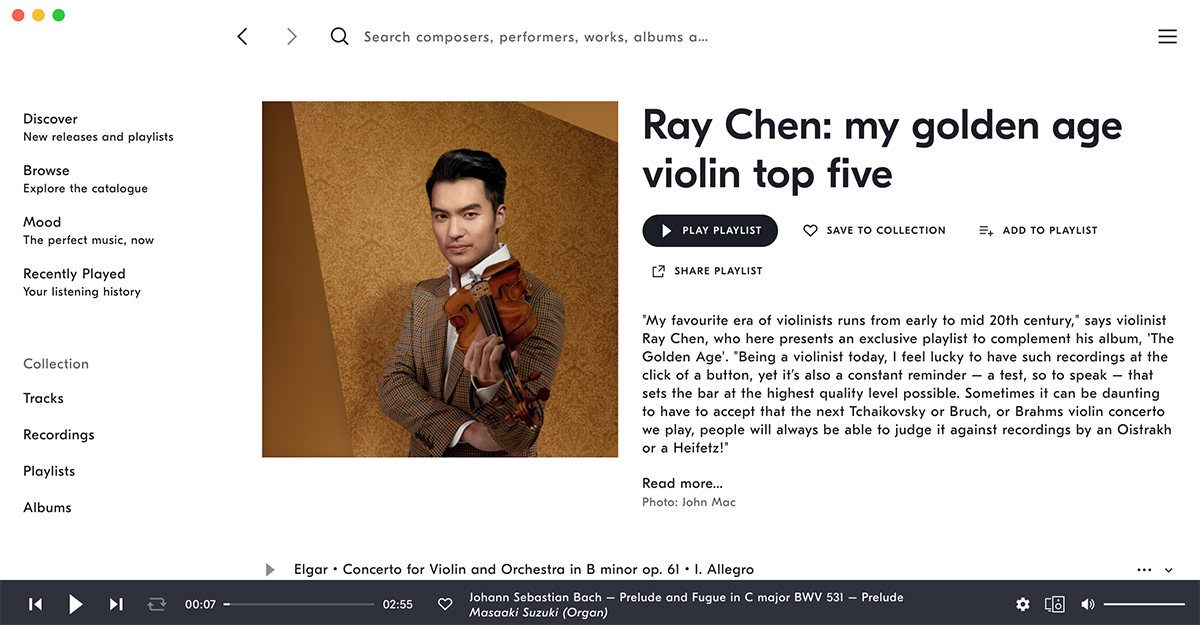

Both services offer playlists from guest artists, journalists, and in-house curators. Helpfully, Idagio’s playlists include compilers’ comments on the playlist’s contents. “We believe it’s really important for a genre like classical and a service like Idagio to have really strong human curation,” Lange said. “We have our own editorial team who provide playlists and recommendations, and we have a network of people from the classical music world -- critics, journalists, artists -- contributing playlists and giving recommendations.

“Because we have clean metadata, we can offer better automated recommendations,” Lange continued. “We have launched the world’s first work-based recommendation system for classical music. Services like Spotify work on a track-based system -- this track is similar to that track. For classical music, that doesn’t make sense. You want to be recommended the next work that makes sense. In the next few months, we’re going to add automated recommendations that make use of our metadata that sit on top of our human curation.”

Playlists are a real strength for Primephonic. On its home screen are playlists for new listeners, and playlists for different moods, different composers, different genres and instruments, music from different nations, key masterworks, obscure works of well-known composers, and thematic playlists. I spent several pleasantly unproductive hours exploring these lists. I particularly enjoyed a playlist of music for prepared piano, for which the performer has altered the piano’s sound by inserting in the instrument such objects as screws, rubber, and paper.

As Steffens observed, features like playlists can help all classical listeners broaden their musical horizons: “The classical music canon has a few hundred thousand works. If you really know a lot about classical music, you may know 20,000 works. We can introduce people to music they don’t know yet.”

Hardware and software

An important question about any streaming service is the range of devices that can be used for playback. Not surprisingly, the choices for Primephonic and Idagio are more restricted than they are for major services like Spotify and Apple Music.

Idagio and Primephonic both have player apps for iOS and Android -- plug in a set of headphones and you’re ready to go. On Windows PCs and Macs, Primephonic plays from your Web browser. Idagio has an app for macOS, but for Windows, it plays from a Web browser. For playback from a computer, Idagio and Primephonic both route audio through the operating system, so if you’re using a USB DAC connected to a PC or Mac, you’ll have to enable the DAC in your OS.

Both services support Apple AirPlay. Listeners can stream from an iOS device or Mac to any AirPlay-capable component via Wi-Fi. Idagio also supports Chromecast, allowing users to stream from iOS and Android devices to any component with Chromecast Built-in, or to a Chromecast dongle.

In addition, Idagio is one of the many streaming services fully supported within the Sonos app. Lange told me that full Bluesound support is “very close.”

Steffens said that Primephonic hopes to offer direct Sonos integration “within two months.” Chromecast capability will be implemented “hopefully by the end of the year,” he added, and Bluesound integration is “on the radar.” In the meantime, you can use AirPlay to stream Primephonic to Sonos and Bluesound hardware via Wi-Fi. Roon integration is also in the works, and could happen by year’s end, Steffens said.

One other note: Primephonic offers 24-bit content, and shows the Hi-Res Audio logo on the splash screen of its mobile apps. But with the Web player on my MacBook Pro, the Android app on my LG G7 ThinQ smartphone, and the iOS app on my iPad Mini, I could find no way of determining which albums were offered in hi-rez. During playback, there was no indication of resolution. Moreover, if the playback app relies on the device’s OS for audio playback, there’s no assurance that that device won’t downsample hi-rez content.

Hi-rez content will definitely be downsampled to 16/44.1 or 16/48 when streamed via AirPlay -- or to Sonos, when Primephonic begins offering Sonos integration. But hi-rez streaming should be available when support for Bluesound, Chromecast, and Roon arrives.

A third possibility

There are lots of people, me included, whose primary musical interest is classical but who also listen to other genres. For some of these people, it may make sense to subscribe to Primephonic or Idagio for their classical listening, and another service for other genres. Before making that decision, though, they may want to consider the French streaming service Qobuz, which last year expanded into the US.

Dan Mackta

Dan Mackta

“In terms of time spent streaming, classical is our third-most-popular genre, behind rock and jazz, but ahead of hip-hop, folk, R&B, and all the other top-level genres on Qobuz,” said Dan Mackta, managing director of Qobuz USA. “The company was started by classical-music fanatics in France, and originally, it was classical only.”

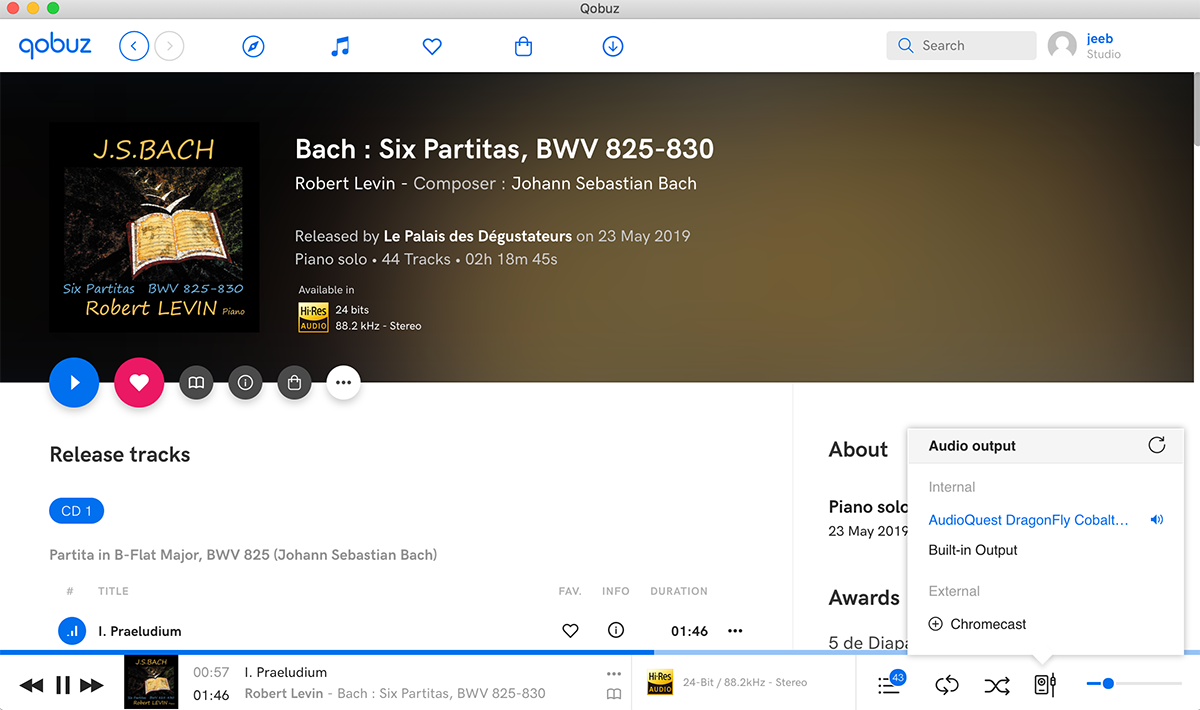

In the US, Qobuz’s least expensive tier, Premium, costs $9.99/month or $99.99/year, for streaming in MP3 at 320kbps. Its Studio plan, which offers unlimited lossless and hi-rez streaming, costs $24.99/month or $249.99/year.

The service has very capable apps for iOS, Android, macOS, and Windows. The desktop apps have their own playback engines, so you can play to a USB DAC without going through operating-system menus. Moreover, the app will play hi-rez content at the correct bit depth and sample rate.

Qobuz playback is also integrated into Roon music-management software, and into many hardware systems, including Sonos and Bluesound. In terms of hardware and software support, at this point Qobuz is well ahead of Idagio and Primephonic.

Mackta conceded that Idagio and Primephonic do a better job of adapting metadata to the needs of classical listeners. Qobuz uses the metadata supplied by record labels. As a result, search results can be fragmented. As happened on Tidal and Apple Music, searching for Ein deutsches Requiem and A German Requiem on Qobuz yielded different sets of results, including one very weird entry for the latter search: Boom Boom Boom Boom: Europop by Audio Idols.

More important, the lack of standardized, customized metadata makes it impossible for Qobuz to offer a browse feature comparable to those in Idagio and Primephonic -- a very big deal for classical devotees.

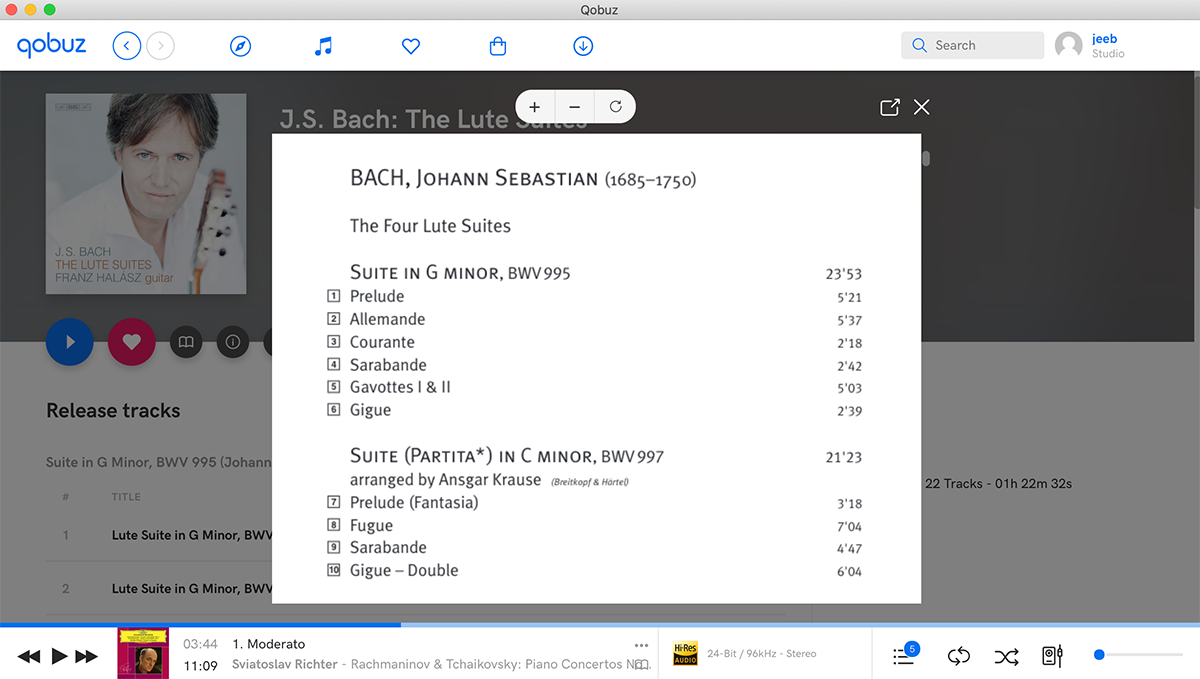

But, as Mackta noted, Qobuz offers some great features that Idagio and Primephonic don’t. A big one is liner notes, which I find very valuable. If these are available, you’ll see a booklet icon below the album cover. Click it, and the booklet appears onscreen. This feature is also available when you use Roon to stream from Qobuz. “For classical, this feature is really appreciated by our users," Mackta said. “It’s a bit of a hybrid of old school and new school. It’s up to the labels to provide the booklet, and we’re chasing them all the time.”

Qobuz also lets listeners view complete track metadata, by clicking the information icon in the track listing. “A listener can click down on a track level, and see all of the metadata that’s been supplied by the label,” Mackta explained. “Everything that we get, we can show -- composer, conductor, main artist, soloist, producer, recording engineer, mastering engineer -- it’s all in there if the label has supplied it.” That option is not available on Idagio or Primephonic.

I find Qobuz’s editorial content and discovery tools comparable to Primephonic’s and Idagio’s, and in some respects superior. Many new releases have reviews or commentary by Qobuz’s in-house writers. Qobuz also offers what it calls Panoramas -- essays on composers, major works, conductors, and musical genres, with links to representative albums.

Another Qobuz feature I really like is Press Awards, which includes albums named as Editor’s Choices by Gramophone magazine.

Qobuz also has a broad catalog of hi-rez content. And, as Mackta told me, it runs a download store: If you hear an album you really want to own, you can buy it on Qobuz.

Supporting the genre

Idagio and Primephonic differ from other streaming services, including Qobuz, in how they pay royalties. At mainstream services, the payout to labels is based on track count. Primephonic and Idagio use a per-second model for payout. “With Spotify or Apple Music, a three-minute pop song counts the same as a 25-minute movement from a Mahler symphony,” Lange explained. “We think this is unfair.”

Steffens said that the track-count model is affecting how classical music is being recorded, formatted, even composed. “Some artists now prefer to record shorter works,” he explained. “You can see labels cutting classical works into pieces. I’ve even heard that some contemporary composers are being incentivized to compose shorter works. We want labels, artists, and composers to create music with artistic hearts.”

Is there room for two streaming services devoted to classical music? Steffens thinks there is, and that Primephonic and Idagio have important roles to play in our musical future. “Of course we are competitors, but we share the same mission,” he said. “We are both trying to save classical music from a digital death. We want to keep classical music alive for a streaming generation.”

. . . Gordon Brockhouse