In early May, a curious factoid popped up in my news feed. According to a 2023 study by Los Angeles–based Luminate, a sales analysis company that specializes in entertainment and media, only half of those who bought vinyl records during the previous year actually owned a turntable. Weird!

Or is it? Lots of LPs are purchased as gifts—I bought eight last year. Vinyl records are also bought by a cohort of superfans as collectibles and as a way of supporting artists whose music they love.

Doug Schneider touched on this phenomenon in an April 2023 feature on SoundStage! Hi-Fi: “Vinyl is in fashion these days,” he wrote. “Vinyl is what the cool kids listen to. Vinyl is what some people don’t actually listen to but do hang on their walls.” What if those people decide to play their records? They should proceed with caution, Doug advised. “Many think it would be fun to get into vinyl but aren’t aware of the issues that can spoil that fun.”

A month later, Matt Bonaccio offered a different point of view. “The experience of playing music on vinyl, collecting records, and using hi-fi gear is what I love about this hobby,” he wrote. “Many people find this far more satisfying than streaming music or even playing CDs.”

Superfans who do want to take their LPs off the wall and listen to them need more than a turntable, of course. They also need a phono preamp, an amplifier, and loudspeakers, as well as a suitable listening room. For Gen Z and millennial superfans, who often listen through headphones or powered speakers via Bluetooth, that can be a problem. But there are solutions. Brands like Audio-Technica, Pro-Ject, and Sony offer turntables with built-in phono preamps and Bluetooth transmitters. You can pair them with Bluetooth headphones, Bluetooth speakers, a soundbar with Bluetooth connectivity, or an amplifier equipped with a Bluetooth receiver (either built in or added on).

To my knowledge, the most ambitious Bluetooth turntable currently available is Cambridge Audio’s Alva TT V2 ($1999, all prices in USD unless noted otherwise), the subject of this review. The Alva TT V2 is a robustly built direct-drive model that comes with a premounted high-output moving-coil cartridge. It has a built-in phono preamp and a Bluetooth transmitter that supports the premium aptX and aptX HD codecs.

The Alva is obviously overkill for anyone who wants to play vinyl through a simple Bluetooth speaker or soundbar. For someone looking for a serious turntable to use with a serious sound system, however, it could be just the ticket. But why would anyone want to use a Bluetooth ’table with a serious sound system? Here’s why: with some setups, like the one in the living room of my small Toronto home, it is impractical to accommodate a turntable. My KEF LS60 Wireless active speaker system ($6999.99) has line-level analog inputs that I could feed directly from the Alva’s built-in phono stage—if there were space for a turntable in my living room. But there isn’t.

In my home office, on the second floor, I have a small collection of LPs that I spin on a Pro-Ject Debut Carbon Evo turntable ($599 US version, with Sumiko Rainier cartridge; $869 CAD in Canada, with Ortofon 2M Red). I bought the Pro-Ject ’table to be part of my test bed when reviewing a component with a built-in phono stage. But I also use it to play records through the Q Acoustics Q Active 200 speaker system ($1999) that sits atop my desk. Much like Gen-Z and millennial superfans, I’ve bought several albums so that I could have physical artifacts connected to artists whose music I love. Some of these albums are mementos of the music I listened to as a young adult, others are discoveries I’ve made of more recent artists. I also have a bunch of LPs that I inherited from my parents. When I learned of the Alva TT V2, I thought that its Bluetooth connectivity might allow me to play these records through the KEF LS60 Wireless speaker system in my living room as well.

Description

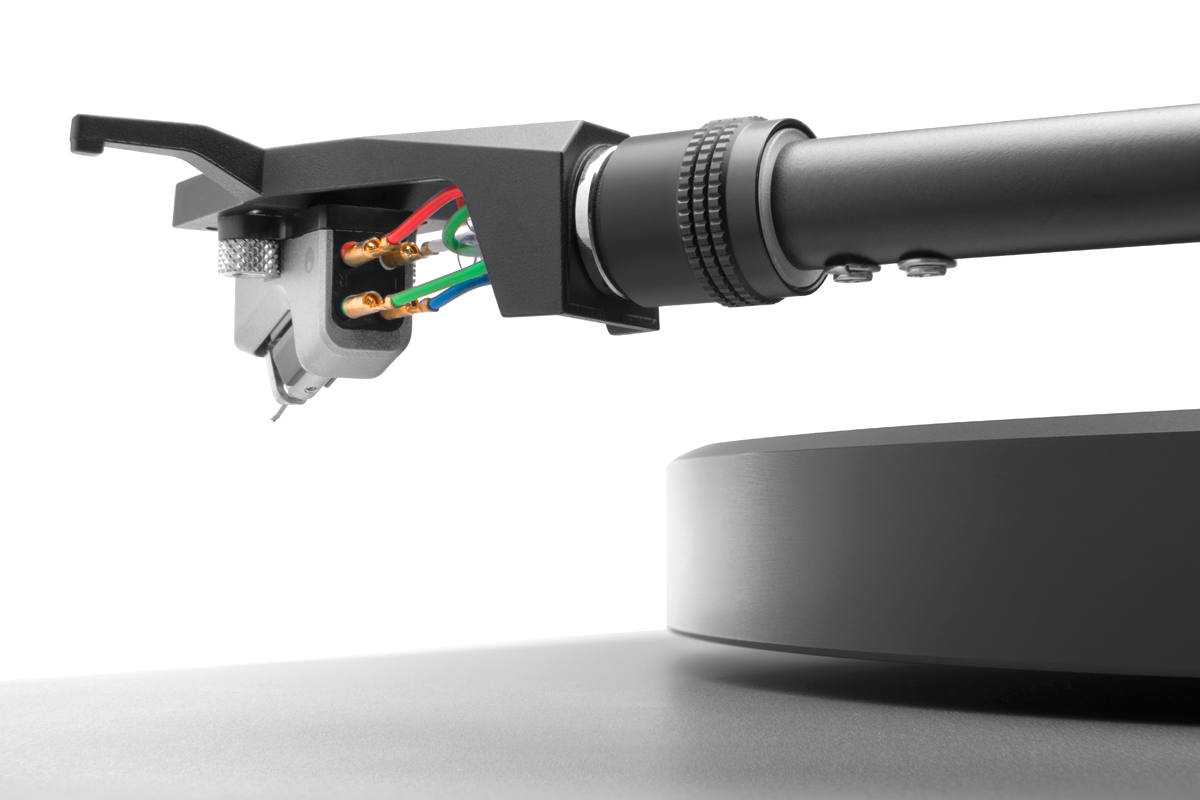

Styled in Cambridge Audio’s distinctive minimalist design language, the Alva TT V2 is an attractive turntable. The aluminum top plate has Cambridge Audio’s signature lunar-gray finish, which contrasts nicely with the matte-black composite-covered MDF plinth and 4.9-pound thermoplastic platter. Records sit directly on the textured top surface of the platter; no mat is supplied. The inner 4.5″ of the platter has the same lunar-gray finish as the top plate.

Measuring 5.5″H × 17.1″W × 14.5″D and weighing 24 pounds, the Alva TT is a substantial piece of kit. The top plate offers three buttons on the left: a silver-colored power button and two smaller ones for selecting the rotational speed (33⅓ or 45 rpm). Cambridge Audio’s logo is embossed on the right.

The straight static-balance aluminum tonearm has a removable headshell. The ’arm and headshell have a satin-black finish, the cueing lever and platform are shiny silver.

Looking at the turntable from the back, you see the two receptacles for the dustcover hinges flanking the plinth on either side. Closer to the center are a grounding pin, a two-position Output Level switch for turning the built-in phono stage on and off (the default setting is off), a pair of RCA output jacks, a Bluetooth indicator LED, a switch for turning Bluetooth on and off, a Bluetooth pairing button, and a three-prong IEC power inlet. The LED blinks rapidly during pairing mode, blinks slowly when searching for the last paired device, glows solid blue when paired to a device, and blinks periodically when paired using the aptX or aptX HD codec.

Included with the Alva TT V2 are a high-output moving-coil cartridge, which is premounted in a headshell, a 1m (39″) RCA stereo interconnect cable plus a grounding wire (not used if the built-in phono stage is engaged), a smoked dustcover with hinges, and an Ortofon stylus pressure gauge. The cartridge has an elliptical stylus and aluminum cantilever; its specified frequency response is 30Hz–20kHz, ±1dB. The RIAA accuracy of the Alva’s phono stage is specified at ±0.3dB from 30Hz to 20kHz.

Setup

The Alva TT V2 comes with an illustrated Quick Start Guide that provides basic setup instructions. A full manual is available on Cambridge Audio’s website.

For my first round of listening, I placed the Alva on a coffee table near the primary speaker of the LS60 Wireless. The floor in our living room (and hence, the top surface of that coffee table) is level, which obviated the need to level the turntable. That was a good thing because the Alva does not have adjustable isolation feet. It sits on a long strip of rubberized plastic across the front and two narrow strips on the back. If the surface had not been level, I would have to place some kind of shim under one of these strips.

Following the instructions in the Quick Start Guide, I lowered the platter onto the spindle, screwed the counterweight into the back of the tonearm, screwed the headshell with its premounted cartridge into the front of the ’arm, and removed the stylus guard. I was glad to be spared the onus of mounting the cartridge in the headshell; it is a fiddly process. The counterweight does not have markings for stylus pressure. To set the tracking force, you adjust the counterweight so there is some downward force, lower the stylus onto the 2g marking on the Ortofon gauge (2g is the recommended tracking force for the supplied cartridge), and adjust the counterweight until the gauge is level. It’s tricky but doable. Next, I set the rotary antiskate dial to 2, matching the tracking force. Finally, I inserted the dustcover hinges into the receptacles and fastened the cover, set the Output Level switch to Line to engage the phono stage, and connected the RCA cable to the turntable and the primary speaker’s analog inputs. One minor nit: the supplied cable is fine if you’re connecting the turntable to a preamp or an integrated amp—you do want to keep it short. But if you’re connecting it to an active or a powered speaker, it’s a bit short.

Before spinning any vinyl, I turned the LS60 system’s volume to a high but comfortable level and selected the analog input. With the platter spinning but the cue lever raised and my ear a foot away from the UniQ driver in the right channel, I could hear no noise. This is a quiet phono stage. Cambridge Audio specifies its signal-to-noise ratio at >90dB, and I find that claim believable.

I then turned on Bluetooth and tried to pair the Alva with my KEF speaker system. At first, pairing failed, but only because the KEF was already paired with my phone. Once unpaired from the phone, the KEF paired with the turntable without a hitch. On a few other occasions, I had to repeat the pairing process. But I can’t fault Cambridge here; mild frustrations are not uncommon with Bluetooth.

All told, unpacking and setup took just over half an hour. It was time now to spin some records.

Listening

I started with one of my memento purchases, the 50th anniversary reissue of David Crosby’s 1971 album If I Could Only Remember My Name (Atlantic RR1 7203 603447543411). On “What Are Their Names,” the Cambridge turntable and cartridge uncovered all the nuances in the guitar work of Crosby, Jerry Garcia, and Neil Young, whose instruments were arrayed across the front of the soundstage. I could hear the action of the picks against the strings and sense the varied pressure they used to create each note and phrase. The leading edges of Phil Lesh’s notes on bass guitar and Michael Shrieve’s beats on the snare and kick drums had just the right degree of speed and impact. On “What Are Their Names,” Crosby, Garcia, Young, Graham Nash, Joni Mitchell, David Freiberg, Paul Kantner, and Grace Slick all sing in harmony. The Alva-LS60 combo tracked their expressive singing beautifully, highlighting their individual contributions to the mix. It created a wide, deep soundstage throughout, with Shrieve’s drums at the back, the singers gathered at the front, and the guitarists off to the sides.

Streamed via Bluetooth, the sound was more closed-in and homogenized, and the soundstage more two-dimensional—it lacked depth. The touch of the guitarists was resolved a tad less clearly, transients were slightly blurred. Shrieve’s snare drum had a little less texture, and the singers’ voices weren’t separated as clearly. Don’t get me wrong—I enjoyed what I heard. But given a choice, I’d use a wired connection.

Diving into my late parents’ record collection, I found Otto Klemperer’s iconic recording of Johannes Brahms’s A German Requiem, with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Chorus (Angel SB-3838-2 SQ-1-37258). This double album is in excellent shape, but the odd layout of the piece on the two records in the set shows its age: sides 1 and 4 are on one disc, sides 2 and 3 on the other—this album was sequenced for playback on record changers!

Again, I started with an RCA connection. The second movement, “Den alles Fleisch es ist wie Gras” (For all flesh is like grass), alternates between terror and serenity before closing with a transcendent passage promising salvation. The sound was wonderfully spacious throughout, with transparent orchestral and choral textures, excellent front-to-back layering, and thrilling dynamics. Even in the densest passages, the chorus and orchestra remained distinct and easy to follow, as was the text. The timpani beating out the mournful march rhythm had wonderful palpability. When the chorus belts out the first repeat of the opening passage, there was no hint of congestion or hardness. String tone was lush but with excellent detail. I could hear the action of the bows on the strings; there was no raspiness.

This pressing is at least 40 years old, and it has a few scratches. When played on the Alva, these momentary disturbances did not call much attention to their presence and did not detract from my enjoyment of the music. I heard no cartridge mistracking during the concluding part, even though it’s the last track on the side.

When I switched from the line-level output to Bluetooth, the presentation became more homogenized. Orchestral and choral textures were a little less transparent, and the sound of the violins was slightly truncated. Loud sections were a tad more congested and dynamics a bit more compressed. The soundstage was not as deep, but deep enough to sustain the realism of the presentation. I wouldn’t hesitate to use Bluetooth if this were the only way I could play vinyl on my system.

A noteworthy limitation of the Alva-LS60 pairing is that while the Alva supports the SBC Bluetooth codec as well as the higher-resolution aptX and aptX HD, the LS60 supports only the SBC and AAC codecs. When I was streaming to the LS60 via Bluetooth, the Alva was using SBC (as confirmed by the solid blue LED on the rear panel).

I did most of my listening with the turntable very close to the primary speaker to ensure fair comparison of Bluetooth and hardwired operation. But as an experiment, I moved the turntable upstairs, to my home office. It communicated reliably with the KEF system a floor below without interruption.

The LS60 Wireless doesn’t have a phono stage, so with the wired connection, I was using the phono stage built into the Alva turntable. For my next round of listening, I connected the turntable (phono stage still engaged) to the phono input of Klipsch’s The Nines active speaker system ($1499, review pending). I placed the Klipsch speakers on 28″ sand-filled speaker stands on either side of the fireplace in the living room, where the LS60 Wireless speakers normally stand, and played Cécile McLorin Salvant’s cover of Sting’s “Until,” from her album Ghost Song (Nonesuch 075597914665). This is the last track on side A, and the Alva tracked it flawlessly. I noticed the same absence of noise I had experienced with the LS60 Wireless. With my ear 6″ from the left-channel tweeter, I could hear very mild hiss; farther away, it was inaudible.

When I deactivated the phono stage on the turntable and engaged the one in the Klipsch system, I could hear mild hum and hiss from my listening position, 7′ away, with no music playing and the volume set at a comfortable listening level. That was no surprise. The higher-voltage line-level output is less susceptible to induced noise than the low-voltage phono output.

The spatial presentation was more two-dimensional using the Klipsch phono stage; everything was on the same plane as the speakers. Not only was the soundstage deeper with the Alva phono stage, but also imaging was more precise. Sullivan Fortner’s piano touch had clearer micro detail with the Alva’s phono stage, and Keita Ogawa’s kick drum had a more palpable punch. Transients on the banjo were faster and segued more convincingly into the twangy resonance of the soundbox. With the Klipsch phono stage, everything was mushed together. The difference was not subtle.

I repeated the test, with the same track, on the Q Acoustics Q Active 200 system in my home office. The differences weren’t quite as dramatic as with the Klipsch system, but they were definitely audible. Dynamics were more effortless using the phono stage in the Alva, more compressed on the Q system’s phono stage. There was more space around the instruments and vocals with the Alva handling phono preamplification and RIAA equalization.

There’s another compelling use case for the Alva TT V2: streaming music to Bluetooth headphones. I paired a set of PSB M4U 8 MKII noise-canceling headphones ($399) with the turntable. Again, with the cue lever raised and headphones’ volume control set at a comfortably high level, I heard no noise with no music playing. The Bluetooth LED on the back panel blinked periodically, confirming that a high-precision codec (most likely aptX HD) was in use.

I plunked one of the first albums I bought after I started with the SoundStage! Network onto the turntable: Chris Thile & Brad Mehldau (Nonesuch 558062-1), the excellent collaboration between the bluegrass singer and mandolinist and the jazz pianist. Their cover of Joni Mitchell’s “Marcie” sounded gorgeous. I could hear every nuance in Thile’s word-painting of this lovely song and every subtle variation in his strumming. Every note, every chord was beautifully delineated. Mehldau’s piano was just as transparent: clear transients, lovely sustains, delicate decays.

I found it liberating to listen to vinyl untethered. But there was a limit to how far I could be from the turntable. Bluetooth connection got disrupted if I walked away, even into an adjacent room, and a nasty zap resounded through the headphones. Given the distance over which the Alva could communicate with the KEF speakers, this limitation is most likely that of the PSB cans, not the turntable.

Conclusion

An occupational hazard of reviewing audio gear is the temptation to acquire components that have been a joy to audition. I experienced that itch with the Alva TT V2 but managed to resist scratching it. If there had been a convenient location for the turntable near the primary KEF speaker, or if the KEF supported the premium aptX HD codec—who knows?

The Alva TT V2’s built-in phono stage and Bluetooth transmitter make it possible to add vinyl playback to lifestyle music systems like the LS60 Wireless and to listen to vinyl through headphones. But this is a much more serious record player than typical Bluetooth ’tables. With its attractive styling, robust build, and excellent performance, Cambridge Audio’s Alva TT V2 seems tailor-made for serious Simplifi’d hi-fi.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse

Associated Equipment

- Active loudspeakers: KEF LS60 Wireless, Klipsch The Nines, Q Acoustics Q Active 200.

- Headphones: PSB M4U 8 MKII.

Cambridge Audio Alva TT V2 Turntable

Price: $1999.

Warranty: One year, parts and labor.

Cambridge Audio

1913 N. Milwaukee Ave

Chicago, IL 60647

Email:

Website: www.cambridgeaudio.com