Recently, I reviewed the JBL Link 500, a Wi-Fi speaker that incorporates the Google Assistant platform. To me, being able to question a speaker about the weather for the upcoming weekend, and to get a personalized response based on data Google had previously collected, seemed more a novelty than a great technological leap forward. Still, while the idea of having a speaker in my bedroom with a built-in microphone that relays data to Google’s servers didn’t make me paranoid, I was glad that the Link 500 also has a button for switching that microphone off.

Shortly after the JBL review was posted, news of the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandal erupted, and it has continued to dominate the headlines to this day. If you’ve been busy with other things over the past few months, here’s a brief summary of what went down:

A university researcher created a Facebook app that collected extensive personal data from its users as well as, in an apparent violation of Facebook policy, data from those users’ networks of friends. This extensive cache was then sold to Cambridge Analytica, which used it to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the U.K.’s vote on whether or not to leave the European Union, aka Brexit. Public outrage in both countries over the scandal led to a steep decline in the value of Facebook stock, and to Facebook’s chairman and CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, having to testify before the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives.

I bring up Facebook’s woes in the context of smart speakers because the company’s public-relations meltdown happened shortly before the date it had set to launch its own line of smart speakers. That introduction has now reportedly been delayed, from May to October 2018.

Given the current situation, the delay is understandable: A recent Reuters poll found that only 41% of Americans trust Facebook “to obey laws that protect your personal information.” The same poll calibrated the public’s trust in Yahoo -- a company that, in 2013, suffered a data breach that affected all 3 billion of its user accounts, then failed to disclose the hack until several years later -- as higher than its trust in Facebook, at 47%. With public confidence in Facebook trending below even Yahoo, an October launch for a Facebook-branded smart speaker strikes me as extremely optimistic.

If Facebook does eventually sell a speaker that turns out to be too smart for our own good, it won’t be the first time a consumer-electronics product has violated privacy laws. In early 2017, TV manufacturer Vizio was fined $2.2 million by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission for collecting data about the viewing habits of smart TV owners and selling that information to third-party marketers. The data Vizio amassed from unwitting owners of its TVs extended well beyond tabulating a preference for Seinfeld reruns; it included age, marital status, education level, household size, and household value.

While the Vizio case is the most high profile, there are other examples in the A/V world of major invasions of privacy. In 2005, music label Sony BMG was sued by the state of Texas for secretly installing spyware on the computers of listeners who used their machines’ disc drives to play or rip CDs. Known as the Rootkit scandal, Sony BMG’s DRM scheme run amok affected more than 20 million CDs and, to make things worse, exposed PCs to malware and other viruses. More recently, a Consumer Reports article detailed how Samsung smart TVs and Roku-enabled models from Chinese manufacturer TCL are vulnerable to hackers, and concluded that most smart TVs enable some form of Vizio-style data collection.

Even before the Cambridge Analytica scandal hit, it was a common joke among Facebook users that the company was listening in on their smartphone conversations. Most evidence of such snooping is anecdotal: You’re talking to a friend about an upcoming hiking trip, and shortly thereafter a Patagonia ad appears in your Facebook feed. (On a related note, I recommend this hilarious episode of the technology podcast Reply All, in which the host tries, and miserably fails, to convince callers that Facebook is using more sophisticated ways of mining data than tapping phone calls.) While Facebook denies that it analyzes the content of phone calls in order to target specific users for specific ad clients, it has admitted that its Android app tracks phone-call and text-message use, though that capability can be disabled by the user.

Like it or not, digital assistants, and data collection and analysis, are the future of remote control. New receivers from Denon, Marantz, and Yamaha all support Amazon Alexa skills for voice control and for streaming from services that include Amazon Music and Pandora. Receiver models from Onkyo, Pioneer, and Sony that feature Chromecast Built-in can work with Google Assistant when configured via the Google Home app. As voice activation and control become more sophisticated and mainstream, they’re destined to appear in an even greater range of audio products as listeners ditch clunky iOS/Android apps, which never quite succeeded in becoming suitable replacements for traditional hardware remotes.

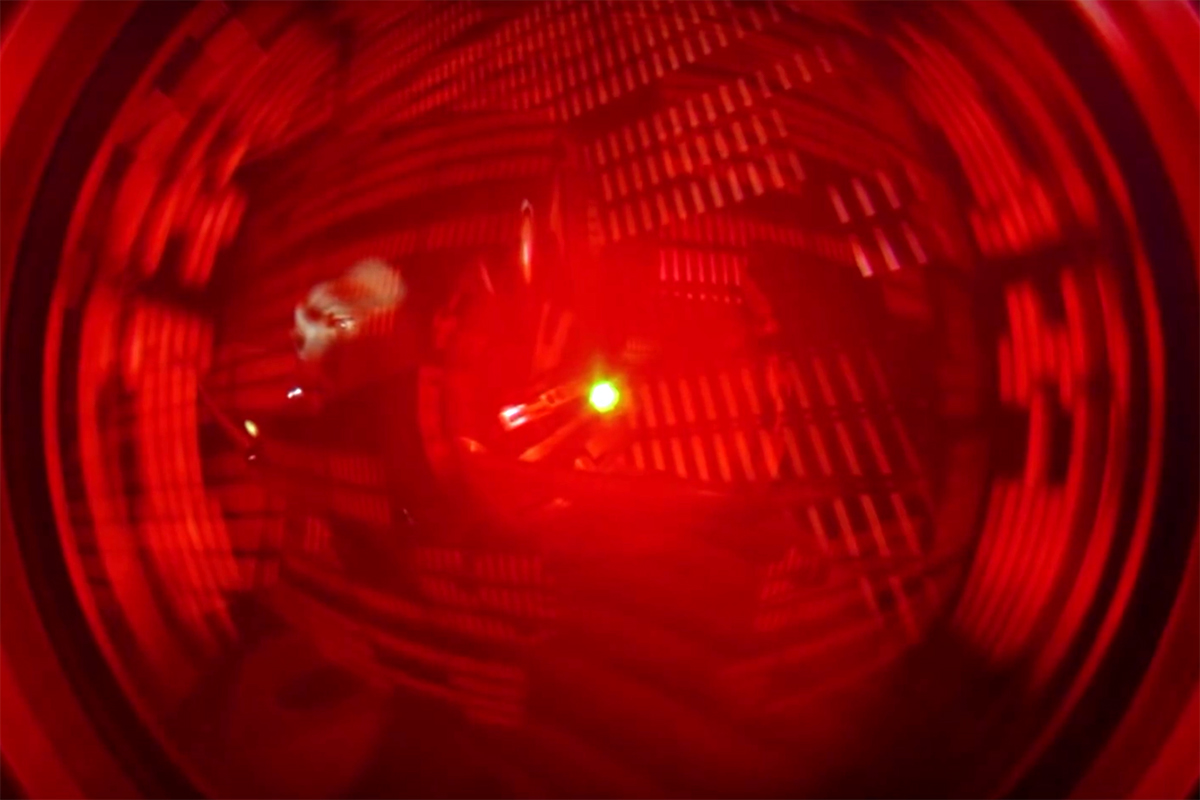

What can music fans expect in this new HAL 9000 world? For one, greater convenience, as their listening activity becomes streamlined and automated by voice commands. However, that convenience will come at a price: the surrender of personal data to cloud-based giants with always-on microphones deployed in your living space. For many people, their selection of a digital assistant -- whether from Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, or Microsoft -- will come down to a matter of trust: Which company is least likely to violate my privacy? When the company in question is Facebook, with its history of irresponsibly selling off data for questionable marketing purposes, inviting its speaker into your home will be like granting entry to a vampire.

. . . Al Griffin