In my last three columns, I wrote about how streaming is changing the ways people discover and experience music. In my January feature, “The State of Streaming,” I looked at streaming services that deliver lossless CD-resolution and high-resolution music. In “The Name Game,” published February 1, I wrote about how streaming has given rise to whole new classes of audio components, and set out to establish some definitions. And in my March feature, “Rules of the Game,” I discussed the software protocols that enable these new components to talk to one another, and compared their benefits and drawbacks.

My focus in that last feature was on audio, but this month it’s video -- specifically, how music lovers can stream video from their laptops, tablets, and smartphones to a TV and audio system. Still, my interest remains musical content -- mainly concerts, but also music videos -- as opposed to movies and TV shows from such services as Netflix and Hulu.

What’s out there

I’m sure everyone reading this article knows there’s a wealth of great musical content on YouTube, but I don’t know if they appreciate the range and quality of that content. One reason is the amount of dross you have to skim off to find the gold. Search for content by a favorite artist and, alongside official music videos and extended concert footage, you’re likely to see a bunch of ripped albums with scrolling lyrics that fans have uploaded.

One obvious clue of worthwhile content is the viewer count. If a music video has been watched thousands of times, chances are it’s pretty interesting, and has the imprimatur of the artist. And many musicians, on their own websites and social-media feeds, post links to YouTube videos of their music so you don’t have to sort through the dreck to find the good stuff.

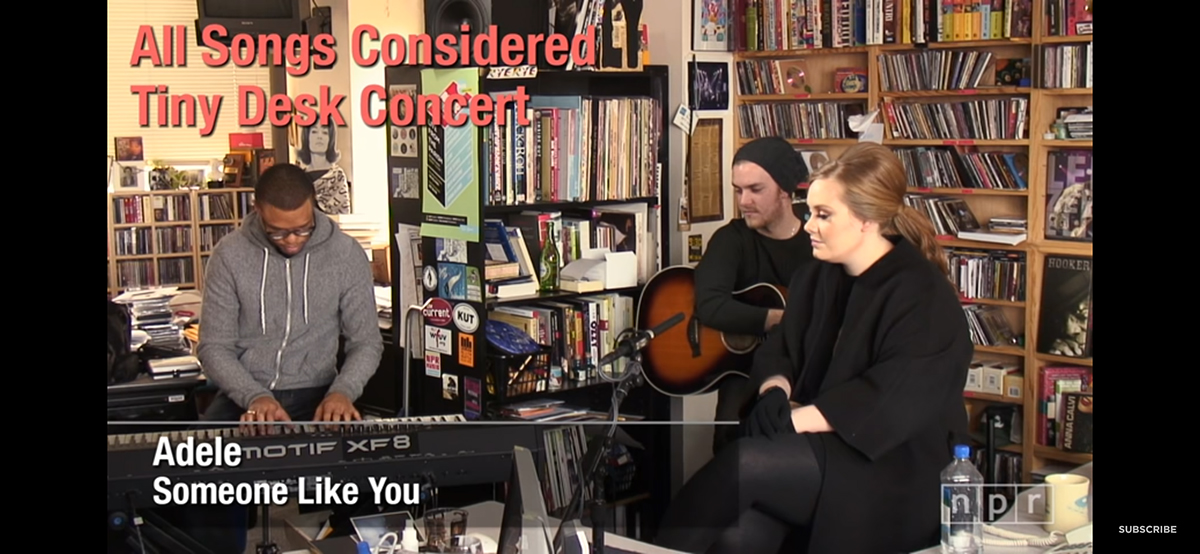

One of my favorite YouTube channels is National Public Radio’s Tiny Desk Concerts, which archives their broadcasts of that title. Recorded at NPR’s studios in Washington, DC, the concerts feature artists as varied as Adele, Rosanne Cash, Coldplay, Rhiannon Giddens, Lizzo, Yo-Yo Ma, and Wu-Tang Clan. Collectively, the 800 Tiny Desk Concerts have been viewed two billion times, per Wikipedia. Each performance lasts 15 to 25 minutes -- perfect for a quick musical snack.

If you want a full meal, YouTube also hosts hour-long concerts from the Newport, Monterey, and Montreal jazz festivals, and full episodes of PBS’s Austin City Limits -- and those are just the tip of the iceberg. I’ve whiled away many pleasant hours watching concerts like these.

And, of course, there are plenty of music videos. Two recent videos that stand out for me are “Happens to the Heart,” from Leonard Cohen’s posthumous album Thanks for the Dance; and “Me and the Devil,” from Gil Scott-Heron’s final album, I’m New Here, each in its way deeply affecting.

Beyond YouTube

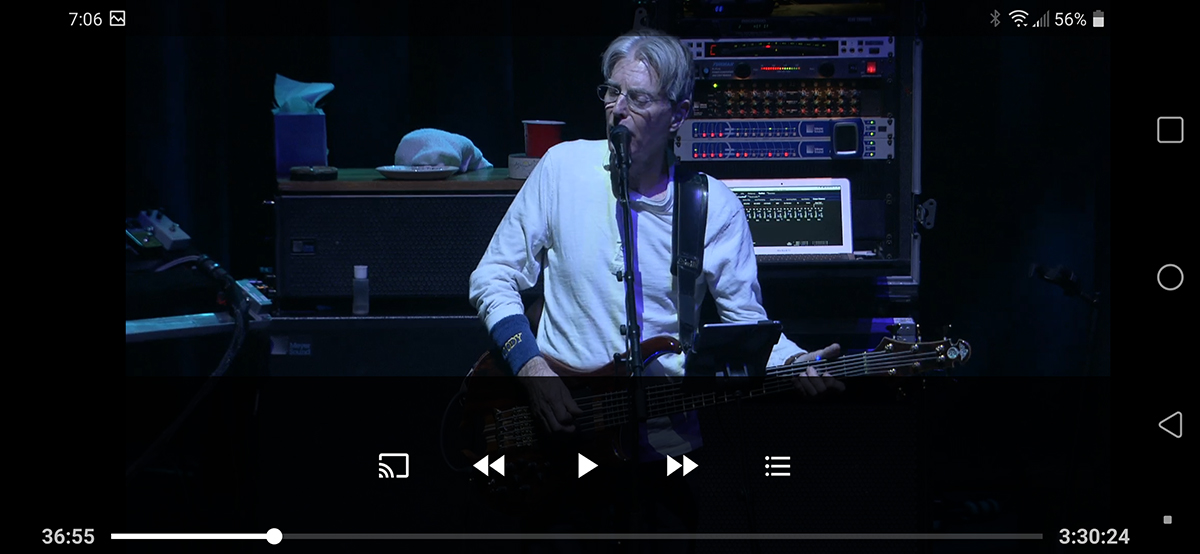

Tidal subscribers can find music videos, playlists, and concerts on the home screen of the Tidal app. The selection is heavily weighted toward hip-hop and related genres. Nugs.net is a service specializing in live rock concerts; while most of its content is audio only, it also has a good selection of music videos and regular live webcasts.

If your taste runs to classical, some very interesting subscription services specialize in symphonic music and opera. These include the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra’s Digital Concert Hall (€14.90/month), and the Metropolitan Opera Company’s Met Opera on Demand ($14.99/month). Both services have performances from the current seasons, as well as archival performances. The BPO’s Digital Concert Hall also offers artist profiles and interviews. The production values of both services are superb -- feature-movie quality, or close to it. During the COVID-19 crisis, Digital Concert Hall has been offering free vouchers giving full access to the service for 30 days, while Met Opera on Demand has been making a full performance from its archives available for free every day -- the schedule is posted at the beginning of each week.

As crises so often do, the COVID-19 situation has inspired bursts of creativity and generosity. Scores -- maybe hundreds -- of musicians, including Beyoncé, Garth Brooks, Melissa Etheridge, John Legend, and Metallica, have been posting free video performances on their Facebook pages and Instagram feeds. Throughout the crisis, the tech site CNET has posted daily updates outlining the free performances available that day.

I’ve been catching the performances of jazz pianist Fred Hersch, who, each day at 1pm EDT, sets up a mobile phone next to his piano and live-streams a short performance. These “Tune of the Day” videos then remain on his Facebook page for later viewing. Performances like these are personal and intimate, and best appreciated via a smartphone and headphones.

But big events -- YouTube concerts from the major jazz festivals, Austin City Limits, Nugs.net rock concerts, classical performances from Digital Concert Hall and Met Opera on Demand -- cry out for a big-screen TV and a top-notch sound system.

Showtime

Getting this content from your smart device to your entertainment system is pretty simple. As I noted in my March feature on streaming protocols, Apple AirPlay and Google Chromecast both support video and photo streaming, as well as audio. You can cue up a concert on your smartphone, tablet, or laptop, then tap an icon and let the show begin.

AirPlay can stream video from any video app on an iPhone, iPad, or Macintosh computer to an Apple TV media adapter. The Apple TV HD ($149) and Apple TV 4K ($179 for 32GB version) have Wi-Fi and Ethernet networking, and HDMI outputs. The HD version has maximum video resolution of 1080p, while the 4K version supports 4K video with HDR imagery, as well as Dolby Atmos immersive audio. A 64GB version of the Apple TV 4K is available for $199, but you need the extra storage only if you plan to download extra apps and games.

Apple TV lets you buy and rent movies and TV shows from Apple’s iTunes store, and stream video from services like Netflix and Amazon Prime Video. But here I focus on using an Apple TV as an endpoint for video from mobile devices and laptops.

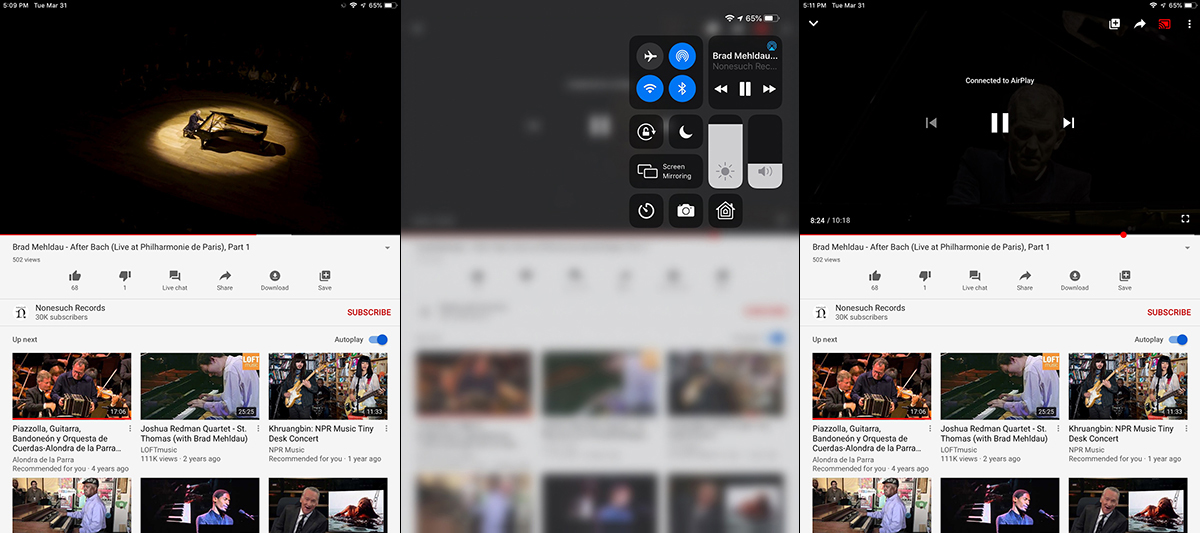

It’s pretty simple. Get the unit connected to your home network, connect its HDMI output to your TV or A/V receiver, then cue up the content you want on an iPhone, iPad, or Mac. If you’re using a device running iOS 12, pull down from the upper-right corner of the screen to see the Control Center. (In iOS 11, you swipe up from the bottom center.) The upper-right tile in the Control Center will show the AirPlay icon -- tap it to show the AirPlay devices on your network. Choose your Apple TV adapter, and playback will begin and shift to your Apple TV. If you want to stream from a Mac to an Apple TV adapter, click on the AirPlay icon on the right side of the menu bar and select Apple TV. The first time you stream from a device to an Apple TV, you’ll have to enter a four-digit code shown on the TV to confirm pairing -- a onetime process.

As I noted in my feature on streaming protocols, with AirPlay, the same device acts as controller and streamer. If you’re streaming a YouTube video from your iPhone to an Apple TV adapter, the signal flows from your network router to your iPhone to the Apple TV adapter. If you close the app on your iPhone, the show stops.

Google offers two different Chromecast dongles, both with HDMI outputs that connect to your TV or AVR. The standard Chromecast ($35) has a maximum video resolution of 1080p, while the Chromecast Ultra ($69.99) supports 4K and HDR. With a Chromecast adapter, you can stream audio and video from Cast-enabled apps on an iOS or Android device, or from Google’s Chrome web browser on a Windows PC or Mac.

With Cast-enabled apps, signals stream from the internet to your network router to your Chromecast adapter without going through your smartphone or whatever other control device you’re using -- that device acts only as a controller. If you close the app or power off your device, the show goes on.

There are thousands of Cast-enabled apps, but some services aren’t supported by Chromecast. For example, the BPO’s Digital Concert Hall, Nugs.net, and Tidal apps are all Cast-enabled, but Met Opera on Demand is not. If you want to send video to a Chromecast adapter from a service whose app is not Cast-enabled, you can do so by accessing the service from the Chrome browser on a PC or Mac, then selecting the Cast option in the View menu. If you’re Casting from the Chrome browser, the show will stop if you close the browser.

To send video from a Cast-enabled app to a Chromecast adapter, cue up the content you want, then tap the Casting icon in the Now Playing window, and select the Chromecast adapter from the list of available devices. Playback will shift from your device to the Chromecast adapter and your TV.

The current versions of Apple TVs and Chromecasts have only HDMI outputs -- there are no separate audio outputs. That might pose a challenge to those who want to play audio through a separate sound system -- as I think most SoundStage! readers will. It’s not a problem if your TV has audio output jacks. I have an Apple TV and Chromecast connected to the One Connect set-top box that came with my 55” Samsung Frame TV. The One Connect has a TosLink S/PDIF output, so I can route audio to any component with a TosLink input. Nor is it a problem if the media adapter is connected to an audio component with HDMI inputs and outputs, such as an AVR, and from there to the TV.

But if you’re connecting the adapter to a TV that has HDMI inputs but no audio output jacks, you’ll need an HDMI audio extractor. As the name implies, these little adapters pull audio from the HDMI signal and output it through TosLink and/or stereo analog jacks. They’re readily available from Amazon and other merchants at very modest prices.

Why use a device?

While most TVs in use today have built-in networking smart features such as YouTube apps, many old sets still in use lack them. And in older TVs with smart features, the software is often awkward to navigate and slow to respond. But even modern TVs with tightly integrated, responsive software for services such as YouTube present lots of reasons for using a smart device and media adapter.

While YouTube support is practically universal in modern TVs, that’s not the case for specialized services, such as Digital Concert Hall and Nugs.net. If you subscribe to one of those services, chances are you’ll have to access it from a computer or smart device.

With most TVs’ YouTube apps, you specify search terms by using the TV’s remote to enter letters, one at a time, on an onscreen keyboard. It’s slow and awkward. With a computer or smart device, it’s far easier to browse content and enter search terms.

Granted, some TVs have speech-recognition features that can make searching easier. With the YouTube app on my Frame TV, I can highlight the microphone icon in the search screen, press the mike button on my remote, and tell the app what I’m looking for. Almost always, it will generate a list of videos that includes the content I want.

Speech recognition has been broadly available on TVs for only a few years -- I suspect that most TVs in use today still lack the feature -- but it’s almost universal on Android and iOS devices. With my iPhone SE, I can say, “Hey Siri, find me some Punch Brothers videos,” and the phone will display several videos in the YouTube app. The same thing happens when I pick up my LG G7 ThinQ smartphone and say, “OK Google, find me some Punch Brothers videos.”

An added dimension

Most of the time when I sit down for some music, I just want to listen. But I also really enjoy having the option of watching the musicians perform -- it deepens my appreciation of the physicality of making music, and gives me new insights into the music I love and the musicians who perform it. The combination of a smart device and a media adapter like a Chromecast or Apple TV makes it very easy to have those experiences.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse