Can an audio component be more than the sum of its parts? Bryston’s new BDA-3.14 streaming DAC-preamp ($4195, all prices USD) invites that question. Essentially, it combines two products on one chassis: the acclaimed BDA-3 DAC ($3795) and a network streamer based on the BDP-Pi ($1495). The BDP-Pi derives its name from the Raspberry Pi single-board computer at its core. Hence the model number of the new integrated product -- 3.14 is an approximation of the mathematical constant pi (π), denoting the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter.

Like the BDA-3, the BDA-3.14 has a full range of digital inputs, plus balanced and single-ended analog outputs. Like the BDP-Pi, it has an Ethernet port, USB Type-A ports for connecting external drives, and built-in clients for the Qobuz and Tidal streaming services. Roon Ready, it can act as a Roon endpoint; and its AirPlay emulator allows it to accept CD-resolution streams from i-devices, Macs, and iTunes libraries on Windows PCs. The BDA-3.14’s digital volume control lets it be used as a preamp.

That combination of features makes the BDA-3.14 ideal for Simplifi’d hi-fi. Connect it to a set of active speakers (e.g., my own Elac Navis ARF-51s, $4599.96/pair), and you have a complete high-performance digital music system. Of course, you can also use the BDA-3.14 with a power amp and conventional passive speakers, and use it as a preamp and digital source -- or bypass its volume control and connect it to a preamp or integrated amp and use it as a DAC.

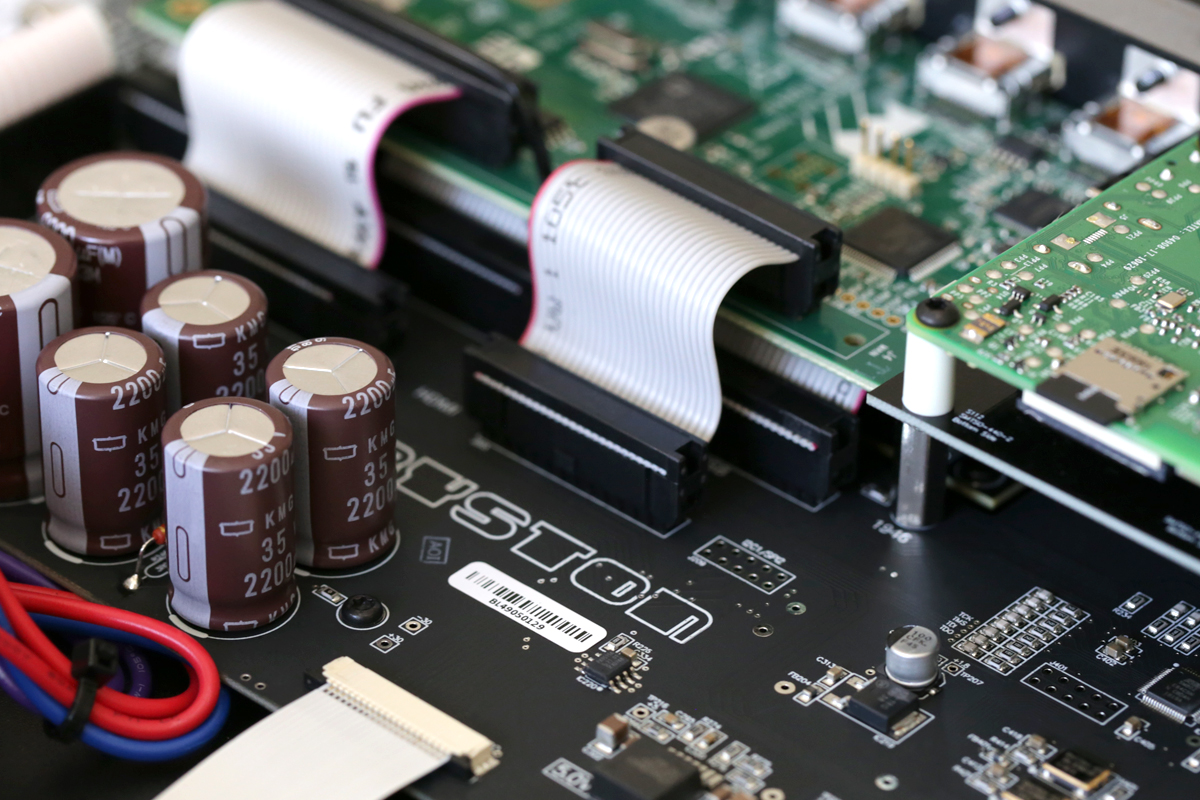

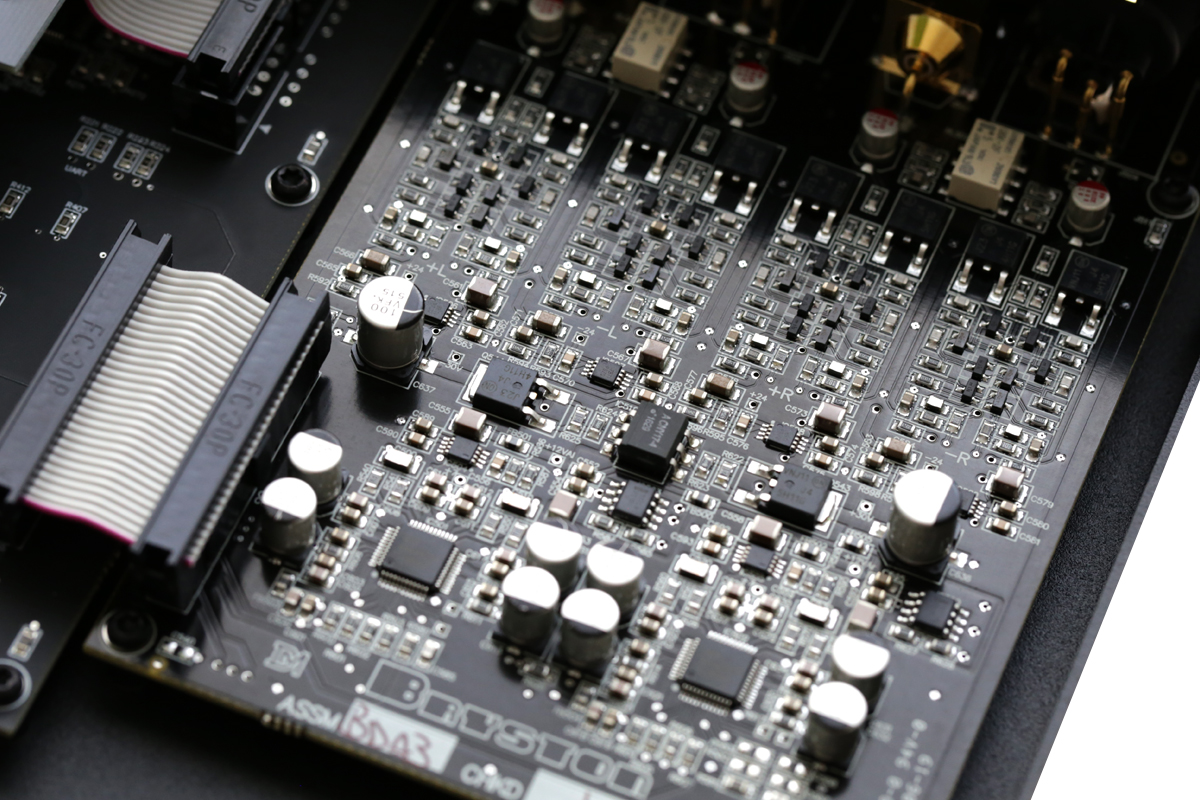

Inside and out

Weighing 8.45 pounds and measuring 17”W x 3.4”H x 12”D, the BDA-3.14 has the same outer dimensions as the BDA-3. (Both models are also available with 19”W faceplates.) Build quality is typical Bryston -- exemplary -- with an aluminum case and a beautiful, tastefully understated faceplate of anodized aluminum available in black or silver.

The BDA-3.14’s front panel looks almost identical to the BDA-3’s. At far right is a standby/on switch, and to its left are ten pushbuttons for selecting sources, and an 11th for selecting the upsampling function. Upsampling is available with AES/EBU and all S/PDIF inputs, but not with the USB or streaming inputs. Above each button is an LED that lights up to indicate that that source has been selected. To the left of that array are three columns of four LEDs each, these indicating the sampling rate of the digital signal and confirming that the DAC has locked on to the digital source.

That leftmost source button, Optical/Streaming, toggles between the optical input and the built-in streamer. The LEDs above the source buttons also function as volume indicators whenever the volume is adjusted, either with the remote, via Roon, or via the streamer’s web interface. Besides adjusting volume and muting sound, the remote lets you select among the ten inputs, and can be used to operate Bryston CD players, integrated amplifiers, and preamplifiers.

While the BDA-3.14’s manual has an abundance of technical detail, there’s no information at all about the remote -- not the buttons’ functions (which are fairly obvious), or even how to replace its batteries (which isn’t at all obvious). After a few days of use, the AAA batteries in my review sample’s remote died. To replace them, I had to remove the remote’s top and bottom covers using a 1.5mm hex key, then push the circuit board out through the bottom to access the battery compartment. With no guidance from the manual, I had to figure this out for myself.

On the rear panel are all the input and output jacks found on the BDA-3. The inputs are two USB Type-B ports for connection to a computer, one BNC and one coaxial S/PDIF (RCA), one TosLink S/PDIF, one AES/EBU balanced digital, and four HDMI 1.4a. The outputs are one set each of single-ended (RCA) and balanced (XLR) analog, and an HDMI 1.4.

As with the BDA-3, the HDMI ports allow the BDA-3.14 to accept signals from video sources such as media adapters and BD players, and to pass through video to an attached display at resolutions of up to 4K at 30fps. The BDA-3 and BDA-3.14 don’t support HDMI-ARC (Audio Return Channel), and so can’t receive audio from the connected display.

The HDMI port can also be used for playback of SACDs from universal players. Via HDMI, the BDA-3.14 and BDA-3 can accept PCM audio to 24-bit/192kHz and DSD64, but neither supports surround codecs. Via AES/EBU and coaxial S/PDIF, the maximum resolution is 24/192 PCM and 24/96 via TosLink. From the asynchronous USB Type-B ports, the maximum resolutions are 32/384 PCM and DSD256.

The rear panels of the BDA-3 and BDA-3.14 have RS-232, USB, and SMC-Ethernet interfaces for integration into home-automation systems. There’s also a 3.5mm trigger input for toggling between power and standby from a master component.

High and just left of center on the BDA-3.14’s rear panel are five ports that are also present on the BDP-Pi: four USB Type-A ports (labeled USB Accessory) and an Ethernet networking port.

Like the BDP-Pi, the BDA-3.14 lacks built-in Wi-Fi. If your network router is in a different room from your audio system, you can connect a Wi-Fi dongle to one of its USB Accessory ports. If you go that route, the BDA-3.14 will create a Wi-Fi hotspot. As documented in the manual, you use your smart device’s Wi-Fi Settings function to connect to the hotspot network; then, in the screens that follow, you configure the BDA-3.14 to connect to your network. Or you can do as I did: Connect a Wi-Fi access point to the BDA-3.14’s Ethernet port, in which case no configuration is necessary.

You can also connect USB drives to the BDA-3.14’s USB Accessory ports, and select music from a web browser on a smart device, tablet, or computer. (I describe the BDA-3.14’s browser interface in greater detail below, in Setup and Software.)

Data from drives connected to the USB Accessory ports go through the BDA-3.14’s Raspberry Pi-based streamer, whose maximum resolution is 24/192 PCM. The streamer module can play DSD files stored on an external or network drive, but these are resampled to 24/192 PCM before being passed on to the DAC. However, the BDA-3.14 will not play DSD via Roon.

The BDA-3.14’s streamer section sends PCM data to the DAC section via an Inter-IC Sound (I2S) interface. Because I2S uses separate lines for the clock and PCM data, the interface is inherently jitter-proof. With S/PDIF and USB, the clock signal must be recovered from the datastream. In that sense, the BDA-3.14 is more than the sum of its parts -- its integrated design permits use of the I2S interface rather than USB or S/PDIF, the latter typically used to connect a streamer to a DAC -- e.g., a BDP-Pi to a BDA-3.

Other refinements include separate power supplies for the digital and analog sections, and a fully balanced, class-A output stage.

Setup and software

My review sample of the BDA-3.14 arrived on March 13, the day before Pi Day (3/14). I connected its balanced outputs to the balanced inputs of my Elac Navis ARF-51 analog active speakers with a 2m-long pair of Argentum Acoustics Mythos balanced interconnects (XLR). I also attached a 500GB Samsung SSD to one of the BDA-3.14’s USB Accessory ports. And because the BDA-3.14 lacks built-in Wi-Fi, I ran a 1m network cable from a Google Wifi access point to the BDA-3.14’s Ethernet input.

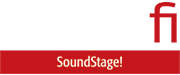

No app is available -- or needed -- to use the BDA-3.14’s streaming capabilities. Instead, the BDA-3.14 serves up a web user interface that Bryston playfully calls Manic Moose. (Well, they are, like me, Canadian.) To access the interface, type my.bryston.com into the address line of any web browser on a smartphone, tablet, PC, or Mac. Up will come a webpage showing all the Bryston components on your home network -- choose the BDP-3.14, and you’ll see the player’s Dashboard.

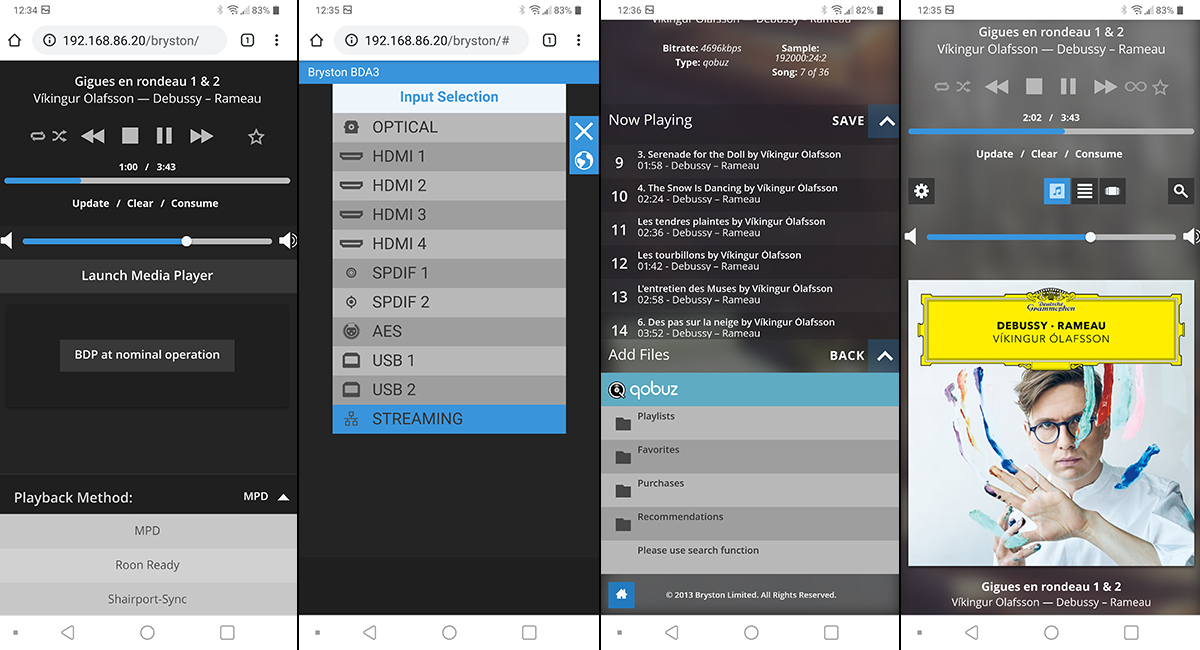

The BDA-3.14 serves up a mobile version of the interface for smartphones, and a desktop version for PCs, Macs, and tablets. Tablet users should keep their device in horizontal orientation, to keep the view less cluttered. iPhone and iPad users can add a link to the BDA-3.14’s interface to their device’s home screen by tapping the Sharing icon at the top right of the Safari browser screen and choosing the Add to Home Screen option. And, of course, you can create a bookmark for Manic Moose in any web browser.

At the top of the Manic Moose Dashboard are a volume-control slider, and transport controls for playing music in the current queue. Lower on the screen is the Playback Method button, which calls up a drop-down menu with three streaming options: MPD, for using the Media Player app that’s part of the Manic Moose UI; Roon Ready, for using the BDP-3.14 as a Roon endpoint; and Shairport Sync, for streaming to the BDA-3.14 via AirPlay. An option labeled Bradio is used for selecting the BDP-3.14’s Internet Radio function.

The Settings menu at the bottom of the Dashboard has some useful functions. Audio Devices can be used to set the default startup volume: Choose 0dB if you’re connecting the BDA-3.14 to an integrated amplifier or preamp and want fixed-level output; -60dB is the default level. Use NAS Setup to enable Manic Moose’s Media Player to stream music from a NAS system on your home network. And Update Firmware is worth checking periodically.

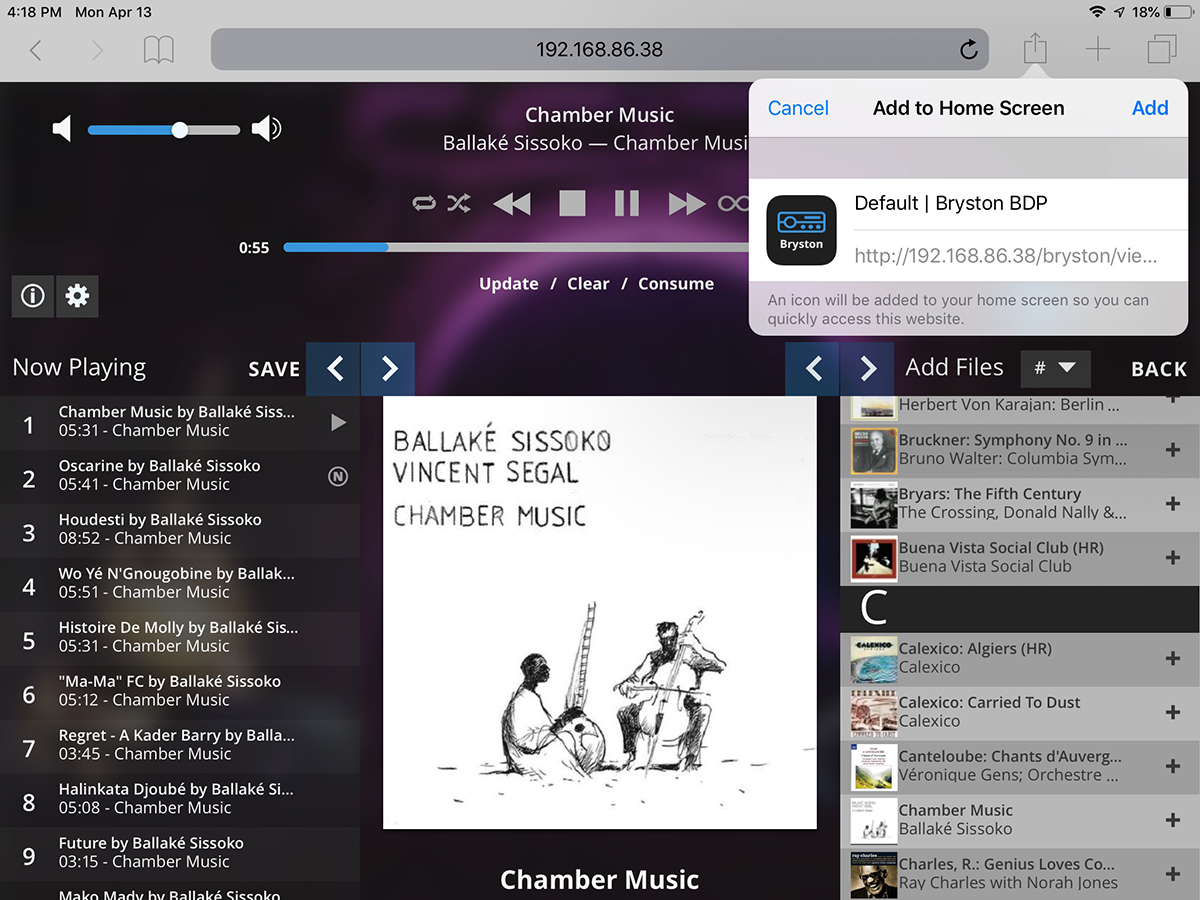

In the top right corner of the Dashboard is the Media Player button. Media Player also has volume and transport controls at the top. An Add Files pane lets you view the contents of USB and network drives by Drive Name, Folder, Genre, Artist, Album, Playlist, and other parameters; at the bottom of this pane are buttons for Tidal, Qobuz, and Internet Radio. The first time you choose Tidal or Qobuz, you’ll be prompted to enter your username and password -- after that, you’ll see a menu where you can choose content from your selected service. To add a playlist, album, or track to the play queue, just click the + sign next to your selection. You can tap an album or playlist to see its contents, then add individual tracks to the queue. When you’re done, you use the transport controls at the top of the screen to initiate playback and navigate the queue.

While the Manic Moose interface lacks visual polish, it’s functionally rich and operationally solid. The learning curve was gentle -- it didn’t take at all long for me to figure out my way around.

As is typical with network entertainment, I experienced a few hiccups. Very occasionally, when playing music from the Samsung SSD attached to one of the BDA-3.14’s USB Accessory ports, playback would stop for no apparent reason, and the player would lock up. To restore normal operation, I had to turn it off and back on again.

If I disconnected the BDA-3.14 from the wall outlet, on reconnection it would have a new IP address on my home network. This meant that the link on my iPad Mini’s home screen wouldn’t connect to the BDA-3.14, because it was searching for the Bryston on an old IP address. Similarly, browser bookmarks would no longer link to the BDA-3.14. I had to enter my.bryston.com in the address line of a web browser to find the BDA-3.14 at its new IP address and, if desired, create a new bookmark and/or a link on my iPad’s home screen.

With some operations, I found the BDA-3.14’s streamer very slow. If it went into standby with the Streaming input engaged, it took 1:40 to boot up when I turned it back on.

While the Media Player was responsive when playing music from an attached SSD drive, it was slower when using Tidal or Qobuz. It typically took 30 seconds for my Qobuz favorite albums to load, and about 10 seconds for Tidal favorite albums. If you’re checking out the tracks on one of your favorite Tidal or Qobuz albums and want to go back to the list of Favorite Albums, that list has to load all over again -- with Qobuz, another 30-second wait. That can be pretty tedious if you want to add to your playback queue tracks from a bunch of different albums. Bryston said it had not seen this problem on other units in the field, and wondered if my mesh network might be causing this slow response. That’s a possibility. However, my NAD C 658 streaming DAC-preamp, which is on the same network, and connected to the same access point, loads Tidal and Qobuz favorites much more quickly.

Listening

When I began listening to the Bryston BDA-3.14, my first thought was, “Wow, this sounds really nice.” Among its immediately obvious virtues was that it was extremely quiet -- at normal volume levels, with no music playing and my ear next to a tweeter, I heard only a very faint hiss. From a foot away, I heard nothing. And as soon as I began listening attentively, it was obvious that the BDA-3.14 had amazing dynamics and fluidity -- the combination drew me into the music in a way I’ve rarely experienced.

In his April 1 Opinion piece, “After 25 Years -- Is This the World’s Best Audio System?,” Doug Schneider talks about experiencing “more than a hint of synesthesia” while listening to Lana Del Rey’s Norman Fucking Rockwell! through “the best hi-fi system I’ve ever heard”:

[I]t was as if I were seeing only the recording in front of me -- and only the recording, not the speakers or amps or cables or anything else. The entire soundstage looked like a light-yellow haze that extended past the speakers’ outer side panels and a few feet behind their front baffles; and since I know what Del Rey looks like from photos, as the image of her voice hovered in air, an image of her face also appeared.

I can’t say that the BDA-3.14 created that kind of experience for me, but it did something similar. The Bryston made it incredibly easy for me to visualize performers playing the music I was hearing.

Using the Manic Moose media player, I streamed a new album of solo keyboard music by Debussy and Rameau, by the Icelandic pianist Víkingur Ólafsson (24-bit/192kHz FLAC, Deutsche Grammophon/Qobuz). I could see, in my mind’s eye, the exact weight Ólafsson gives each note, and the rapid motions of his fingers in runs and trills. Ólafsson’s evocative, rapid right-hand playing -- not quite staccato, but almost -- and resonantly pedaled left-hand chords in Debussy’s The Snow Is Dancing; his playful, harpsichord-like phrasing in Rameau’s The Cyclopes; and his tender legato touch in Rameau’s The Arts and the Hours -- all were beautifully illuminated without ever sounding etched or spotlit. The BDA-3.14 showed off every aspect of Ólafsson’s pianism -- not just its dynamic expression, but its tonal colors as well. I felt that these elements would not have been clearer to me had I been watching a video performance of Ólafsson performing these works. None of these details jumped out to commandeer my attention -- they were just there, integral parts of a wonderful musical experience.

Equally impressive was how the BDA-3.14 presented the decays of Ólafsson’s Steinway into a deliciously resonant acoustic, and how the sound seemed completely divorced from the speakers.

(An interesting and coincidental side note: Discussing the album’s cover photo, shot through a pane of glass on which Ólafsson is finger painting streaks of various hue, he said, in an interview on National Public Radio, “I do have this condition called synesthesia, where I associate different pitches with different colors. The pitch of C, the middle C on a piano for instance, would be white for me. One white key above would be the D pitch, which would be brown. The E pitch is green, F pitch is blue, and then G is red and A is yellow, et cetera.”)

Played via Manic Moose’s Media Player from the Samsung SSD attached to one of the BDA-3.14’s USB ports, “Le Mal de Vivre,” from Cécile McLorin Salvant’s For One to Love (24/88.2 FLAC, Mack Avenue), proved to me that the BDA-3.14 was just as impressive at reproducing the human voice. It nailed Salvant’s whispery delivery at the beginning of this lovely song by Monique Andrée Serf. In such words as vivre and rien, it was obvious (but not too obvious) that Salvant’s Gallic r’s were being formed at the very back of her tongue, just in front of her throat. Her b’s and p’s were just as plainly formed by her lips. These details were perfectly accented -- b’s and p’s never sounded spitty. When she sang slightly louder to make a musical-emotional point, the BDA-3.14 tracked those dynamic nuances beautifully. Again, the perfection with which these details were presented made it easy to visualize Salvant singing on a stage, standing just to right of center and a couple of feet behind the plane described by the speakers’ baffles. In my mind’s eye, I could see how she shaped each word and phrase.

The instrumental accompaniment was just as satisfying. As with the Víkingur Ólafsson album, I could visualize the precise weight pianist Aaron Diehl gave each note and chord. Lawrence Leathers’s skittering brushed snare drum and quiet kick drum were just as convincing -- no in-your-face spotlighting, just exquisite detail at the service of the music.

To check out how the BDA-3.14’s streamer handles DSD files, I played an SACD rip of Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon (DSD64, Harvest), which I’d loaded onto the Samsung SSD. The BDA-3.14’s Pi-based streamer resampled the DSD bitstream to 24/192 PCM.

It sounded glorious. The sound effects in “Speak to Me” -- the pulsing heartbeat, the ringing alarm clocks, the cash registers, the maniacal laughter, the threatening machinery -- appeared from all over the soundstage, well beyond the speaker plane, as if emerging from the ether. In the instrumental intro to “Breathe,” the music had an easy flow that picked me up and carried me in its wake. Nick Mason’s kick drum and floor tom had marvelous body and palpability, and David Gilmour’s singing sounded excellent -- consonants were intelligible, but again, not the least bit over-etched.

In “Money,” the sound effects were fast and snappy but not harsh. Gilmour’s lead guitar on the left had superb crunch; and Dick Parry’s tenor sax in the center just wailed. I loved how the BDA-3.14 presented this dense mix -- it sounded simultaneously complex and transparent.

As good as this classic album sounded through the BDA-3.14’s streamer, it sounded even better in native DSD64, played via Audirvana Plus 3.2.19 on my MacBook Pro, which I’d connected to the BDA-3.14’s USB 1 input with a 2m AudioQuest Cinnamon link.

In “Money,” Roger Waters’s bass-guitar riffs had more snap and impact, Gilmour’s lead guitar and Parry’s sax more bite, and Richard Wright’s Wurlitzer piano a bit more harmonic richness. Gilmour’s voice sounded just a bit more embodied, and the cash-register sounds were better articulated. Overall, the sound was smoother -- by comparison, there was a bit of glare in the resampled version the streamer module was playing from the SSD. The difference was nowhere near night-and-day -- the 24/192 resampled stream from the Pi module sounded excellent -- but I preferred the native DSD version the BDA-3.14 presented via USB.

Wanting to hear how the streamer would compare with the USB input on a PCM album, I set the BDA-3.14’s streamer to Roon Ready mode, then, in the Roon app on my MacBook Pro and using the BDA-3.14’s streamer input as the endpoint, cued up Gil Shahan’s 1995 recording of Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No.1, with the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by André Previn (16/44.1 ALAC, Deutsche Grammophon). The first movement oscillates between fairytale dreaminess and spiky irony. A minute in, Shahan begins playing the nostalgic waltz theme, which steadily grows in intensity -- I could visualize him swaying as he expressed more feeling through his violin. Was he actually doing that when this performance was recorded? There’s no way to know, of course, but that was the picture the BDA-3.14 presented. In the faster, spikier passages later in the movement, I could visualize the movement of his bow on the strings, and the exact amount of pressure he applied -- and I’d bet dollars to doughnuts that my mind’s eye was not in the least deceiving me. His violin tone was consistently gorgeous -- ringing, but not steely in the upper strings, and with beautifully woody body in pizzicato passages.

Switching to the MacBook Pro and the BDA-3.14’s USB 1 input, I at first thought that Shahan’s violin sounded a little bit less steely -- but then I went back to the streamer and concluded that that sounded smoother. Bottom line: If there were sonic differences (which I doubt), they were small to the point of insignificance.

To check out the BDA-3.14’s HDMI features, I connected my Samsung UMB-M7500 Ultra HD BD player to the HDMI 4 input, and its HDMI output to the HDMI 2 input on the One Connect Box for my Samsung 55” Frame TV, then loaded up the Ultra HD BD of The Fifth Element: 20th Anniversary Edition. The BDA-3.14 passed the 4K video through to my TV successfully, but did not deliver the HDR (high dynamic range) imagery on this disc, as HDR is not supported by HDMI 1.4.

The Dolby Atmos soundtrack, downmixed to two-channel stereo, sounded wonderful through the Elac Navis ARF-51 active floorstanders. The big chase scene in which the hero, ex-commando Korben Dallas (Bruce Willis), helps the heroine, Leeloo (Milla Jovovich), escape the authorities in his flying taxi, was gobs of fun. While the effects weren’t nearly as immersive as they would have been through a full surround array, they had loads of impact, and extended past the speaker plane.

Comparison

Like the BDA-3.14, iFi Audio’s Pro iDSD ($2749), which I reviewed in April 2020, has a built-in network streamer. As I noted in my review, I was bothered by some of the Pro iDSD’s operational quirks but loved the way it sounded. I liked the BDA-3.14 even more.

The Pro iDSD has tubed and solid-state output stages as well as a huge range of settings, and for this comparison I chose those that worked well for me during my review. For the Prokofiev recording, I set the Pro iDSD to solid-state mode, with its DSD512 Remastering and Gibbs Transient Optimized (GTO) filter selected. I found the overall sound of the iFi a bit more dramatic and exciting than the Bryston’s, but also less refined and revealing. The tone of Gil Shahan’s violin was a little steelier. Dynamics were more sudden and dramatic but not as finely graduated, which made it not quite as easy to visualize his bowing. I also found orchestral textures more transparent with the BDA-3.14.

For “Money,” from Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, I set the iDSD to No Upsampling, which meant I was listening in native DSD64, just as I was with the BDA-3.14. Through the Pro iDSD, Roger Waters’s bass guitar hit a little harder. But Dick Parry’s tenor sax didn’t have quite as much reedy bite, and David Gilmour’s lead guitar didn’t have quite as much crunch. Through the BDA-3.14 I was more aware of expressive details, such as Parry’s growling effects in his solo. The Bryston also threw a wider soundstage -- through the iDSD, the mix sounded a bit more closed-in.

We have to keep a few things in mind: The BDA-3.14 costs $1446 more than the Pro iDSD, and the iFi has features -- e.g., a headphone amplifier -- that the Bryston doesn’t. But the Bryston has a better streamer -- the Pro iDSD’s streamer is partially hobbled by poor software. And the BDA-3.14 has HDMI switching, which the Pro iDSD does not.

Conclusion

At the outset of this review, I rhetorically asked whether a component such as Bryston’s BDA-3.14 could be more than the sum of its parts. I think the answer is yes. Bryston’s BDA-3 DAC has received many glowing reviews, including one on SoundStage! Hi-Fi by Philip Beaudette, in July 2016. The BDA-3.14 costs only $400 more but adds a very capable streamer, based on a model that costs $1495 when purchased separately. Price-wise, the BDA-3.14 is very much less than the sum of its parts -- which is very welcome news.

I have a couple of concerns about the BDA-3.14. Not everyone will want to use its HDMI switching functions, but those who do may be concerned by the fact that the HDMI board is based on the old HDMI 1.4 standard -- which means no support for Audio Return Channel (ARC). And while the BDA-3.14 will pass through 4K video, it will not pass through the extra bits required for HDR images. However, Bryston says it’s working on integrating a more up-to-date HDMI module for the BDA-3.14 that will support HDR and possibly ARC. Existing units will be upgradable, the company adds.

I’ve also raised some issues about software and responsiveness. While somewhat workmanlike, the Manic Moose software is generally very solid -- and many listeners will find it completely satisfactory. Music lovers who want a richer, more responsive interface can splurge on Roon. Think of it this way: The combined price for a BDA-3.14 and a lifetime subscription to Roon is still $396 lower than the cost of buying a BDA-3 and BDP-Pi separately.

Sonically though, I have no reservations about the BDA-3.14. Quite the contrary -- I loved every moment I spent listening to it. The more I listened, the more the BDA-3.14 grew on me. It was still growing on me when I disconnected it from my system to pack it up and return it to Bryston.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse

Associated Equipment

- Active loudspeakers -- Elac Navis ARF-51

- Sources -- Apple MacBook Pro running Audirvana Plus 3.2.19 and Roon Bridge 1.7; Apple Mac Mini running Roon Core 1.7; Samsung 500GB SSD solid-state drive with an assortment of CD-resolution, hi-rez PCM and DSD albums; Samsung UMB-M7500 Ultra HD BD player

- Control devices -- Apple: iPad Mini 3, MacBook Pro, iPhone SE smartphone; LG G7 ThinQ smartphone

- Streaming DAC-preamplifier -- iFi Audio Pro iDSD 4.4

- Interconnects -- Argentum Acoustics Mythos, balanced (2m, XLR)

- USB link -- AudioQuest Cinnamon (2m)

- Network -- Google Wifi three-node mesh

- Display -- Samsung UN55LS003 55” The Frame UHD TV

Bryston BDA-3.14 Streaming DAC-Preamplifier

Price: $4195 USD.

Warranty: Five years parts and labor.

Bryston Ltd.

677 Neal Drive

Peterborough, Ontario K9J 6X7

Canada

Phone: (800) 632-8217, (705) 742-5325

Fax: (705) 742-0882

Website: www.bryston.com