If anyone made a list of the 21st century’s most successful hi-fi speakers, that list would surely include the KEF LS50, introduced in 2012 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the BBC LS3/5a minimonitor. Since then the LS50 has received countless honors, including Reviewers’ Choice and Product of the Year awards from SoundStage!.

In 2017, KEF introduced a wireless active version of the LS50. Like its passive cousin before it, the LS50 Wireless won Reviewers’ Choice and Product of the Year awards from SoundStage!. Last year, KEF introduced a smaller, lower-cost active speaker, the LSX, which I recently reviewed for SoundStage! Simplifi.

More than any other product I can think of, the LS50W has legitimized for audiophiles the idea of an active loudspeaker -- it shows what can be accomplished when you make a great passive speaker active.

The process was very instructive, says Jack Oclee-Brown, KEF’s head of acoustics, but not at all straightforward. As Oclee-Brown explains below, implementing the LS50W’s active crossover filters involved a lot of “learning on the job.”

In this third of our series of interviews with designers of active and powered loudspeakers, Oclee-Brown explains the engineering decisions made in the design of the LS50W and LSX, including the digital signal processing (DSP) circuits that handle the crossovers, phase correction, room correction, and distortion reduction. He also discusses how the lessons KEF has learned from these products could be applied to future, more ambitious designs.

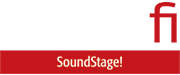

Gordon Brockhouse and Jack Oclee-Brown at High End 2019

Gordon Brockhouse and Jack Oclee-Brown at High End 2019

Gordon Brockhouse: Given the advantages of active speakers, I’m surprised they haven’t caught on among audiophiles. What’s your take on this?

Jack Oclee-Brown: Active speakers are pretty much the norm in pro audio and PA [public address systems]. Technically, there’s no reason why they shouldn’t have caught on in audiophile circles. But there are some nontechnical reasons.

Our customer is the system builder. At the high end, our customers aren’t looking at an audio system as this year’s purchase and a car as next year’s. Somebody who’s passionate about hi-fi has built up their system over a number of years. As they do that, they’re probably thinking about next year’s purchase, and the year after that.

Retail infrastructure is built around the idea of the return customer. In the past, active speakers might not have been sold as enthusiastically as conventional passive speakers.

GB: Do you think active speakers are gaining more acceptance?

JO-B: Yes, for a couple of reasons. One is computer audio. Once you no longer have to change discs or interact with your system physically, your relationship with the equipment becomes a little different. More people are moving to streaming services, or ripping their own music. That gives you the opportunity to put everything in the speaker.

The other reason is that traditional component audio hasn’t managed to grab the attention of the up-and-coming market. The average age of a typical system builder is pretty high. But there are loads of people who are really into music who listen mainly on headphones.

At some point, people in that generation, who don’t really know what hi-fi is, will want a better system. But their expectations are totally different. They’re used to the convenience of computer audio. I don’t think this audience will accept having to have all these boxes and interconnects.

A lot of these people have bought little Bluetooth speakers, or Wi-Fi speakers from companies like Sonos. These speakers are active. Is there an appetite for something better among these listeners? If you want to know if something will work, you just have to do it. We have sold enough LS50Ws that we know there is a market for this.

We also think a lot of LS50Ws are being sold to our traditional customers. Somebody who has a high-end system in their main room might consider an active system for an office or bedroom. We also seem to be selling them to people who have drifted away from hi-fi and want to get back into it, but don’t want to build a system.

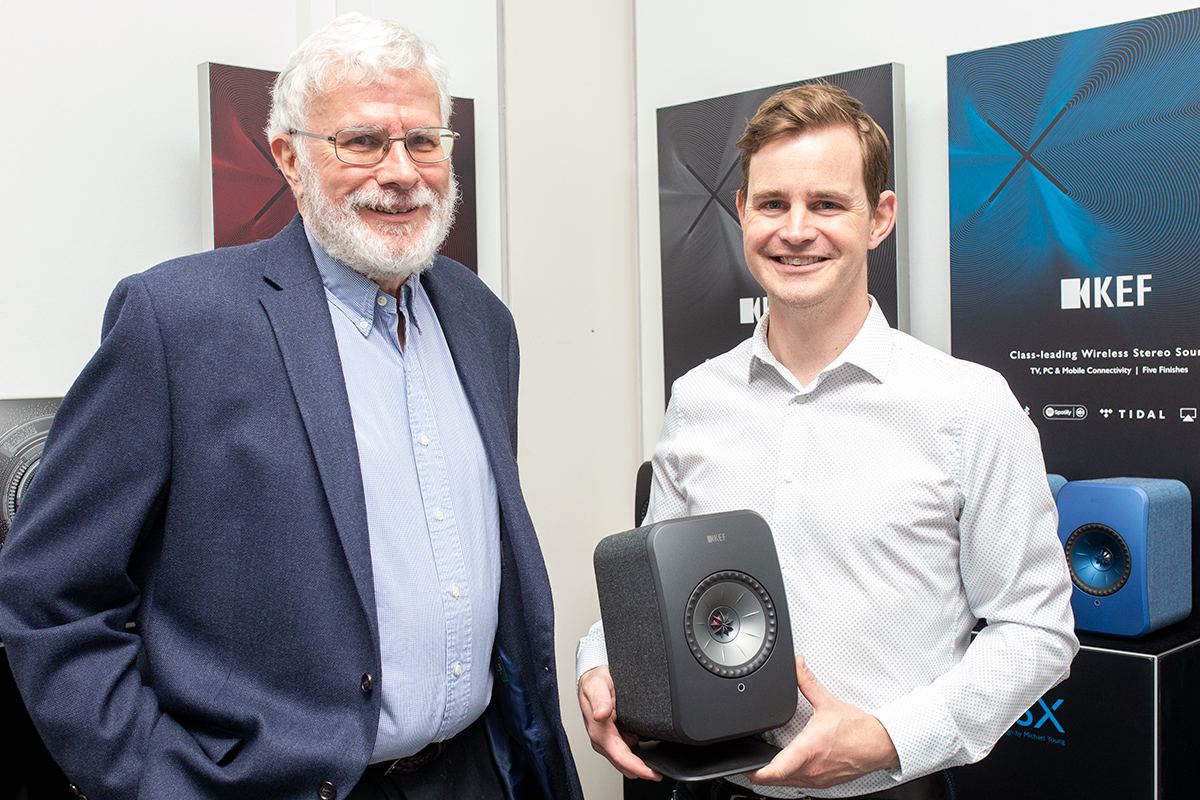

The LSX in Maroon finish

The LSX in Maroon finish

GB: There’s still a lot of resistance to active speakers among traditional audiophiles. Is there something they don’t get?

JO-B: For designing a crossover, passive is really restrictive. Adding extra components will give you more control over how you divide up the signals, but will also introduce nonlinearities and compromise signal quality. If you want to go really high-end, you have to spend a lot of money on big, low-tolerance components that are linear. We’ve designed hundreds of passive crossovers, and we like to think we’re very good at knowing the compromises.

With an active system, the compromises are different. You have a lot more flexibility in terms of the filter shapes. And you completely decouple the driver from the filter. With a passive system, the driver and filter are singing together. Also with a passive system, the driver with the lowest sensitivity sets the system sensitivity.

GB: Like almost all active speakers for home applications, the LS50W and LSX implement the crossover in digital signal processing. But some audiophiles dislike the idea of DSP, saying it has undesirable side effects. What’s your response?

JO-B: I don’t have a problem implementing a DSP crossover, providing I’m not degrading the signal. With digital sources, I’d rather implement the crossover before the DAC. The big caveat is analog sources. You don’t want to take a signal in through an ADC and back through a DAC needlessly. On the plus side, if you’re implementing the DSP properly, you don’t get additional noise or distortion as you pile up the filters. These problems can creep up with analog crossovers.

We can make the system more adaptive with DSP. We can ask users some simple questions and, based on their answers, really improve their experience of the product in their actual room. That’s particularly important with the LSX, because I think a lot of those are being sold to people who don’t know you should have a set of speaker stands, and place the speakers away from the walls.

DSP also gives us versatility in terms of internal processing. We can monitor what you’re listening to, how much you’re pushing the drivers, and then, at a very basic level, we can stop you from ever breaking your speaker. We don’t overdo this. You can compare this to anti-lock brakes -- we’re trying not to do anything until something’s going to go wrong. That would be tricky to do with analog.

The final part is stuff you can’t do any other way. We’ve implemented time-domain correction on the LSX and LS50W. When you restrict frequency bandwidth, which is what a crossover does, there’s an effect in the time domain. Typically, when you pass a signal through a low-pass filter, it gets delayed; when you apply a high-pass filter, it doesn’t. So the sound from the tweeter is the first to arrive at your ears, then the mids, and then the lows a bit later. We’re quite used to this, because every speaker most of us have ever heard behaves that way.

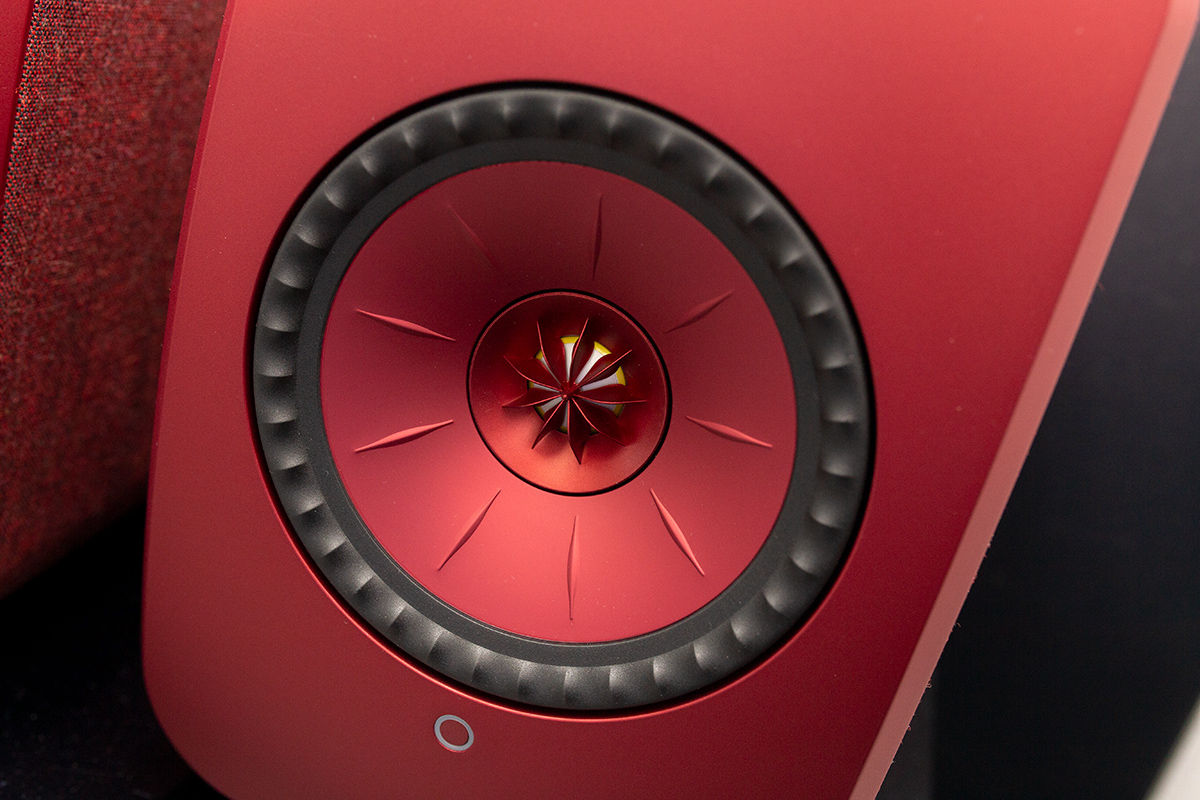

The LSX’s rear panel

The LSX’s rear panel

With DSP, you can delay the highs so they arrive at the same time as the mids. That’s what we do when you select phase correction. It’s defeatable. I haven’t come across many people who don’t like the effect, but we were worried about artifacts, or people being so used to time-domain smearing that it seemed unnatural if you took it away.

You have to be careful about this. If you don’t get time alignment between the drivers right, you could introduce artifacts that happen before the signal. Those artifacts are highly audible.

With masking, your ability to hear a quieter sound depends on how far away it is from louder sounds. With two closely spaced frequencies, you struggle to hear the quieter sound. This happens in time as well. If a quiet sound happens after a loud sound, it’s quite hard to hear. If it happens before a loud sound, it’s very audible. Because of the way normal speakers smear things in time -- they’re smeared to be later -- you can get away with artifacts. But if you do something that causes an artifact before the sound, you could be in real trouble.

Designing the filters for the LS50W was an interesting process, because we were kind of learning on the job. When we tried to design the crossover filters in the frequency domain, the speaker just sounded gritty. It took away a lot of space in recordings, and was very fatiguing. In the end, we found that we needed to optimize the filters in the time domain, to minimize artifacts before the impulse. The key thing was not doing it for one listening position.

GB: In the LS50W you have a class-D amp for the woofer and a class-AB for the tweeter. In the LSX you use class-D for both drivers. How were these decisions made, and what are your thoughts of both amplifier topologies?

JO-B: Space gets very tight in an active speaker. When we started looking at doing an active version of the LS50, we asked: If you use an LS50 with a ridiculously big amplifier, and push it as hard as you can before it’s really struggling, what are the dynamic power peaks you have to deal with? This highlighted the need for very high dynamic power on the LF. We wanted to go up to about 250W for short durations. To do that with class-AB, we would have to dissipate a lot of heat. We decided that the best compromise was class-D on the LF, but class-AB on the HF, where we don’t have that kind of dissipation.

Jack with the LS50W Nocturne Edition

Jack with the LS50W Nocturne Edition

GB: Why use class-AB on the HF unit? Why not class-D?

JO-B: Our HF signal has very short transients, so long-term power delivery is normally very low. Heat dissipation isn’t as bad as the textbooks would have you believe. On the LSX, fitting a class-AB amp even for the tweeter was not thermally possible, hence our use of class-D for both LF and HF.

When we began work on the LS50W a few years ago, we weren’t convinced that we could get good enough quality for HF from class-D. There are great strides being made in class-D amplifiers. I’m keen to listen to some of the new amps that Bruno Putzeys has been designing. I’ve listened to his Ncore amplifiers, and they’re exceptional. There’s also a new technology that he’s developed.

We’re looking at speakers with more power than the LS50W, and we’ll have to use class-D to achieve that in any kind of sensible product.

GB: So you’re working on other active speakers?

JO-B: We have a few things in skunkworks. The LS50W project has been very instructive. You take a great passive speaker and keep the acoustics the same. Straightaway, you can see what active gives you. But then you ask, does an active speaker need to behave like a passive speaker? We’re used to certain recipes: a box of a certain size, with drivers of a certain size. Another part of this recipe is power, so we’re looking at higher-power LFs in some projects we’re working on behind the scenes.

With active speakers, you can start to break some of the traditional rules. You can trade off efficiency for bass extension. We’ve provided some of this capability with the switchable bass-extension mode on the LS50W and LSX. You can do some of this with analog electronics. But with DSP, you can be much braver. If you’re about to break something, we can step in. That means we can change someone’s optimum system for a given room.

People listen at high levels when they’re shopping for new speakers, or when they’re having a party. But most listening happens at relatively low levels. So if we’re designing a system so that you can’t damage the drivers at maximum levels no one uses, that’s wasteful in a way. It’s possible to get much bigger performance without a bigger box. That’s one of the key benefits active can offer and traditional hi-fi can’t.

Maybe that will get the attention of some traditional audiophiles. I’m quite happy to design passive speakers for the rest of my career, but I’d like to design more active models. We’ll see what happens.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse