For his February 1 “SoundStage! UK” column on SoundStage! Hi-Fi, Ken Kessler wrote an entertaining (but slightly unhinged) rant, “I Hate Streaming.” Characteristically, Ken spiced up his piece with colorful prose. “As for streaming, I can’t even be bothered to dignify it by hating it,” he proclaimed. “Rather, I prefer to disrespect it with the ultimate insult: I couldn’t care less about it. . . . Indeed, when suffering insomnia, I think of streaming. Then, when I invariably wake up at 3 a.m., being of pensioner age, streaming is exactly what I do. In the loo.”

Chuckles aside, I want to focus on Ken’s principal points: that streaming is sonically flawed and morally wrong. “Every time the audio industry prioritizes convenience or cost savings, it sacrifices sonic merit,” he insisted. A more serious issue is “the shoddy treatment of musicians by the streaming services.”

Sound quality vs. convenience

Let’s look at the sound issue first. “Imagine that there is a square diagram of ‘Formats vs. Sound Quality’ cut into quadrants,” Ken wrote. “In the upper right corner will be 1″ and 2″ analogue master tape. . . . In the diagonally opposite corner will be MP3 or the current holder for worst digital product. Roughly in the middle might be cassettes, with the LP in between cassettes and open-reel. CD will sit somewhere in the lower left quadrant, etc.”

I’ve heard open-reel tape on only a few occasions, at audio shows, but I don’t doubt for a second that it belongs in the upper-right corner of Ken’s square. As to the lower-left quadrant—the worst sound—I’ll grant his assertion that that area should be filled by “MP3 or the current holder for worst digital product,” but with reservations. Depending on bitrate, the sound of compressed formats like MP3 can range from horrible to OK.

But there’s some sleight-of-mind going on here: conflating streaming with lossy compression. The two are not coextensive. True, the leading streaming services use lossy compression: Spotify uses Ogg Vorbis, Apple uses AAC, Amazon Music uses MP3. But there are better-sounding options, as Ken surely knows.

While Amazon Music uses MP3 compression for its standard tier, listeners who want something better can opt for Amazon Music HD, which offers lossless CD-resolution and high-resolution streaming. Tidal’s HiFi tier offers lossless CD-rez streaming, as well as MQA-encoded Masters hi-rez albums (please, everyone, let’s not get into an MQA flame war here). Qobuz doesn’t use lossy compression at all—everything is CD-rez or better. Deezer has a lossless tier. For classical-music listeners, Idagio and Primephonic both operate streaming services with lossless CD-rez tiers—Primephonic also has hi-rez content. Later this year, Spotify will add a hi-fi tier with lossless CD-resolution music.

Wherever these premium services belong in Ken’s diagram, it isn’t in the lower-left quadrant. They’re somewhere in the middle—and, in my experience, closer to the top than the bottom. Exactly where will depend on what you’re listening to and what you’re listening through.

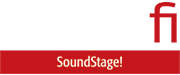

There’s no question that the Blue Note LP of Kandace Springs’s The Women Who Raised Me, played on the Pro-Ject RPM 10 Carbon turntable ($4000) Jason Thorpe reviewed for SoundStage! Ultra in December 2017, would sound different from Qobuz’s 24-bit/96kHz FLAC stream of the same album played through the Lumin T2 network music player ($4500) I reviewed for Simplifi in October 2019. Would the vinyl rig sound better? That would be in the ear of the beholder; what I think is indisputable is that both would sound glorious.

You can repeat the same mental experiment with differently priced setups. Played through a Bluesound Node 2i ($549), Tidal’s 24/96 MQA stream of The Women Who Raised Me would sound different from the LP spun on the Pro-Ject Debut Carbon Evo ’table ($499) Thom Moon reviewed on SoundStage! Access in December 2020. Would it sound inferior? I don’t think so, though I’m sure different listeners would have different preferences—and I’m sure the album would sound great on both setups.

If I were filling in Ken’s quadrant, LPs and hi-rez streaming would overlap. I don’t think that streaming, at its best, takes a back seat to vinyl at all.

What about convenience? That cuts both ways. Initial setup of a network streamer can be almost as fiddly as setting up a turntable—in different ways, of course. For daily use, I find it far more convenient to cue up music from an app on my iPad than to scan shelves for the disc I want to hear. But I know many people who find it much easier to spin a CD or LP than fiddle with apps.

Where Ken’s piece goes off the rails is his dismissal of streaming as a distribution format for distracted millennials. “I am not of the age group that sits in front of a phone or laptop to watch a film while wearing nasty earbuds, eating pizza, and drinking Red Bull,” he proclaims. “I am not seduced by whatever is this year’s gaming hit. I do not listen to my fave tunes while riding a Peloton.”

There’s some fun writing here, but it misses the point. The fact is that streaming is a legitimate choice for music lovers who are serious about sound—and for some of those people, it’s the best choice.

Accompanying Ken’s article are photographs of his music collection, hi-fi system, and listening room. Such a space is an unimaginable luxury for many music-lovers, including yours truly, who live in small city homes. As I’ve written elsewhere, hi-rez streaming makes it possible for my better half and me to enjoy great sound in our main-floor living room—the only room in our house where it’s possible to set up a music system.

Conscience vs. cost

What about the moral dimension? Calling streaming “a form of cyber robbery,” Ken quoted, in the following sentence, an article in the British magazine Private Eye that reported on an investigation of music streaming by the UK government’s Department of Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport: “Streaming generated £1 billion ($1.35 billion) in the UK, ‘of which as little as 13 percent found its way to those making the music.’” Ken didn’t specify the period during which streaming generated that billion quid, but no matter.

Those impressive top-line numbers notwithstanding, streaming services are still not turning a profit. For the quarter ending December 31, 2020, Spotify had a worldwide operating loss of €69 million. True, there could well be some creative accounting going on here—Spotify posted a gross profit of €575 million for the same period. The company says increased social charges, such as employee benefits, led to the operating loss. It sure looks like the company is getting set to rake in big bucks (euros, actually).

Ken also quotes that Private Eye article’s citing of “evidence from ‘musicians about how badly they are ripped off by the likes of Spotify’ and other services.” The first is a composer who “created a loop that played one of his works over 1100 times on Spotify as an experiment; it earned him 87p ($1.18).” Let’s unpack those numbers a little, and see how that $1.18 that composer got from streaming might have compared with earnings from a CD or download sale.

A one-track download on Apple’s iTunes store costs 99¢, the same as a 45rpm single way back when. People don’t play downloads or records just once (unless they’re really bad). So how many times might someone play a download or a favorite track from a CD or LP? To keep the math simple, let’s assume 100 times.

Given my assumption of 100 plays per download, 11 downloads of that song would generate the same number of plays as that composer’s experimental Spotify loop. Those downloads would generate $10.89 in revenue, to be shared by the download store (e.g., iTunes), record label, composer, and musicians. According to a recent article on Investing Answers, Apple keeps 37% of each download sale; 53.5% goes to the label, and 9.4% to the artist. So from our hypothetical 11 downloads, $1.02 would be divided among the artists—or go to a single artist, if only one was involved.

Maybe a typical download is played only 50 times, or only 20. In those cases, it would respectively take 22 or 55 downloads to generate 1100 playbacks, which would mean $21.78 or $49.50 to be divvied up. The big picture remains the same: Unless my assumptions are wildly mistaken, for musicians, streaming revenues aren’t a whole lot different from download revenues.

The payouts are better with CDs, but not meaningfully so. According to that same article in Investing Answers, “the average high-end royalty deal with a record company will pay musicians $1 for every $10 retail album sale; . . . a low-end royalty deal only pays 30 cents per album sale.” Let’s work out some numbers for a $15 CD with ten songs. The value of each song is $1.50. Assuming 100 plays over the life of the CD, the payout to artists for 1100 plays of that song will be $4.95 under a high-end royalty deal, $1.65 under a low-end deal.

The second example was a violinist who “showed how five million streams of one of her works on Spotify over six months paid her £12 ($16.32).” That sounds pretty egregious. The musician is the acclaimed British violinist Tasmin Little, whose most-streamed work on Spotify is Vaughan Williams’s The Lark Ascending, with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Andrew Davis. The artist payout is likely being spread among many performers—after the label has taken its cut.

An article on musically.com expressed puzzlement at the low payout Little received: “Tasmin Little’s 5-6m streams should have generated label payouts of between $17.4k and $20.9k. How that translates to just over sixteen dollars for the artist is . . . well, it’s certainly a spark for even more debate.”

I’ve learned to be suspicious about statistics cited in support of marketing and regulatory initiatives. All too often, they’re presented without context, or gussied up to make a case for the sponsoring group. It’s worth remembering the famous saying, erroneously attributed to Benjamin Disraeli, Mark Twain, and others: “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.”

The more important takeaway here is that streaming has changed little about musicians’ livelihoods. Ken cited Mick Jagger’s response to a magazine writer who asked why the Rolling Stones continued to tour: “the era of making money from music sales was over and . . . concert ticket sales and merchandise were the only earners.”

Here’s the thing: For almost all of history, musicians have earned their money through live performances. Like those of other creative artists, the livelihoods of most musicians have always been precarious.

The “era of making money from music sales” was a historical blip—less than a century. Even during that period, the proportion of musicians who made a living income from record sales probably wasn’t very different from the proportion who today make a living income from streaming. In the recording industry’s boom years, from the 1960s through the 1990s, when people were buying LPs and then CDs by the boatload, the vast majority of working musicians still had to play live gigs to make a living.

A few years ago, in an interview for the Canadian magazine Wifi Hifi, I discussed the impact of streaming on musicians’ livelihoods with Toronto writer David Sax, author of The Revenge of Analog. “The story of the music business screwing artists over is as old as time,” Sax stated. “The reality is, if you are looking to get music out to as many people as possible, the simplest way is digital and streaming.”

The last part of Sax’s observation is important, because it raises another important thing about streaming. Working musicians need to earn money, but most want something else as well. Like all creative artists, musicians crave an audience for their work, and streaming helps them develop and expand that audience.

This cuts in both directions. Streaming is a risk-free way to explore new music and discover new musicians. In the past, if I read about an interesting new band, I’d have hesitated before buying one of their albums. But I don’t hesitate about streaming interesting music by a performer who sounds promising.

Musicians and labels don’t have to sign streaming contracts. The British classical label Hyperion licenses none of its content to streaming services. If you want a Hyperion recording, you have to buy a disc or a download. I’ve bought several.

Just because you’re streaming doesn’t mean you have to stop buying music. I still do. I’ve bought downloads of music I love just to have it in my collection, and I’ve bought music after attending a concert, and want the band’s album in my collection.

Spotify is the largest streaming service, and one of the stingiest. There are other options for music lovers who’d like to see artists compensated more fairly. According to an article on Digital Music News, Apple Music’s per-track payout to rights-holders is almost double that of Spotify, and Tidal’s more than triple.

Idagio and Primephonic have per-minute payout structures that are much fairer to classical performers like Tasmin Little than the major services’ per-track payouts. Little’s performance of The Lark Ascending is 15 minutes and 35 seconds long—about four times as long as the average pop song.

The bottom line: music lovers who are concerned about fairness to artists can tailor their music-consumption habits to reflect that concern—without foregoing the benefits of streaming.

In his article, Ken criticized streaming on sonic and moral grounds. “If you’re heartless and couldn’t give a toss about the musicians, so be it,” he proclaimed. “If you revel in convenience and don’t mind sacrificing sonic merit, go for it.” He’s wrong on both counts.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse