Lately, I’ve noticed that a growing number of products reviewed on Simplifi and other sites on the SoundStage! Network are only available for purchase online. Here are some examples: Denmark’s Buchardt Audio, whose Anniversary 10 active loudspeaker I reviewed on February 1, sells exclusively over the internet. So does Norway’s Arendal Sound, whose 1723 Tower S loudspeaker Philip Beaudette recently reviewed on SoundStage! Hi-Fi. Fluance and Axiom Audio, both based in Canada, sell exclusively online. Thom Moon has enthusiastically reviewed several Fluance products on SoundStage! Access, most recently the RT81+ turntable and Reference XL8F loudspeaker.

There are other brands that focus mainly on online sales but still have a retail presence. SVS has a direct-to-consumer business model, but also sells through retail. Magnolia Audio Video Design Centers, which are owned by Best Buy, carry SVS products in the US. And SVS has independent retailers in many other countries.

On the flip side, many major brands that distribute through retail also sell direct to consumers. Some, such as Bluesound and KEF, make their entire product range available through their own online stores. Others, such as Bowers & Wilkins, Marantz, and NAD, sell a limited selection of their products on their websites, with other models being retail-only.

And of course, most audio retailers now have online storefronts. Some, such as Virginia-based Crutchfield, have huge online operations that dwarf their bricks-and-mortar presence.

For consumers, there are benefits and drawbacks to all these business models. Let’s have a look at the trade-offs, which are more complicated than you might think at first.

The cost of doing business

Online-only brands tout price as a major advantage over retail-based products. On the surface, this seems to make sense.

Retail profit margins on audio components like speakers and amplifiers are typically around 30%. That’s a rough average, though. On mass-market entry-level components, gross margins may be closer to 20%, though bulk buying and other incentives can bump this up by several points. On slower-moving high-end components, gross margins can be 40% or higher.

Typically, though, if a dealer is selling an amplifier for $1000, the wholesale price was somewhere around $700. That doesn’t mean the dealer is pocketing $300. A big chunk of the gross profit has to cover overhead—rent, utilities, payroll, marketing, fixtures, etc.

Then there are the costs of getting the products into stores. Brands that distribute through retail have to maintain direct sales forces and invest in dealer training. They may also have to underwrite some of the retailer’s marketing expenses through co-advertising programs. Especially for small independent stores, there’s often an additional tier of distribution between the manufacturer (or manufacturer’s overseas subsidiary) and the retailer.

Direct-only brands say they can sell more cheaply because they don’t have those costs. “We have eliminated expensive marketing, distributors, agents and Hi-Fi dealers,” Buchardt Audio states on its website. “By selling directly to the end user, we eliminate a huge part of the cost in comparison to our competitors.”

It’s not quite that simple. Direct sellers are acting as retailers, and face costs associated with retailing. They have to ship product to consumers one at a time, rather than shipping a whole bunch of stuff at once to a dealer or distributor. They’re dealing with end users individually, rather than having a dealer network handle those relationships. That may involve operating a call center and online chat services, with associated costs for staff, office space, and equipment. Direct sellers also have to pay for marketing.

Even so, I think it’s safe to say that online-only brands enjoy a price advantage over brands that sell through bricks-and-mortar stores. I got some insight on this issue last year when I learned that a manufacturer had complained about a SoundStage! review comparing their product to a model from a manufacturer that sells direct. That unfairly skewed the comparison in favor of the direct seller, the manufacturer maintained.

The price advantage applies only to brands that sell exclusively (or almost exclusively) direct. Brands like Bluesound and KEF that sell through both direct and retail channels will set prices the same for each. Manufacturers with a hybrid business model can’t be seen to be undercutting their dealer network.

In the flesh

Another advantage that direct sellers tout is the ability to try components in your own home. Some online merchants offer a free trial period that can range from 30 to 60 days; others apply a charge for returns. Buchardt Audio, for example, has a 45-day trial period but charges €100 for returns. Axiom Audio has a 30-day trial period, but customers have to cover shipping costs for returned goods.

On the surface, in-home trials are very appealing because a component may not perform the same way in your home as it does in a retail showroom. That said, you can almost always make an informed judgment about how a component will sound at home by listening to it in a store.

And there are many things you can do in a retail store that you can’t do during an in-home trial, like comparing products from different manufacturers. Want to hear how Paradigm’s Persona 7F floorstanding speakers compare with Bowers & Wilkins’s 802 D4s? You can do that at Trutone Electronics in Mississauga, Ontario, which is where I took the photos for this article.

A capable retailer can also help you with system matching. Is an Anthem STR preamp and STR power amp a good match for the big Paradigm Personas? How about the Rotel Michi X5 Series 2 integrated? Does a 50Wpc Rotel A11 Tribute integrated amp have enough juice to drive a pair of Bowers & Wilkins 603 S3 floorstanders or Monitor Audio Silver 100 7G minimonitors? A demonstration conducted by an informed salesperson can make these decisions easier.

You can also see and touch products for yourself when shopping in-store. How does the volume control on the Michi amp feel? How do a pair of Focal Sopra N°2 speakers finished in orange look up close? You can get an idea of these things from online reviews. But there’s no replacement for experiencing them in the flesh. Of course, no retailer can carry everything. If I want to see how the Sopra N°2 looks in smoked oak, I may have to look online. If I want to compare the Sopras or Personas with a pair of KEF Blade Two Metas, I’ll have to go elsewhere. Or more likely, I’ll have to listen to the Personas at one shop and the Blades at another.

Most importantly, in a retail setting you’re dealing with a flesh-and-blood human being, not an anonymous staffer in a call center. In my experience, most audio salespeople are in the business because they love audio. Many have decades of experience with dozens of different brands. The ability to evaluate a selection of curated components from different brands in a comfortable environment under the guidance of an experienced salesperson has value.

They want to sell—and upsell

Note the job description, though: salesperson. Retail personnel aren’t consultants. Almost always, commission is a major part of their compensation packages. That doesn’t mean they’ll start turning the screws after you’ve been in the store for 15 minutes. Thankfully, high-pressure tactics are much rarer now than when I worked in retail a half century ago—mainly because they don’t work. But salespeople need to sell. For sensitive types, that’s one downside of buying retail. You’re interacting with someone who, deep down, wants to get the deal done. Online shopping doesn’t involve that stress.

While most salespeople today take a more consultative approach to their work, that doesn’t mean they’re unbiased. Naturally, they want to steer customers to products their store carries. More often than not, that bias is born out of a genuine belief in the value of their products. But there are sometimes hidden agendas, such as extra bonuses for selling a specific brand or model, paid either by the retail employer or product supplier.

Salespeople don’t just want to sell; they want to upsell. At some point during the sale of an amplifier, turntable, or pair of speakers, a salesperson will almost inevitably introduce the topic of cables and other accessories. Compared to hardware components like DACs and amplifiers, cables and accessories have much higher profit margins—typically 50% or greater. Salespeople are incentivized to push these products, and they can be very convincing. This is another form of pressure you won’t face online. There may be a box in the checkout page that you can click to add an accessory, but you won’t have someone pushing you to click on it.

Actually, I don’t have a problem with add-on sales. For one thing, these products are an important part of any store’s profit picture and any salesperson’s compensation. They can make the difference between eking out a living and enjoying a decent livelihood. Of equal importance, sincere and well-informed salespeople can direct you to accessories that will enhance your system’s performance. Just because they’re encouraging you to add an accessory, and earning some extra money if you do, doesn’t mean that the accessory lacks value.

For many years, I was skeptical about premium cables, and I still cock an eyebrow at the more outrageous claims of cable manufacturers. But for an article I wrote in 2015 for a Canadian technology magazine, I removed the generic cables I was using at the time and substituted premium cables from two different manufacturers (AudioQuest and Wireworld), lived with them for a couple of weeks, and then went back to my original cables. I preferred the sound of my system with the premium cables and ended up shelling out several hundred dollars for a fresh loom.

Crossing the line

But I draw a very hard line around another common form of upselling—service plans and extended warranties. Far too many retailers do this, not just in the real world, but online too. I think these things are a swindle, or to put it more politely, an outrageously expensive form of insurance.

Here are some things I learned while researching an article on this subject for a retail trade magazine about ten years ago. Typically, the store selling a service plan receives a 50% commission. Remember, that’s not profit earned on a piece of inventory, it’s basically a kickback. Retail salespeople who don’t push these plans hard enough are sometimes forced to stay after-hours for role-playing seminars conducted by the purveyors of these plans.

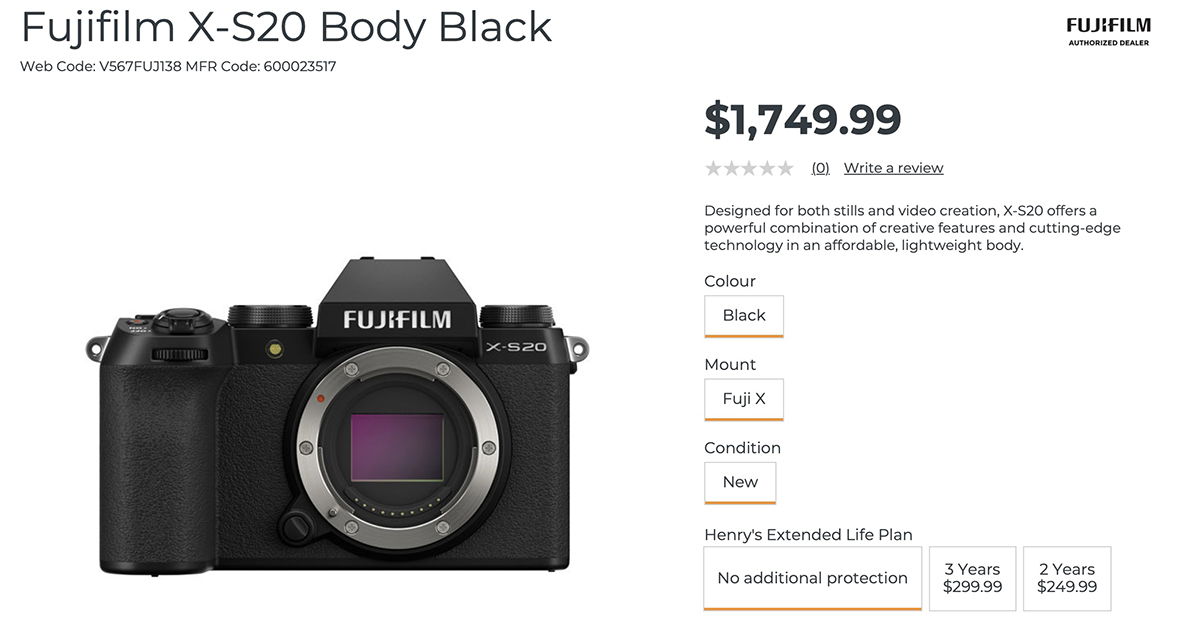

If you think my characterization of these plans as a swindle is too harsh, consider this example. Last fall, I bought a new camera, a Fujifilm X-S20, which at that time was in short supply. I phoned the nearest branch of a big Canadian photo chain to see if the camera was in stock and to get a price. I was told that it was available and the price was $1749 (CDN) “plus $299 for a service plan.” I said that I wasn’t interested in the service plan, but would like to come down and pick up the camera. The salesman then informed me that the camera would have to be ordered.

Let’s do some math. The $299 price for that three-year service plan is 17% of the retail price of the camera. If the camera were to break during that term, the underwriter of the plan would have the camera fixed or get me a new one, as long as the damage was not my fault. If it was my fault, I’d get a 20% discount on the repair bill. What are the chances of such a failure happening outside of the manufacturer’s warranty period? 100:1? 500:1? 1000:1? But the underwriter of this plan is basically offering a bet with odds set at 6:1. Only a sucker would take such a bet.

This example isn’t an outlier. The math will work out much the same for any service plan for any consumer product. If a retailer asks you to add a service plan to your purchase, my advice is always to say no: a very emphatic no.

This is obviously a bugaboo of mine. I’ve ranted about it because it’s something that too often spoils what would otherwise be a pleasant retail transaction. It happens in the online world too, but there it’s easier to just not click the box. There’s no salesperson trying to persuade you that you’re taking an awful risk—and make the item unavailable if you don’t bite.

Face-to-face

I think there’s a place for both online distribution and for bricks-and-mortar shopping in our hobby. Online distribution is obviously a boon for people who don’t live in big cities, because it greatly expands the range of brands and products available to them. And it’s good that there are online-only (or online-mainly) brands offering better performance for less money.

My first professional involvement in audio was through retail. I worked as a salesperson for a Toronto audio chain while attending university in the 1970s, and I still have a soft spot for the retail experience. In audio, unlike many industries, numerous retailers continue to thrive, and I’m glad of that. In our disintermediated world, it’s good that some business is still conducted face-to-face.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse